- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Carnivores

About this book

Sharp-toothed and quick-footed, carnivorous mammals are primed for the hunt. Far from ruthless, however, carnivores—hunters by nature and necessity—are integral to maintaining ecological balance. While predatory behavior often seems grisly, many carnivores are actually omnivorous and many can even be domesticated. This striking volume journeys from secluded forest habitats to our own homes to survey the unique features and behaviors of various species of carnivore. Vivid color photographs accompany the text and provide a detailed look at these amazing creatures.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

CARNIVORES

In a zoological sense, a carnivore is any member of the mammalian order Carnivora (literally, “flesh devourers” in Latin), comprising more than 270 species. In a more general sense, a carnivore is any animal (or plant) that eats other animals, as opposed to a herbivore, which eats plants. Although the species classified in this order are basically meat eaters, a substantial number of them, especially among bears and members of the raccoon family, also feed extensively on vegetation and are thus actually omnivorous.

Snow leopard (Panthera uncia). Russ Kinne/Comstock

The order Carnivora includes 12 families, 9 of which live on land: Canidae (dogs and related species), Felidae (cats), Ursidae (bears), Procyonidae (raccoons and related species), Mustelidae (weasels, badgers, otters, and related species), Mephitidae (skunks and stink badgers), Herpestidae (mongooses), Viverridae (civets, genets, and related species), and Hyaenidae (hyenas). There are three aquatic families: Otariidae (sea lions and fur seals), Phocidae (true, or earless, seals), and Odobenidae (the walrus). These aquatic families are referred to as pinnipeds.

IMPORTANCE OF CARNIVORA

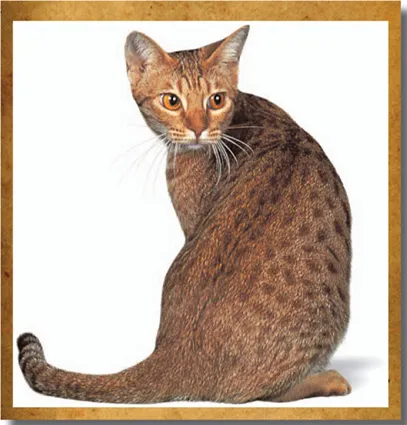

Two carnivores are probably the animals most familiar to people: the domestic dog and cat, both of which are derived from wild members of this order. On the other hand, various bears, felines, canines, and hyenas are among the few animals that occasionally attack humans. These large, dangerous carnivores are often the objects of hunters, who kill them for display as trophies. Most luxurious natural furs (ermine, mink, sable, and otter, among others) come from members of Carnivora, as do many of the animals that attract the largest crowds at circuses and zoos. Producers of livestock worldwide are concerned about possible depredations upon their herds and flocks by this group of mammals.

Being meat eaters, carnivores are at the top of the food chain and form the highest trophic level within ecosystems. As such, they are basic to maintaining the “balance of nature” within those systems. In areas of human settlement, this precarious balance has frequently been upset by the extermination of many carnivores formerly considered undesirable because of their predatory habits. Now, however, carnivores are recognized to be necessary elements in natural systems; they improve the stability of prey populations by keeping them within the carrying capacity of the food supply. As a result, the surviving animals are better fed and less subject to disease. Many of these predators dig dens and provide burrows in which other forms of wildlife can take refuge. Digging also results in the mixing of soils and the reduction of water runoff during rains. The carnivores best known for their burrow building are badgers and skunks, but bears, canines, and felines regularly engage in this behaviour as well.

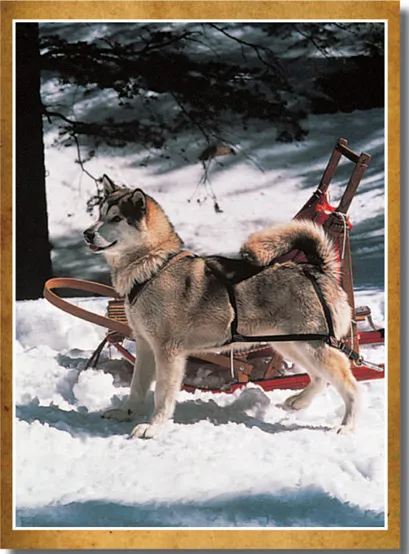

Alaskan Malamute. © Kent & Donna Dannen

Ocicat. © Chanan Photography

Carnivore numbers are limited by food, larger predators, or disease. When human influence removes larger predators, many of the smaller carnivores become extremely abundant, creating an ideal environment for the spread of infection. The disease of most concern to humans is rabies, which is transmitted in saliva via bites. Rabies is most common in the red fox, striped skunk, and raccoon, but it also occurs in African hunting dogs and can infect practically all carnivores. Billions of dollars are spent annually throughout the world to manage and control the incidence of this disease. In some countries, abundance of vector species, especially red foxes, is controlled by gathering the animals, or by dropping vaccine-laden bait from the air into their midst. In other countries, programs of “capture-vaccinate-release” are in place to reduce the vulnerability of individual animals. Other infectious diseases carried by carnivores and of concern to humans include canine distemper, parvovirus, toxoplasmosis, and leptospirosis.

