eBook - ePub

Geochronology, Dating, and Precambrian Time

The Beginning of the World as We Know It

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geochronology, Dating, and Precambrian Time

The Beginning of the World as We Know It

About this book

Though it encompasses the majority of the Earth's history, much about Precambrian time still remains unknown to us. With its climate extremes and unstable surfaces, Precambrian Earth hardly resembled the planet we see today. Yet for all its differences, it made the existence of future generations possible. This volume helps unlock the mysteries of prehistory by considering available geologic evidence while providing a deep dive into the finesses of geochronology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geochronology, Dating, and Precambrian Time by Britannica Educational Publishing, John P Rafferty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geology & Earth Sciences. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Geology & Earth SciencesCHAPTER 1

GEOLOGIC TIME

Geologic time spans Earth’s geologic history. It extends from about 4.6 billion years ago (corresponding to the age of Earth’s formation) to the present day. Some scientists maintain, however, that geologic time begins with the oldest known rocks that were created some 4.4 billion years ago.

The geologic time scale is the “calendar” for events in Earth history. It subdivides all time since the end of the Earth’s formative period as a planet (nearly 4.6 billion years ago) into named units of abstract time: the latter, in descending order of duration, are eons, eras, periods, and epochs. The enumeration of these geologic time units is based on stratigraphy, which is the correlation and classification of rock strata. The fossil forms that occur in these rocks provide the chief means of establishing a geologic time scale. Because living things have undergone evolutionary changes over geologic time, particular kinds of organisms are characteristic of particular parts of the geologic record. By correlating the strata in which certain types of fossils are found, the geologic history of various regions (and of the Earth as a whole) can be reconstructed. The relative geologic time scale developed from the fossil record has been numerically quantified by means of absolute dates obtained with radiometric dating methods.

GEOCHRONOLOGY

Geochronology is the field of scientific investigation concerned with determining the age and history of the Earth’s rocks and rock assemblages. Such time determinations are made and the record of past geologic events is deciphered by studying the distribution and succession of rock strata, as well as the character of the fossil organisms preserved within the strata.

The Earth’s surface is a complex mosaic of exposures of different rock types that are assembled in an astonishing array of geometries and sequences. Individual rocks in the myriad of rock outcroppings (or in some instances shallow subsurface occurrences) contain certain materials or mineralogic information that can provide insight as to their “age.”

For years investigators determined the relative ages of sedimentary rock strata on the basis of their positions in an outcrop and their fossil content. According to a longstanding principle of the geosciences, that of superposition, the oldest layer within a sequence of strata is at the base and the layers are progressively younger with ascending order. The relative ages of the rock strata deduced in this manner can be corroborated and at times refined by the examination of the fossil forms present. The tracing and matching of the fossil content of separate rock outcrops (that is, the correlation process) eventually enabled investigators to integrate rock sequences in many areas of the world and construct a relative geologic time scale.

Scientific knowledge of the Earth’s geologic history has advanced significantly since the development of radiometric dating, a method of age determination based on the principle that radioactive atoms in geologic materials decay at constant, known rates to daughter atoms. Radiometric dating has provided not only a means of numerically quantifying geologic time but also a tool for determining the age of various rocks that predate the appearance of life-forms.

EARLY VIEWS AND DISCOVERIES

Some estimates suggest that as much as 70 percent of all rocks outcropping from the Earth’s surface are sedimentary. Preserved in these rocks is the complex record of the many transgressions and regressions of the sea, as well as the fossil remains or other indications of now extinct organisms and the petrified sands and gravels of ancient beaches, sand dunes, and rivers.

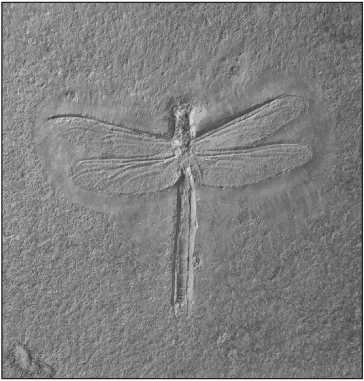

This ancient dragonfly was fossilized in limestone. Many species of dragonflies lived during the Precambrian era. Colin Keates/Dorling Kindersley/Getty Images

Modern scientific understanding of the complicated story told by the rock record is rooted in the long history of observations and interpretations of natural phenomena extending back to the early Greek scholars. Xenophanes of Colophon (560?–478? BCE), for one, saw no difficulty in describing the various seashells and images of life-forms embedded in rocks as the remains of long-deceased organisms. In the correct spirit but for the wrong reasons, Herodotus (5th century BCE) felt that the small discoidal nummulitic petrifactions (actually the fossils of ancient lime-secreting marine protozoans) found in limestones outcropping at al-Jīzah, Egypt, were the preserved remains of discarded lentils left behind by the builders of the pyramids.

These early observations and interpretations represent the unstated origins of what was later to become a basic principle of uniformitarianism, the root of any attempt at linking the past (as preserved in the rock record) to the present. Loosely stated, the principle says that the various natural phenomena observed today must also have existed in the past.

