eBook - ePub

Black American Biographies

The Journey of Achievement

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Black American Biographies

The Journey of Achievement

About this book

From the abolitionists and civil rights leaders who struggled to secure basic freedoms to the scientists, entertainers, and public servants who have nurtured innovation in their respective fields, African Americans have broken critical barriers for every American. This volume profiles many of those individuals—from Frederick Douglass to Oprah Winfrey to Barack Obama—whose efforts and ideas continue to enrich the foundations of the nation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black American Biographies by Britannica Educational Publishing, Jeff Wallenfeldt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Minority Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

ABOLITIONISM AND ACTIVISM

The African American struggle for freedom has had many faces and taken many forms. Often, in the beginning, it was a whisper, a secret lesson in reading and writing performed out of the sight of masters who forbade slave literacy, or it took the form of coded language—the forerunner of hip slang—that allowed slaves to communicate in the presence of unknowing slave owners. Before long it was a clarion call to action sounded with force and eloquence from the pulpit, the podium, the pavement, and in print. This chapter examines the lives and work of some of those who led the way toward fulfilling the promise the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States held for African Americans, keeping their eyes—and those of the people they led—on the prize of freedom and equality.

ABOLITIONISTS

One response to slavery was outright rebellion. Beginning early in the history of the republic, revolts led by slaves such as Gabriel and Nat Turner ultimately failed, but nevertheless shook the foundation of Southern society, prompting ever more repressive reactions by slave owners fearful that their way of life was threatened from inside and outside. Beyond the South the abolition movement gained force in the early 19th century, advanced partly by scores of sympathetic whites. Prominent among them were William Lloyd Garrison, who helped organize the American Anti-Slavery Society and was the publisher of the influential abolitionist periodical The Liberator; novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) opened the eyes of millions to the inhumanity of slavery; and John Brown, who led an assault by black and white abolitionists on the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Va. (now West Virginia), in 1859 in an attempt to spark a slave revolt, and whose biographer David S. Reynolds characterized as “the least racist white person” among those pre-Civil War figures he had investigated.

Notwithstanding the courage and commitment of these white fellow travelers, it was African American abolitionists who most forcefully and evocatively conveyed the urgency of the plight of their people, including David Walker, author of the incendiary pamphlet Appeal … to the Colored Citizens of the World … (1829); physician, army officer, and writer Martin R. Delany, whose righteous indignation was couched in an early form of black nationalism; and Frederick Douglass, the preeminent African American spokesman of his day, an organizer, journalist, and author who had the ear of Abraham Lincoln. Harriet Tubman not only provided an impassioned female voice but also risked her life again and again as a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

MARTIN R. DELANY

(b. May 6, 1812, Charles Town, Va., U.S.—d. Jan. 24, 1885, Xenia, Ohio)

Abolitionist, physician, and editor Martin Robison Delany espoused black nationalism and racial pride even before the Civil War period, anticipating expressions of such views a century later.

In search of quality education for their children, the Delanys moved to Pennsylvania when Martin was a child. At 19, while studying nights at an African American church, he worked days in Pittsburgh. Embarking on a course of militant opposition to slavery, he became involved in several racial improvement groups. Under the tutelage of two sympathetic physicians he achieved competence as a doctor’s assistant as well as in dental care, working in this capacity in the South and Southwest (1839).

Returning to Pittsburgh, Delany started a weekly newspaper, the Mystery, which publicized grievances of blacks in the United States and also championed women’s rights. The paper won an excellent reputation, and its articles were often reprinted in the white press. From 1846 to 1849 Delany worked in partnership with the abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass in Rochester, N.Y., where they published another weekly, the North Star. After three years Delany decided to pursue formal medical studies; he was one of the first blacks to be admitted to Harvard Medical School and became a leading Pittsburgh physician.

In the 1850s Delany developed an overriding interest in foreign colonization opportunities for African Americans, and in 1859–60 he led an exploration party to West Africa to investigate the Niger Delta as a location for settlement.

In protest against oppressive conditions in the United States, Delany moved in 1856 to Canada, where he continued his medical practice. At the beginning of the Civil War (1861–65) he returned to the United States and helped recruit troops for the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, for which he served as a surgeon. To counter a desperate Southern scheme to impress its slaves into the military forces late in the war, in February 1865, Delany was made a major (the first black man to receive a regular army commission) and was assigned to Hilton Head Island, S.C., to recruit and organize former slaves for the North. When peace came in April he became an official in the Freedmen’s Bureau, serving for the next two years.

In 1874 Delany ran unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor as an Independent Republican in South Carolina; thereafter his fortunes declined. He was the author of The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States Politically Considered (1852).

