- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Deserts and Steppes

About this book

Characterized by uncompromising climate, sparse population density, and extreme aridity, deserts, steppes, and scrublands represent some of the least accessible regions on the planet. However, despite the severity of these ecosystems, they still boast mesmerizing terrains and are capable of supporting diverse animal groups and plant varieties as well as nomadic human inhabitants. This volume tours the alluring landscapes and ecosystems of the unique deserts and steppes of the world and introduces readers to the unique populations that call them home.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE DESERT

A desert is any large, extremely dry area of land with sparse vegetation. It is one of the Earth’s major types of ecosystems, supporting a community of distinctive plants and animals specially adapted to the harsh environment. According to some definitions, any environment that is almost completely free of plants is considered desert, including regions too cold to support vegetation—i.e., “frigid deserts.” Other definitions use the term to apply only to hot and temperate deserts, a restriction followed in this account. The unusually dry conditions and poorly developed soils of deserts lead to the distinctive landforms associated with these regions—for instance, bare rocky or gravelly plains or huge shifting sand hills known as dunes. Flat salt-encrusted depressions known as playas are frequently found. Life exists in extremely dry conditions, but only in delicate balance with an environment that is subject to harsh conditions. It is now clear that in several regions desert environments are expanding—a process called desertification. This process results from various factors, including climatic variation and human activities. In areas where the vegetation is already under stress, periods of drier than average weather may cause degradation of the vegetation. If the pressures are maintained, soil loss and irreversible change in the ecosystem may ensue, so that areas formerly under savanna or scrubland vegetation are reduced to desert.

DESERT ENVIRONMENTS

Desert environments are so dry that they support only extremely sparse vegetation; trees are usually absent and, under normal climatic conditions, shrubs or herbaceous plants provide only very incomplete ground cover. Extreme aridity renders some deserts virtually devoid of plants; however, this barrenness is believed to be due in part to the effects of human disturbance, such as heavy grazing of cattle, on an already stressed environment.

This map shows the world’s deserts and other arid regions. NASA

ORIGIN OF DESERT ENVIRONMENTS

The desert environments of the present are, in geologic terms, relatively recent in origin. They represent the most extreme result of the progressive cooling and consequent aridification of global climates during the Cenozoic Era (65.5 million years ago to the present), which also led to the development of savannas and scrublands in the less arid regions near the tropical and temperate margins of the developing deserts. It has been suggested that many typical modern desert plant families, particularly those with an Asian centre of diversity such as the chenopod and tamarisk families, first appeared in the Miocene Epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), evolving in the salty, drying environment of the disappearing Tethys Sea along what is now the Mediterranean–Central Asian axis.

Deserts also probably existed much earlier, during former periods of global arid climate in the lee of mountain ranges that sheltered them from rain or in the centre of extensive continental regions. However, this would have been primarily before the evolution of angiosperms (flowering plants, the group to which most present-day plants, including those of deserts, belong). Only a few primitive plants, which may have been part of the ancient desert vegetation, occur in present-day deserts. One example is the bizarre conifer relative Welwitschia in the Namib of southwestern Africa. Welwitschia has only two leaves, which are leathery, straplike organs that emanate from the middle of a massive, mainly subterranean woody stem. These leaves grow perpetually from their bases and erode progressively at their ends. The Namib also harbours several other plants and animals peculiarly adapted to the arid environment, suggesting that it might have a longer continuous history of arid conditions than most other deserts.

Desert floras and faunas initially evolved from ancestors in moister habitats, an evolution that occurred independently on each continent. However, a significant degree of commonality exists among the plant families that dominate different desert vegetations. This is due in part to intrinsic physiologic characteristics in some widespread desert families that preadapt the plants to an arid environment; it also is a result of plant migration occurring through chance seed dispersal among desert regions.

Such migration was particularly easy between northern and southern desert regions in Africa and in the Americas during intervals of drier climate that have occurred in the past two million years. This migration is reflected in close floristic similarities currently observed in these places. For example, the creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), although now widespread and common in North American hot deserts, was probably a natural immigrant from South America as recently as the end of the last Ice Age about 11,700 years ago.

