- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Climate and Climate Change

About this book

As a fixture in recent headlines, the Earth's climate has commanded much attention. While environmental and atmospheric conditions in large part determine the climate of a region, the impact of human activity has increasingly become a significant factor as well. This is especially true concerning significant climate changes, commonly known as global warming. New technologies and an ever-expanding population have contributed to worldwide climate shifts in ways that are harmful to the planet. The factors affecting climate, the various climate classification systems, and international responses to global warming are all carefully considered in this volume.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Meteorology & ClimatologyCHAPTER 1

CLIMATE

Weather is what we pay attention to on a day-to-day basis: temperature, humidity, precipitation (type, frequency, and amount), atmospheric pressure, and wind (speed and direction). Climate, on the other hand, is the condition of the atmosphere at a particular location over an extended period of time (from one month to many millions of years, but generally 30 years). Climate therefore is the long-term summation of the atmospheric elements (and their variations) that, over short time periods, constitute weather.

From the ancient Greek origins of the word (klíma, “an inclination or slope”—e.g., of the Sun’s rays; a latitude zone of the Earth; a clime) and from its earliest usage in English, climate has been understood to mean the atmospheric conditions that prevail in a given region or zone. In the older form, clime, it was sometimes taken to include all aspects of the environment, including the natural vegetation. The best modern definitions of climate regard it as constituting the total experience of weather and atmospheric behaviour over a number of years in a given region. Climate is not just the “average weather” (an obsolete, and always inadequate, definition). It should include not only the average values of the climatic elements that prevail at different times but also their extreme ranges and variability and the frequency of various occurrences. Just as one year differs from another, decades and centuries are found to differ from one another by a smaller, but sometimes significant, amount. Climate is therefore time-dependent, and climatic values or indexes should not be quoted without specifying what years they refer to.

This book treats the factors that produce weather and climate and the complex processes that cause variations in both. Other major points of coverage include global climatic types and microclimates. The book also considers the impact of climate on human life—as well as the effects of human activities on climate.

SOLAR RADIATION AND TEMPERATURE

Air temperatures have their origin in the absorption of radiant energy from the Sun. They are subject to many influences, including those of the atmosphere, ocean, and land, and are modified by them. As variation of solar radiation is the single most important factor affecting climate, it is considered here first.

THE DISTRIBUTION OF RADIANT ENERGY FROM THE SUN

Nuclear fusion deep within the Sun releases a tremendous amount of energy that is slowly transferred to the solar surface, from which it is radiated into space. The planets intercept minute fractions of this energy, the amount depending on their size and distance from the Sun. A 1-square-metre (11-square-foot) area perpendicular (90°) to the rays of the Sun at the top of Earth’s atmosphere, for example, receives about 1,365 watts of solar power. (This amount is comparable to the power consumption of a typical electric heater.) Because of the slight ellipticity of Earth’s orbit around the Sun, the amount of solar energy intercepted by Earth steadily rises and falls by ±3.4 percent throughout the year, peaking on January 3, when Earth is closest to the Sun. Although about 31 percent of this energy is not used as it is scattered back to space, the remaining amount is sufficient to power the movement of atmospheric winds and oceanic currents and to sustain nearly all biospheric activity.

Most surfaces are not perpendicular to the Sun, and the energy they receive depends on their solar elevation angle. (The maximum solar elevation is 90° for the overhead Sun.) This angle changes systematically with latitude, the time of year, and the time of day. The noontime elevation angle reaches a maximum at all latitudes north of the Tropic of Cancer (23.5° N) around June 22 and a minimum around December 22. South of the Tropic of Capricorn (23.5° S), the opposite holds true, and between the two tropics, the maximum elevation angle (90°) occurs twice a year. When the Sun has a lower elevation angle, the solar energy is less intense because it is spread out over a larger area. Variation of solar elevation is thus one of the main factors that accounts for the dependence of climatic regime on latitude. The other main factor is the length of daylight. For latitudes poleward of 66.5° N and S, the length of day ranges from zero (winter solstice) to 24 hours (summer solstice), whereas the Equator has a constant 12-hour day throughout the year. The seasonal range of temperature consequently decreases from high latitudes to the tropics, where it becomes less than the diurnal range of temperature.