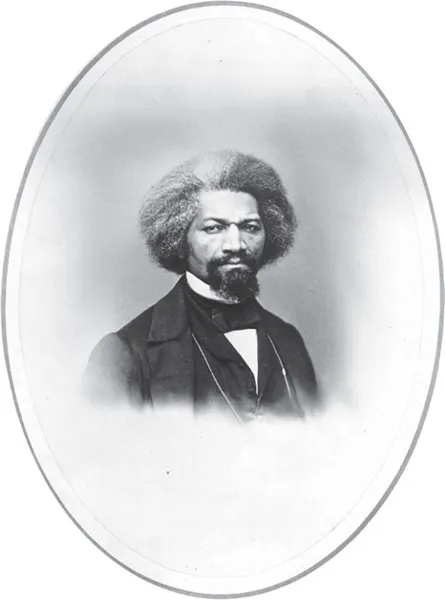

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

(b. February 1818?, Tuckahoe, Md., U.S.—d. Feb. 20, 1895, Washington, D.C.)

Frederick Douglass was one of the most eminent human-rights leaders of the 19th century. His oratorical and literary brilliance thrust him into the forefront of the U.S. abolition movement, and he became the first black citizen to hold high rank in the U.S. government.

Separated as an infant from his slave mother (he never knew his white father), Frederick (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey) lived with his grandmother on a Maryland plantation until, at age eight, his owner sent him to Baltimore to live as a house servant with the family of Hugh Auld, whose wife defied state law by teaching young Frederick to read. Auld, however, declared that learning would make him unfit for slavery, and Frederick was forced to continue his education surreptitiously with the aid of schoolboys in the street. Upon the death of his master, Frederick was returned to the plantation as a field hand at 16. Later, he was hired out in Baltimore as a ship caulker. Frederick tried to escape with three others in 1833, but the plot was discovered before they could get away. Five years later, however, he fled to New York City and then to New Bedford, Mass., where he worked as a labourer for three years, eluding slave hunters by changing his surname to Douglass.

At a Nantucket, Mass., antislavery convention in 1841, Douglass was invited to describe his feelings and experiences under slavery. These extemporaneous remarks were so poignant and naturally eloquent that he was unexpectedly catapulted into a new career as agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. From then on, despite heckling and mockery, insult, and violent personal attack, Douglass never flagged in his devotion to the abolitionist cause.

Frederick Douglass. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

To counter skeptics who doubted that such an articulate spokesman could ever have been a slave, Douglass felt compelled to write his autobiography in 1845, revised and completed in 1882 as Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Douglass’s account became a classic in American literature as well as a primary source about slavery from the bondsman’s viewpoint. To avoid recapture by his former owner, whose name and location he had given in the narrative, in 1845 Douglass left on a two-year speaking tour of Great Britain and Ireland. Abroad, Douglass helped to win many new friends for the abolition movement and to cement the bonds of humanitarian reform between the continents.

Douglass returned with funds to purchase his freedom and also to start his own antislavery newspaper, the North Star (later Frederick Douglass’s Paper), which he published from 1847 to 1860 in Rochester, N.Y. The abolition leader William Lloyd Garrison disagreed with the need for a separate, black-oriented press, and the two men broke over this issue as well as over Douglass’s support of political action to supplement moral suasion. Thus, after 1851 Douglass allied himself with the faction of the movement led by James G. Birney. He did not countenance violence, however, and specifically counseled against the raid on Harpers Ferry, Va. (October 1859).

During the Civil War (1861–65) Douglass became a consultant to Pres. Abraham Lincoln, advocating that former slaves be armed for the North and that the war be made a direct confrontation against slavery. Throughout Reconstruction (1865–77), Douglass fought for full civil rights for freedmen and vigorously supported the women’s rights movement.

After Reconstruction, Douglass served as assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), and in the District of Columbia he was marshal (1877–81) and recorder of deeds (1881–86); finally, he was appointed U.S. minister and consul general to Haiti (1889–91).

GABRIEL

(b. c. 1775, near Richmond, Va., U.S.—d. September 1800, Richmond)

Bondsman Gabriel Prosser, better known simply as Gabriel, planned the first major slave rebellion in U.S. history (Aug. 30, 1800). His abortive revolt greatly increased the whites’ fear of the slave population throughout the South.

The son of an African-born mother, Gabriel grew up as the slave of Thomas H. Prosser. Gabriel became a deeply religious man, strongly influenced by biblical example. In the spring and summer of 1800, he laid plans for a slave insurrection aimed at creating an independent black state in Virginia with himself as king. He planned a three-pronged attack on Richmond, Va., that would seize the arsenal, take the powder house, and kill all whites except Frenchmen, Methodists, and Quakers. Some historians believe that Gabriel’s army of 1,000 slaves (other estimates range from 2,000 to 50,000), assembled 6 miles (9.5 km) outside the city on the appointed night, might have succeeded had it not been for a violent rainstorm that washed out bridges and inundated roads. Before the rebel forces could be reassembled, Governor James Monroe, already informed of the plot, ordered out the state militia. Gabriel and about 34 of his companions were subsequently arrested, tried, and hanged.

