eBook - ePub

Modern Philosophy

From 1500 CE to the Present

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Concerned more with rationality, human nature, and human interaction with society and the world than the theological questions of the Middle Ages, contemporary philosophy has advanced study of the limits of the human mind. This insightful volume traces the evolution of present-day Western philosophy and the diverging methods of inquiry that continue to inform a wide range of disciplines.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Modern Philosophy by Britannica Educational Publishing, Brian Duignan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Modern Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Modern PhilosophyCHAPTER 1

PHILOSOPHY IN THE RENAISSANCE

The philosophy of a period arises as a response to social need, and the development of philosophy in the history of Western civilization since the Renaissance has, thus, reflected the process in which creative philosophers have responded to the unique challenges of each stage in the development of Western culture itself.

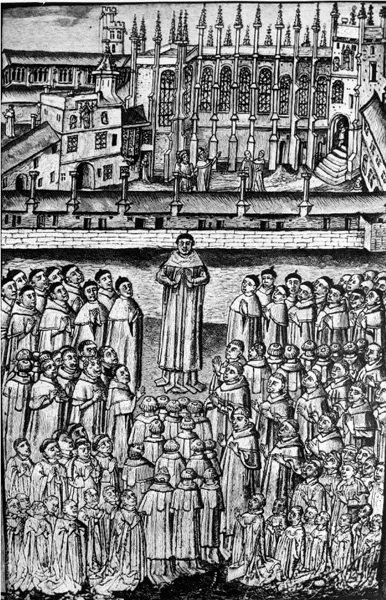

The career of philosophy—how it views its tasks and functions, how it defines itself, the special methods it invents for the achievement of philosophical knowledge, the literary forms it adopts and uses, its conception of the scope of its subject matter, and its changing criteria of meaning and truth—hinges on the mode of its successive responses to the challenges of the social structure within which it arises. Thus, Western philosophy in the Middle Ages was primarily a Christian philosophy, complementing the divine revelation, reflecting the feudal order in its cosmology, and devoting itself in no small measure to the institutional tasks of the Roman Catholic Church. It was no accident that the major philosophical achievements of the 13th and 14th centuries were the work of churchmen who also happened to be professors of theology at the Universities of Oxford and Paris.

The Renaissance of the late 15th and 16th centuries presented a different set of problems and therefore suggested different lines of philosophical endeavour. What is called the European Renaissance followed the introduction of three novel mechanical inventions from the East: gunpowder, block printing from movable type, and the compass. The first was used to explode the massive fortifications of the feudal order and thus became an agent of the new spirit of nationalism that threatened the rule of churchmen—and, indeed, the universalist emphasis of the church itself—with a competing secular power. The second, printing, widely propagated knowledge, secularized learning, reduced the intellectual monopoly of an ecclesiastical elite, and restored the literary and philosophical classics of Greece and Rome. The third, the compass, increased the safety and scope of navigation, produced the voyages of discovery that opened up the Western Hemisphere, and symbolized a new spirit of physical adventure and a new scientific interest in the structure of the natural world.

The University of Oxford proved to be fertile ground for significant philosophical achievements. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Each invention, with its wider cultural consequences, presented new intellectual problems and novel philosophical tasks within a changing political and social environment. As the power of a single religious authority slowly eroded under the influence of the Protestant Reformation and as the prestige of the universal Latin language gave way to vernacular tongues, philosophers became less and less identified with their positions in the ecclesiastical hierarchy and more and more identified with their national origins. The works of Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–80), Thomas Aquinas (c. 1224–74), Bonaventure (c. 1217–74), and John Duns Scotus (1266–1308) were basically unrelated to the countries of their birth. The philosophy of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) was directly related to Italian experience, however, and that of Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was English to the core, as was that of Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) in the early modern period. Likewise, the thought of René Descartes (1596–1650) set the standard and tone of intellectual life in France for 200 years.

Knowledge in the contemporary world is conventionally divided among the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities. In the Renaissance, however, fields of learning had not yet become so sharply departmentalized. In fact, each division arose in the comprehensive and broadly inclusive area of philosophy. As the Renaissance mounted its revolt against the reign of religion and therefore reacted against the church, against authority, against Scholasticism, and against Aristotle (384–322 BCE), there was a sudden blossoming of interest in problems centring on humankind, civil society, and nature. These three areas corresponded exactly to the three dominant strands of Renaissance philosophy: humanism, political philosophy, and the philosophy of nature.