THE EFFECTS OF THE ATMOSPHERE

Of the radiant energy reaching the top of the atmosphere, 46 percent is absorbed by Earth’s surface on average, but this value varies significantly from place to place, depending on cloudiness, surface type, and elevation. If there is persistent cloud cover, as exists in some equatorial regions, much of the incident solar radiation is scattered back to space, and very little is absorbed by Earth’s surface. Water surfaces have low reflectivity (4–10 percent), except in low solar elevations, and are the most efficient absorbers. Snow surfaces, on the other hand, have high reflectivity (40–80 percent) and so are the poorest absorbers. High-altitude desert regions consistently absorb higher-than-average amounts of solar radiation because of the reduced effect of the atmosphere above them.

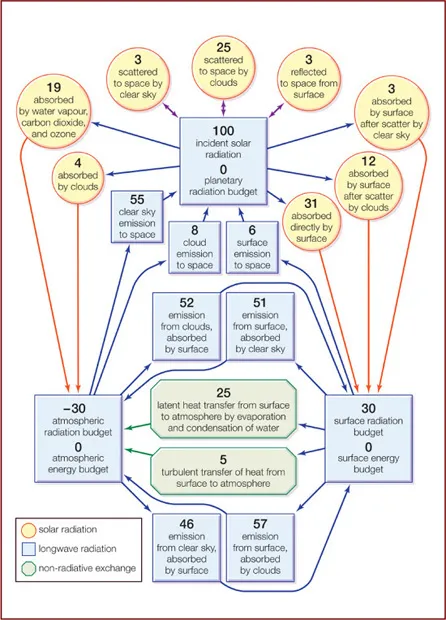

Average exchange of energy between the surface, the atmosphere, and space, as percentages of incident solar radiation (1 unit = 3.4 watts per square metre). Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

An additional 23 percent or so of the incident solar radiation is absorbed on average in the atmosphere, especially by water vapour and clouds at lower altitudes and by ozone (O3) in the stratosphere. Absorption of solar radiation by ozone shields the terrestrial surface from harmful ultraviolet light and warms the stratosphere, producing maximum temperatures of -15 to 10 °C (5 to 50 °F) at an altitude of 50 km (30 miles). Most atmospheric absorption takes place at ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths, so more than 90 percent of the visible portion of the solar spectrum, with wavelengths between 0.4 and 0.7 μm (0.00002 to 0.00003 inch), reaches the surface on a cloud-free day. Visible light, however, is scattered in varying degrees by cloud droplets, air molecules, and dust particles. Blue skies and red sunsets are in effect attributable to the preferential scattering of short (blue) wavelengths by air molecules and small dust particles. Cloud droplets scatter visible wavelengths impartially (hence, clouds usually appear white) but very efficiently, so the reflectivity of clouds to solar radiation is typically about 50 percent and may be as high as 80 percent for thick clouds.

The constant gain of solar energy by Earth’s surface is systematically returned to space in the form of thermally emitted radiation in the infrared portion of the spectrum. The emitted wavelengths are mainly between 5 and 100 μm (0.0002 and 0.004 inch), and they interact differently with the atmosphere compared with the shorter wavelengths of solar radiation. Very little of the radiation emitted by Earth’s surface passes directly through the atmosphere. Most of it is absorbed by clouds, carbon dioxide, and water vapour and is then reemitted in all directions. The atmosphere thus acts as a radiative blanket over Earth’s surface, hindering the loss of heat to space. The blanketing effect is greatest in the presence of low clouds and weakest for clear cold skies that contain little water vapour. Without this effect, the mean surface temperature of 15 °C (59 °F) would be some 30 °C (86 °F) colder. Conversely, as atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, chlorofluorocarbons, and other absorbing gases continue to increase, in large part owing to human activities, surface temperatures should rise because of the capacity of such gases to trap infrared radiation. The exact amount of this temperature increase, however, remains uncertain because of unpredictable changes in other atmospheric components, especially cloud cover. An extreme example of such an effect (commonly dubbed the greenhouse effect) is that produced by the dense atmosphere of the planet Venus, which results in surface temperatures of about 475 °C (887 °F). This condition exists in spite of the fact that the high reflectivity of the Venusian clouds causes the planet to absorb less solar radiation than Earth.

AVERAGE RADIATION BUDGETS

The difference between the solar radiation absorbed and the thermal radiation emitted to space determines Earth’s radiation budget. Since there is no appreciable long-term trend in planetary temperature, it may be concluded that this budget is essentially zero on a global long-term average. Latitudinally, it has been found that much more solar radiation is absorbed at low latitudes than at high latitudes. On the other hand, thermal emission does not show nearly as strong a dependence on latitude, so the planetary radiation budget decreases systematically from the Equator to the poles. It changes from being positive to negative at latitudes of about 40° N and 40° S. The atmosphere and oceans, through their general circulation, act as vast heat engines, compensating for this imbalance by providing nonradiative mechanisms for the transfer of heat from the Equator to the poles.