HARRIET TUBMAN

(b. c. 1820, Dorchester county, Md., U.S.—d. March 10, 1913, Auburn, N.Y.)

Bondwoman Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery in the South to become a leading abolitionist before the Civil War. She led hundreds of bondsmen to freedom in the North along the route of the Underground Railroad—an elaborate secret network of safe houses organized for that purpose.

Born a slave, Araminta Ross later adopted her mother’s first name, Harriet. From early childhood she worked variously as a maid, a nurse, a field hand, a cook, and a woodcutter. About 1844 she married John Tubman, a free black.

In 1849, on the strength of rumours that she was about to be sold, Tubman fled to Philadelphia, leaving behind her husband, parents, and siblings. In December 1850 she made her way to Baltimore, Md., whence she led her sister and two children to freedom. That journey was the first of some 19 increasingly dangerous forays into Maryland in which, over the next decade, she conducted upward of 300 fugitive slaves along the Underground Railroad to Canada. By her extraordinary courage, ingenuity, persistence, and iron discipline, which she enforced upon her charges, Tubman became the railroad’s most famous conductor and was known as the “Moses of her people.” It has been said that she never lost a fugitive she was leading to freedom.

Rewards offered by slaveholders for Tubman’s capture eventually totaled $40,000. Abolitionists, however, celebrated her courage. John Brown, who consulted her about his own plans to organize an antislavery raid of a federal armoury in Harpers Ferry, Va. (now in West Virginia), referred to her as “General” Tubman. About 1858 she bought a small farm near Auburn, New York, where she placed her aged parents (she had brought them out of Maryland in June 1857), where she herself would come to live after the Civil War. From 1862 to 1865 she served as a scout, as well as nurse and laundress, for Union forces in South Carolina. For the Second Carolina Volunteers, under the command of Colonel James Montgomery, Tubman spied on Confederate territory. When she returned with information about the locations of warehouses and ammunition, Montgomery’s troops were able to make carefully planned attacks. For her wartime service Tubman was paid so little that she had to support herself by selling homemade baked goods.

Harriet Tubman, c. 1890. MPI/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

After the Civil War Tubman settled in Auburn and began taking in orphans and the elderly, a practice that eventuated in the Harriet Tubman Home for Indigent Aged Negroes. The home later attracted the support of former abolitionist comrades and of the citizens of Auburn, continuing in existence for some years after her death. In the late 1860s and again in the late 1890s Tubman applied for a federal pension for her Civil War services. Some 30 years after her service, a private bill providing for $20 monthly was passed by Congress.

NAT TURNER

(b. Oct. 2, 1800, Southampton county, Va., U.S.—d. Nov. 11, 1831, Jerusalem, Va.)

Bondsman Nat Turner led the only effective, sustained slave rebellion (August 1831) in U.S. history. Spreading terror throughout the white South, his action set off a new wave of oppressive legislation prohibiting the education, movement, and assembly of slaves and stiffened proslavery, antiabolitionist convictions that persisted in that region until the Civil War (1861–65).

Turner was born the property of a prosperous small-plantation owner in a remote area of Virginia. His mother was an African native who transmitted a passionate hatred of slavery to her son. He learned to read from one of his master’s sons, and he eagerly absorbed intensive religious training. In the early 1820s he was sold to a neighbouring farmer of small means. During the following decade Turner’s religious ardour tended to approach fanaticism, and he saw himself called upon by God to lead his people out of bondage. He began to exert a powerful influence on many of the nearby slaves, who called him “the Prophet.”

In 1831, shortly after he had been sold again—this time to a craftsman named Joseph Travis—a sign in the form of an eclipse of the Sun caused Turner to believe that the hour to strike was near. His plan was to capture the armoury at the county seat, Jerusalem, and, having gathered many recruits, to press on to the Dismal Swamp, 30 miles (48 km) to the east, where capture would be difficult. On the night of August 21, together with seven fellow slaves in whom he had put his trust, he launched a campaign of total annihilation, murdering Travis and his family in their sleep and then setting forth on a bloody march toward Jerusalem. In two days and nights about 60 white people were ruthlessly slain. Doomed from the start, Turner’s insurrection was handicapped by lack of discipline among his followers and by the fact that only 75 blacks rallied to his cause. Armed resistance from the local whites and the arrival of the state militia—a total force of 3,000 men—provided the final crushing blow. Only a few miles from the county seat the insurgents were dispersed and either killed or captured, and many innocent slaves were massacred in the hysteria that followed. Turner eluded his pursuers for six weeks but was...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Abolitionism and Activism

- Chapter 2: Protect and Serve

- Chapter 3: Exploration, Education, Experimentation, and Ecumenism

- Chapter 4: Arts and Letters

- Chapter 5: Stage and Screen

- Chapter 6: Music

- Chapter 7: Sports

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index