Male lion (Panthera leo). R.I.M. Campbell/Bruce Coleman Ltd.

Striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis). E.R. Degginger

BEHAVIOUR

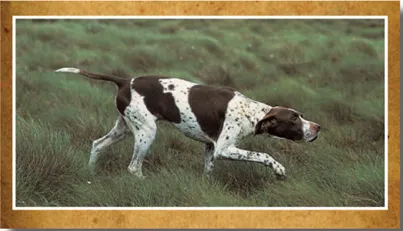

Carnivores rank high on the scale of intelligence among mammals. The brain is large in relation to the body, an indication of their superior mental powers. For this reason, these animals are among the easiest to train for entertainment purposes, as pets, or as hunting companions. The highly developed sense of smell among dogs, for instance, supplements the sharper vision of man. Dogs are the carnivores most commonly trained for hunting, but the cheetah, caracal, and ferret have also been used to some extent. In China the otter is trained to drive fish under a large net, which is then dropped and pulled in. Dependent for survival upon their ability to prey upon living animals in a variety of situations, carnivores have evolved a relatively high degree of learning ability.

Pointer on point. © Sally Anne Thompson/Animal Photography

Carnivorous mammals tend to establish territories, though omnivorous carnivores, such as the black bear, striped skunk, and raccoon, are less apt to do so. Territories are often exclusive, defended by the residents against other animals of their own kind. Such areas may sometimes be marked by secretions produced by anal or other scent glands and by deposition of feces in prominent locations.

There is a wide range of social patterns among carnivores. Many (bears, various foxes, genets, most cats, and most mustelids) are solitary except during the breeding season. Some remain paired throughout the year (black-backed jackal and lesser panda) or occasionally roam in pairs (gray fox, crab-eating fox, and kinkajou). Other carnivores, such as the wolf, African hunting dog, dhole, and coati, normally hunt in packs or bands. Various pinnipeds form sedentary colonies during the breeding season, sea otters congregate during a somewhat larger part of the year, and meerkats are permanently colonial.

Southern sea lions (Otaria byronia). George Holton/Photo Researchers

Mating systems vary among families, ranging from monogamy in the wolf and polygyny in most bears and mustelids to harems in elephant seals. Copulation is vigorous and frequent in many species, including the lion, and many species possess reproductive peculiarities as adaptations to their environments. Induced ovulation, for instance, allows females to release egg cells during or shortly after copulation. Delayed implantation of the fertilized egg in the wall of the uterus is another phenomenon that allows births to occur when resources are abundant. This phenomenon is most prominent in species living in highly seasonal environments. Delayed implantation is most extreme in the pinnipeds and bears but is absent from canines.

FORM AND FUNCTION

The smallest living member of Carnivora is the least weasel (Mustela nivalis), which weighs only 25 grams (0.9 ounce). The largest terrestrial form is the Kodiak bear (Ursus arctos middendorffi), an Alaskan grizzly bear that is even larger than the polar bear (Ursus maritimus). The largest aquatic form is the elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), which may weigh 3,700 kg (8,150 pounds). Most carnivores weigh between 4 and 8 kg (9 and 18 pounds).

The vast majority of species are terrestrial, but the pinnipeds are highly adapted to life in the water. Some nonpinnipeds, such as the sea otter, are almost fully aquatic, while others, such as the river otter and polar bear, are semiaquatic, spending most of their lives in or near water. Aquatic and semiaquatic forms have developed specializations such as streamlined bodies and webbed feet.