Although quite varied opinions about the history and origins of life and of the Earth itself existed in the pre-Christian era, a divergence between Western and Eastern thought on the subject of natural history became more pronounced as a result of the extension of Christian dogma to the explanation of natural phenomena. Increasing constraints were placed upon the interpretation of nature in view of the teachings of the Bible. This required that the Earth be conceived of as a static, unchanging body, with a history that began in the not too distant past, perhaps as little as 6,000 years earlier. It also required an end, according to the scriptures, that was in the not too distant future. This biblical history of the Earth left little room for interpreting the Earth as a dynamic, changing system. Past catastrophes, particularly those that may have been responsible for altering the Earth’s surface such as the great flood of Noah, were considered an artifact of the earliest formative history of the Earth. As such, they were considered unlikely to recur on what was thought to be an unchanging world.

With the exception of a few prescient individuals such as Roger Bacon (c. 1220–92) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), no one stepped forward to champion an enlightened view of the natural history of the Earth until the mid-17th century. Leonardo seems to have been among the first of the Renaissance scholars to “rediscover” the uniformitarian dogma through his observations of fossil marine organisms and sediments exposed in the hills of northern Italy. He recognized that the marine organisms now found as fossils in rocks exposed in the Tuscan Hills were simply ancient animals that lived in the region when it had been covered by the sea and were eventually buried by muds along the seafloor. He also recognized that the rivers of northern Italy, flowing south from the Alps and emptying into the sea, had done so for a very long time.

In spite of this deductive approach to interpreting natural events and the possibility that they might be preserved and later observed as part of a rock outcropping, little or no attention was given to the history—namely, the sequence of events in their natural progression—that might be preserved in these same rocks.

THE PRINCIPLE OF SUPERPOSITION OF ROCK STRATA

In 1669 the Danish-born natural scientist Nicolaus Steno (né Niels Steensen) published his noted treatise De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus (Eng. trans. The Prodromus of Nicolaus Steno’s Dissertation Concerning a Solid Body Enclosed by Process of Nature Within a Solid). This seminal work laid the essential framework for the science of geology by showing in very simple fashion that the layered rocks of Tuscany exhibit sequential change—that they contain a record of past events. Following from this observation, Steno concluded that the Tuscan rocks demonstrated superpositional relationships: rocks deposited first lie at the bottom of a sequence, while those deposited later are at the top. This is the crux of what is now known as the principle of superposition. Steno put forth still another idea—that layered rocks were likely to be deposited horizontally. Therefore, even though the strata of Tuscany were (and still are) displayed in anything but simple geometries, Steno’s elucidation of these fundamental principles relating to the formation of stratified rock made it possible to work out not only superpositional relationships within rock sequences but also the relative age of each layer.

With the publication of the Prodromus and the ensuing widespread dissemination of Steno’s ideas, other natural scientists of the latter part of the 17th and early 18th centuries applied them to their own work. The early English geologist John Strachey, for example, produced in 1725 what may well have been the first modern geologic maps of rock strata. He also described the succession of strata associated with coal-bearing sedimentary rocks in Somersetshire, the same region of England where he had mapped the rock exposures.

THE CLASSIFICATION OF STRATIFIED ROCKS

In 1756 Johann Gottlob Lehmann of Germany reported on the succession of rocks in the southern part of his country and the Alps, measuring and describing their compositional and spatial variation. While making use of Steno’s principle of superposition, Lehmann recognized the existence of three distinct rock assemblages: (1) a successionally lowest category, the Primary (Urgebirge), composed mainly of crystalline rocks, (2) an intermediate category, or the Secondary (Flötzgebirge), composed of layered or stratified rocks containing fossils, and (3) a final or successionally youngest sequence of alluvial and related unconsolidated sediments (Angeschwemmtgebirge) thought to represent the most recent record of the Earth’s history.

German geologist Johann Gottlob Lehmann. Apic/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

This threefold classification scheme was successfully applied with minor alterations to studies in other areas of Europe by three of Lehmann’s contemporaries. In Italy, again in the Tuscan Hills in the vicinity of Florence, Giovanni Arduino—regarded by many as the father of Italian geology—proposed a four-component rock succession. His Primary and Secondary divisions are roughly similar to Lehmann’s Primary and Secondary categories. In addition, Arduino proposed another category, the Tertiary division, to account for poorly consolidated though stratified fossil-bearing rocks that were superpositionally older than the (overlying) alluvium but distinct and separate from the hard (underlying) stratified rocks of the Secondary.

In two separate publications, one that appeared in 1762 and the second in 1773, Georg Christian Füchsel also applied Lehmann’s earlier concepts of superposition to another sequence of stratified rocks in southern Germany. While using upwards of nine separate categories of sedimentary rocks, Füchsel essentially identified discrete rock bodies of unique composition, lateral extent, and position within a rock succession. (These rock bodies would constitute formations in modern terminology.)