While Earth’s surface absorbs a significant amount of thermal radiation because of the blanketing effect of the atmosphere, it loses even more through its own emission and thus experiences a net loss of long-wave radiation. This loss is only about 14 percent of the amount emitted by the surface and is less than the average gain of total absorbed solar energy. Consequently, the surface has on average a positive radiation budget.

By contrast, the atmosphere emits thermal radiation both to space and to the surface, yet it receives long-wave radiation back from only the latter. This net loss of thermal energy cannot be compensated for by the modest gain of absorbed solar energy within the atmosphere. The atmosphere thus has a negative radiation budget, equal in magnitude to the positive radiation budget of the surface but opposite in sign. Nonradiative heat transfer again compensates for the imbalance, this time largely by vertical atmospheric motions involving the evaporation and condensation of water.

SURFACE-ENERGY BUDGETS

The rate of temperature change in any region is directly proportional to the region’s energy budget and inversely proportional to its heat capacity. While the radiation budget may dominate the average energy budget of many surfaces, nonradiative energy transfer and storage also are generally important when local changes are considered.

Foremost among the cooling effects is the energy required to evaporate surface moisture, which produces atmospheric water vapour. Most of the latent heat contained in water vapour is subsequently released to the atmosphere during the formation of precipitating clouds, although a minor amount may be returned directly to the surface during dew or frost deposition. Evaporation increases with rising surface temperature, decreasing relative humidity, and increasing surface wind speed. Transpiration by plants also increases evaporation rates, which explains why the temperature in an irrigated field is usually lower than that over a nearby dry road surface.

Another important nonradiative mechanism is the exchange of heat that occurs when the temperature of the air is different from that of the surface. Depending on whether the surface is warmer or cooler than the air next to it, heat is transferred to or from the atmosphere by turbulent air motion (more loosely, by convection). This effect also increases with increasing temperature difference and with increasing surface wind speed. Direct heat transfer to the air may be an important cooling mechanism that limits the maximum temperature of hot dry surfaces. Alternatively, it may be an important warming mechanism that limits the minimum temperature of cold surfaces. Such warming is sensitive to wind speed, so calm conditions promote lower minimum temperatures.

In a similar category, whenever a temperature difference occurs between the surface and the medium beneath the surface, there is a transfer of heat to or from the medium. In the case of land surfaces, heat is transferred by conduction, a process where energy is conveyed through a material from one atom or molecule to another. In the case of water surfaces, the transfer is by convection and may consequently be affected by the horizontal transport of heat within large bodies of water.

TEMPERATURE

The temperature of the air is one of the most important determinants of Earth’s climate. Although the global average air temperature does not change much from day to day or year to year, the mean temperature of any particular location may differ substantially from other points on Earth’s surface. A location’s mean temperature depends on geographic factors and how air and water distribute heat to that location. The temperature of a place at any single point in time varies according to time of day, season, the altitude of the location, and other factors.

THE GLOBAL VARIATION OF MEAN TEMPERATURE

Global variations of average surface-air temperatures are largely due to latitude, continentality, ocean currents, and prevailing winds.

The effect of latitude is evident in the large north-south gradients in average temperature that occur at middle and high latitudes in each winter hemisphere. These gradients are due mainly to the rapid decrease of available solar radiation but also in part to the higher surface reflectivity at high latitudes associated with snow and ice and low solar elevations. A broad area of the tropical ocean, by contrast, shows little temperature variation.

Continentality is a measure of the difference between continental and marine climates and is mainly the result of the increased range of temperatures that occurs over land compared with water. This difference is a consequence of the much lower effective heat capacities of land surfaces as well as of their generally reduced evaporation rates. Heating or cooling of a land surface takes place in a thin layer, the depth of which is determined by the ability of the ground to conduct heat. The greatest temperature changes occur for dry, sandy soils, because they are poor cond...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Climate

- Chapter 2: Climatic Classification

- Chapter 3: Climate and Life

- Chapter 4: Climate Change

- Chapter 5: Global Warming

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Climate and Climate Change by Britannica Educational Publishing, John P Rafferty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Meteorology & Climatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.