Carnivores, like other mammals, possess a number of different kinds of teeth: incisors in front, followed by canines, premolars, and molars in the rear. Most carnivores have carnassial, or shearing, teeth that function in slicing meat and cutting tough sinews. The carnassials are usually formed by the fourth upper premolar and the first lower molar, working one against the other with a scissorlike action. Cats, hyenas, and weasels, all highly carnivorous, have well-developed carnassials. Bears and procyonids (except the olingo), which tend to be omnivorous, and seals, which eat fish or marine invertebrates, have little or no modification of these teeth for shearing. The teeth behind the carnassials tend to be lost or reduced in size in highly carnivorous species. Most members of the order have six prominent incisors on both the upper and lower jaw, two canines on each jaw, six to eight premolars, and four molars above and four to six molars below. Incisors are adapted for nipping off flesh. The outermost incisors are usually larger than the inner ones. The strong canines are usually large, pointed, and adapted to aid in the stabbing of prey. The premolars always have sharply pointed cusps, and in some forms (e.g., seals) all the cheek teeth (premolars and molars) have this shape. Except for the carnassials, molars tend to be flat teeth utilized for crushing. Terrestrial carnivores that depend largely on meat tend to have fewer teeth (30 to 34), the flat molars having been lost. Omnivorous carnivores, such as raccoons and bears, have more teeth (40 to 42). Pinnipeds have fewer teeth than terrestrial carnivores. In addition, pinnipeds exhibit little stability in number of teeth; for example, a walrus may have from 18 to 24 teeth.

Several features of the skeleton are characteristic of the order Carnivora. Articulating surfaces (condyles) on the lower jaw form a half-cylindrical hinge that allows the jaw to move only in a vertical plane and with considerable strength. The clavicles (collarbones) are either reduced or absent entirely and, if present, are usually embedded in muscles without articulation with other bones. This allows for a greater flexibility in the shoulder area and prevents breakage of the clavicles when the animal springs on its prey.

The brain is large in relation to the weight of the body, and it contains complex convolutions characteristic of highly intelligent animals. The stomach is simple as opposed to multichambered, and a blind pouch (cecum) attached to the intestine is usually reduced or absent. Since animal tissues are in general simpler to digest than plant tissues, the carnivore’s dependence on a diet with a high proportion of meat has led to less-complex compartmentalization of the stomach and a decrease in the length and folding (and therefore surface area) of the intestine. The teats are located on the abdomen along two primitive lines (milk ridges), a characteristic of mammals that lie down when nursing.

Many carnivores have a well-developed penis bone, or baculum. It appears that this structure plays a role in helping to increase the success of copulation and fertilization of eggs in species where numerous males mate with a single female. Cats have a vestigial baculum or none at all, but the baculum of the walrus can measure up to 54 cm (21 inches).

DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE

Carnivores are found worldwide, although Australia has no native terrestrial members except for the dingo, which was introduced by aboriginal man. Terrestrial forms are naturally absent from most oceanic islands, though the coastlines are usually visited by seals. However, people have taken their pets, as well as a number of wild species, to most islands. For example, a large population of red foxes now inhabits Australia, having been introduced there by foxhunters. Introduction of carnivores to new environments has at times devastated native fauna. In New Zealand, stoats, ferrets, and weasels were introduced to control rabbits, which had also been introduced. As a result, native bird populations were decimated by the carnivores. Birds were also a casualty of mongooses introduced to Hawaii and Fiji, where populations of introduced rodents and snakes had to be controlled. In Europe, American minks released from fur farms contributed to the decline of the native European mink.

North American raccoons (Procyon lotor). Shutterstock.com

Because carnivores are large and depend on meat, there must be fewer carnivores in the environment than the prey animals they feed upon. The maintenance of territories limits the number of predators to the ecosystem’s carrying capacity of prey. In general, carnivores have a population density of approximately 1 per 2.5 square km (1 per square mile). By comparison, omnivorous mammals average about 8 per square km (20 per square mile), and herbivorous rodents attain densities of up to 40,000 per square km (100,000 per square mile) at peak population. Relatively low population density makes carnivores vulnerable to fluctuations of prey density, habitat disturbance, infectious disease, and predation by man. The mobility and adaptability of some carnivores has enabled them to shift ecological roles and survive changes brought about by human activities. For example, the red fox, coyote, raccoon, and striped skunk can all be found in urban and suburban areas of North America. In Europe, the red fox lives in most large cities. Most other species do not fare nearly as well. The gray, or timber, wolf and brown bear once lived across much of the Northern Hemisphere, but their ranges have shrunk following habitat destruction, reduction of prey abundance, and persecution as competitors with man. In Africa and southern Asia the same can be said for lions and tigers. Numerous cats and bears and some seals have become rare and are threatened with extinction.

CLASSIFICATION

There is great diversity in Carnivora, especially among ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Carnivores

- Chapter 2: Bears

- Chapter 3: Canines

- Chapter 4: Felines

- Chapter 5: Weasels and Their Relatives

- Chapter 6: Raccoons, Skunks, Mongooses, Hyenas, and Viverrids

- Chapter 7: Domestic Carnivores

- Appendices

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Carnivores by Britannica Educational Publishing, John P Rafferty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.