Migration between discrete desert regions also has been relatively easier for those plants adapted to survival in saline soils because such conditions occur not only in deserts but also in coastal habitats. Coasts can therefore provide migration corridors for salt-tolerant plants, and in some cases the drifting of buoyant seeds in ocean currents can provide a transport mechanism between coasts. For example, it is thought that the saltbush or chenopod family of plants reached Australia in this way, initially colonizing coastal habitats and later spreading into the inland deserts.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS

Deserts are varied and variable environments, and it is impossible to arrive at a concise definition that satisfies every case. However, their most fundamental characteristic is a shortage of available moisture for plants, resulting from an imbalance between precipitation and evapotranspiration. This situation is exacerbated by considerable variability in the timing of rainfall, low atmospheric humidity, high daytime temperatures, and winds.

Average annual precipitation ranges from almost zero in some South American coastal deserts and Libyan deserts to about 600 mm (24 inches) in deserts in Madagascar, although most recognized deserts have an annual rainfall below 400 mm (16 inches). Some authorities consider 250 mm (10 inches) the upper limit for mean annual precipitation for true deserts, describing places with a mean annual rainfall of between 250 and 400 mm as semideserts. Regions this dry are barely arable and contribute to human food production only by providing grazing lands for livestock.

The arid conditions of the major desert areas result from their position in subtropical regions to either side of the moist equatorial belt. The atmospheric circulation pattern known as the Hadley cell plays an important role in desert climate. In areas close to the Equator, where the amount of incoming solar energy per unit surface area is greatest, air near the ground is heated, then rises, expands, and cools. This process leads to the condensation of moisture and to precipitation. At high levels in the atmosphere, the risen air moves away from the equatorial region to descend eventually in the subtropics as it cools; it moves back toward the Equator at low altitudes, completing the Hadley cell circulation pattern. The air descending over the subtropics has already lost most of its moisture as rain formed during its previous ascent near the Equator. As it descends it becomes compressed and warmer, its relative humidity falling further. Hot deserts occur in those regions to the north and south of the equatorial belt that lie beneath these descending, dry air masses. This pattern may be interrupted where local precipitation is increased, especially on the east sides of continents where winds blow onshore, carrying moisture picked up over the ocean. Conversely, deserts may be found elsewhere, as in the lee of mountain ranges, where air is forced to rise, cool, and lose moisture as rain falling on the windward slopes.

Rainfall in deserts is usually meagre. In some cases several years may pass without rain; for example, at Cochones, Chile, no rain fell at all in 45 consecutive years between 1919 and 1964. Usually, however, rain falls in deserts for at least a few days each year—typically 15 to 20 days. When precipitation occurs, it may be very heavy for short periods. For instance, 14 mm (0.5 inch) fell at Mash’abe Sade, Israel, in only seven minutes on Oct. 5, 1979, and in southwestern Madagascar the entire annual rainfall commonly occurs as heavy showers falling within a single month. Such rainfall usually occurs only over small areas and results from local convectional cells, with more widespread frontal rain being restricted to the southern and northern fringes of deserts. In some local desert showers, the rain falling from clouds evaporates before it reaches the ground. Regions near the equatorial margins of hot deserts receive most of their rain in summer—June to August in the Northern Hemisphere and December to February in the Southern Hemisphere—while those near the temperate margins receive most of their rainfall in winter. Rain is particularly erratic and equally unlikely to occur in all seasons in intermediate regions.

In some deserts that are located near coasts, such as the Namib of southwestern Africa and those of the west coasts of the Americas in California and Peru, fog is an important source of moisture that is otherwise scarce. Moisture droplets settle from the fog onto plants and then may drip onto the soil or be absorbed directly by plant shoots. Dew also may be significant, although not in deserts in the central parts of continents where atmospheric humidity is consistently very low.

In most desert regions atmospheric humidity is usually too low to permit formation of fog or dew to any significant extent. Potential evaporation rates (the rate of evaporation that would occur if water were continually present) are correspondingly high, typically 2,500 to 3,500 mm (100 to 140 inches) per year, with as much as 4,262 mm (168 inches) potential evaporation per year having been recorded in Death Valley in California. Winds are not unusually strong or frequent in comparison with adjacent environments, but the general lack of vegetation in deserts exacerbates the effect of wind at ground level. Winds can induce the erosion of fine materials and the evaporation of moisture and thereby help determine which plants survive in the desert.