Nearly 1,000 kilometres (620 miles) to the east, the German naturalist Peter Simon Pallas was studying rock sequences exposed in the southern Urals of eastern Russia. His 1777 report differentiated a threefold division of rock, essentially reiterating Lehmann’s work by extension.

Thus, by the latter part of the 18th century, the superpositional concept of rock strata had been firmly established through a number of independent investigations throughout Europe. Although Steno’s principles were being widely applied, there remained to be answered a number of fundamental questions relating to the temporal and lateral relationships that seemed to exist among these disparate European sites. Were these various German, Italian, and Russian sites at which Lehmann’s threefold rock succession was recognized contemporary? Did they record the same series of geologic events in the Earth’s past? Were the various layers at each site similar to those of other sites? In short, was correlation among these various sites now possible?

THE EMERGENCE OF MODERN GEOLOGIC THOUGHT

Inherent in many of the assumptions underlying the early attempts at interpreting natural phenomena in the latter part of the 18th century was the ongoing controversy between the biblical view of Earth processes and history and a more direct approach based on what could be observed and understood from various physical relationships demonstrable in nature. A substantial amount of information about the compositional character of many rock sequences was beginning to accumulate at this time. Abraham Gottlob Werner, a scholar of wide repute and following from the School of Mining in Freiberg, Ger., was very successful in reaching a compromise between what could be said to be scientific “observation” and biblical “fact.” Werner’s theory was that all rocks (including the sequences being identified in various parts of Europe at that time) and the Earth’s topography were the direct result of either of two processes: (1) deposition in the primeval ocean, represented by the Noachian flood (his two “Universal,” or Primary, rock series), or (2) sculpturing and deposition during the retreat of this ocean from the land (his two “Partial,” or disintegrated, rock series). Werner’s interpretation, which came to represent the so-called Neptunist conception of the Earth’s beginnings, found widespread and nearly universal acceptance owing in large part to its theological appeal and to Werner’s own personal charisma.

One result of Werner’s approach to rock classification was that each unique lithology in a succession implied its own unique time of formation during the Noachian flood and a universal distribution. As more and more comparisons were made of diverse rock outcroppings, it began to become apparent that Werner’s interpretation did not “universally” apply. Thus, an increasingly vocal challenge to the Neptunist theory arose.

JAMES HUTTON’S RECOGNITION OF THE GEOLOGIC CYCLE

In the late 1780s, the Scottish scientist James Hutton launched an attack on much of the geologic dogma that had its basis in either Werner’s Neptunist approach or its corollary that the prevailing configuration of the Earth’s surface is largely the result of past catastrophic events which have no modern counterparts. Perhaps the quintessential spokesman for the application of the scientific method in solving problems presented in the complex world of natural history, Hutton took issue with the catastrophist and Neptunist approach to interpreting rock histories and instead used deductive reasoning to explain what he saw. By Hutton’s account, the Earth could not be viewed as a simple, static world not currently undergoing change. Ample evidence from Hutton’s Scotland provided the key to unraveling the often thought but still rarely stated premise that events occurring today at the Earth’s surface—namely erosion, transportation and deposition of sediments, and volcanism—seem to have their counterparts preserved in the rocks. The rocks of the Scottish coast and the area around Edinburgh proved the catalyst for his argument that the Earth is indeed a dynamic, ever-changing system, subject to a sequence of recurrent cycles of erosion and deposition and of subsidence and uplift. Hutton’s formulation of the principle of uniformitarianism—which holds that Earth processes occurring today had their counterparts in the ancient past, while not the first time that this general concept was articulated—was probably the most important geologic concept developed out of rational scientific thought of the 18th century. The publication of Hutton’s two-volume Theory of the Earth in 1795 firmly established him as one of the founders of modern geologic thought.

It was not easy for Hutton to popularize his ideas, however. The Theory of the Earth certainly did set the fundamental principles of geology on a firm basis, and several of Hutton’s colleagues, notably John Playfair with his Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth (1802), attempted to counter the entrenched Wernerian influence of the time. Nonetheless, another 30 years were to pass before Neptunist and catastrophist views of Earth history were finally replaced by those grounded in a uniformitarian approach.

This gradual unseating of the Neptunist theory resulted from the accumulated evidence that increasingly called into question the applicability of Werner’s Universal and Partial formations in describing various rock successions. Clearly, not all assignable rock types would fit into Werner’s categories, either superpositionally in some local succession or as a unique occurrence at a given site. Also, it was becoming increasingly difficult to accept certain assertions of Werner that some rock types (such as basalt) are chemical precipitates from the primordial ocean. It was this latter observation that finally rendered the Neptunist theory unsustainable. Hutton observed that basaltic rocks exposed in the Salisbury Crags, just on the outskirts of Edinburgh, seemed to have baked adjacent enclosing sediments lying both b...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Geologic Time

- Chapter 2: Dating

- Chapter 3: Precambrian Time

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- For Further Reading

- Index