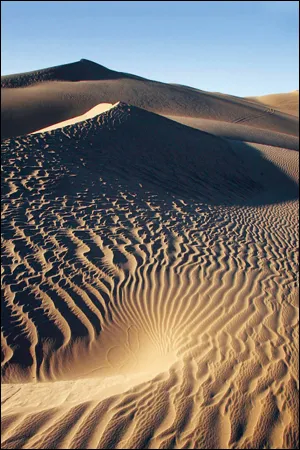

Sand dunes in the Sahara, Morocco. Goodshoot/Jupiterimages

Hot deserts, as their name indicates, experience very high temperatures by day, especially in summer. Absolute maximum air temperatures in all hot deserts exceed 40 °C (104 °F), and the highest value recorded, in Libya, is 58 °C (136.4 °F). The temperature of the soil surface can rise even beyond that of the air, with values as high as 78 °C (172 °F) recorded in the Sahara. However, night temperatures can fall dramatically, because the same lack of cloud cover that admits high levels of incoming solar radiation during the day also allows rapid loss of energy through long-wave radiation to the sky at night. Absolute minimum temperatures, except in desert areas close to the sea, are generally below the freezing point. Typical mean annual temperatures are between 20 °C (68 °F) and 25 °C (77 °F).

Temperate or cold deserts occur in temperate regions at higher latitudes—and therefore colder temperatures—than those at which hot deserts are found. These dry environments are caused by either remoteness from the coast, which results in low atmospheric humidity from a lack of onshore winds, or the presence of high mountains separating the desert from the coast. The largest area of temperate desert lies in Central Asia, with smaller areas in western North America, southeastern South America, and southern Australia. While they experience lower temperatures than the more typical hot deserts, temperate deserts are similar in aridity and consequent environmental features including landforms and soils.

The peculiar climatic environment of deserts has favoured the development of certain characteristic landforms. Stony plains called regs or gibber plains are widespread, their surface covered by desert pavement consisting of coarse gravel and stones coated with a patina of dark “desert varnish” (a glossy dark surface cover consisting of oxides of iron). Rocky, boulder-strewn plateaus cut by dry, usually steep-sided valleys called wadis are also found in deserts in many parts of the world. The local topographic and microclimatic variations produced by this rugged surface, and the opportunities for runoff—and in a few places surface accumulation—of rainwater, are important in providing localized habitats for plants and animals. Large areas of loose, mobile sand provide the harshest and poorest of the major desert habitat types.

Desert soils are mainly immature, weakly developed in terms of their soil profiles, and mostly alkaline. Sands, sandy or gravelly loams, shallow stony soils, and alluvium (material deposited by rivers and streams) and scree-derived deposits (rocky material at the base of cliffs) predominate. Although almost always dry, these soils may support well-developed microbial communities, particularly in association with roots. Domestic animals, however, can have a deleterious impact by trampling and compacting the soil; this activity can reduce the infiltration of water and damage vegetation, leading to erosion and redistribution of soil materials.

DESERT FLORA AND FAUNA

In most cases floristic links among desert regions are indicated by the presence of related species; it is unusual for identical species to be found in more than one region, except where they have been introduced by humans. (One notable exception is the prickly saltwort [Salsola kali], which occurs in deserts in Central Asia, North Africa, California, and Australia, as well as in many saline coastal areas.) Floristic similarities among desert regions are particularly obvious where no wide barriers of ocean or humid vegetation exist to restrict plant migration. Floristic links can be observed across the great expanse of desert from the Sahara to Central Asia, despite climatic contrasts between the hot environments in areas in and around North Africa and the much colder, though still dry, regions to the northeast. Floristic links are also pronounced from north to south in Africa and the Americas. As expected, the more isolated Australian desert flora has fewer similarities to the floras of other regions.

The daisy family is the most diverse plant family in deserts overall; it is especially numerous in Australia, southern Africa, the Middle East, and North America. However, except for the widespread Artemisia (wormwood) and Senecio, which are ubiquitous, different genera in this family are found in different desert regions. Although grasses predominate in the deserts of Iran, the Sahara, and the Thar Desert of India, members of the daisy family are almost as diverse here also. Another family well represented in deserts and other vegetation types is the bean family.

More locally significant plant families in deserts include the ice plant and lily families in Africa; the cabbage family from the Sahara to Iran; the carnation family in the Middle East; and the myrtle, protea, and casuarina families in Australia. All families also occur in other vegetation types in those same regions and represent elements of regionally prominent groups that have adapted to arid environments.

Members of some other plant families are common in desert vegetation but are not prominent components of other vegetation types. The best example is the chenopod or saltbush family, which is varied and diverse in arid and semiarid regions of Australia, North America, and from the Sahara ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Desert

- Chapter 2: Major and Other Notable Deserts of the World

- Chapter 3: Steppes and Scrublands

- Chapter 4: Major and Notable Semiarid Regions of the World

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Deserts and Steppes by Britannica Educational Publishing, John P Rafferty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.