THE HUMANISTIC BACKGROUND

The term Middle Ages was coined by scholars in the 15th century to designate the interval between the downfall of the Classical world of Greece and Rome and its rediscovery at the beginning of their own century, a revival in which they felt they were participating. Indeed, the notion of a long period of cultural darkness had been expressed by Petrarch (1304–74) even earlier. Events during the last three centuries of the Middle Ages, particularly beginning in the 12th century, set in motion a series of social, political, and intellectual transformations that culminated in the Renaissance. These included the increasing failure of the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire to provide a stable and unifying framework for the organization of spiritual and material life, the rise in importance of city-states and national monarchies, the development of national languages, and the breakup of the old feudal structures.

Although the spirit of the Renaissance ultimately took many forms, it was expressed earliest by the intellectual movement called humanism. Humanism was initiated by secular men of letters rather than by the scholar-clerics who had dominated medieval intellectual life and had developed the Scholastic philosophy. Humanism began and achieved fruition first in Italy. Its predecessors were men like Dante (1265–1321) and Petrarch, and its chief protagonists included Gianozzo Manetti (1396–1459), Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370–1444), Marsilio Ficino (1433–99), Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–94), Lorenzo Valla (1407–57), and Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406). The fall of Constantinople in 1453 provided humanism with a major boost, for many eastern scholars fled to Italy, bringing with them important books and manuscripts and a tradition of Greek scholarship.

Humanism had several significant features. First, it took human nature in all of its various manifestations and achievements as its subject. Second, it stressed the unity and compatibility of the truth found in all philosophical and theological schools and systems, a doctrine known as syncretism. Third, it emphasized the dignity of human beings. In place of the medieval ideal of a life of penance as the highest and noblest form of human activity, the humanists looked to the struggle of creation and the attempt to exert mastery over nature. Finally, humanism looked forward to a rebirth of a lost human spirit and wisdom. In the course of striving to recover it, however, the humanists assisted in the consolidation of a new spiritual and intellectual outlook and in the development of a new body of knowledge. The effect of humanism was to help people break free from the mental strictures imposed by religious orthodoxy, to inspire free inquiry and criticism, and to inspire a new confidence in the possibilities of human thought and creations.

Much to his chagrin, the work of Desiderius Erasmus helped spark the Reformation. Kean Collection/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

From Italy the new humanist spirit and the Renaissance it engendered spread north to all parts of Europe, aided by the invention of printing, which allowed the explosive growth of literacy and the greater availability of Classical texts. Foremost among northern humanists was Desiderius Erasmus (1469–1536), whose Praise of Folly (1509) epitomized the moral essence of humanism in its insistence on heartfelt goodness as opposed to formalistic piety. The intellectual stimulation provided by humanists helped spark the Reformation, from which, however, many humanists, including Erasmus, recoiled. By the end of the 16th century, the battle of Reformation and Counter-Reformation had commanded much of Europe’s energy and attention, while the intellectual life was poised on the brink of the Enlightenment.

THE IDEAL OF HUMANITAS

The history of the term humanism is complex but enlightening. It was first employed (as humanismus) by 19th-century German scholars to designate the Renaissance emphasis on classical studies in education. These studies were pursued and endorsed by educators known, as early as the late 15th century, as umanisti—that is, professors or students of Classical literature. The word umanisti derives from the studia humanitatis, a course of classical studies that, in the early 15th century, consisted of grammar, poetry, rhetoric, history, and moral philosophy. The studia humanitatis were held to be the equivalent of the Greek paideia. Their name was itself based on the Latin humanitas, an educational and political ideal that was the intellectual basis of the entire movement. Renaissance humanism in all its forms defined itself in its straining toward this ideal. No discussion of humanism, therefore, can have validity without an understanding of humanitas.

Humanitas meant the development of human virtue, in all its forms, to its fullest extent. The term thus implied not only such qualities as are associated with the modern word humanity—understanding, benevolence, compassion, mercy—but also more aggressive characteristics such as fortitude, judgment, prudence, eloquence, and even love of honour. Consequently, the possessor of humanitas could not be merely a sedentary and isolated philosopher or man of letters but was of necessity a participant in active life. Just as action without insight was held to be aimless and barbaric, insight without action was rejected as barren and imperfect. Humanitas called for a fine balance of action and contemplation, a balance born not of compromise but of complementarity. The goal of such fulfilled and balanced virtue was political, in the broadest sense of the word. The purview of Renaissance humanism included not only the education of the young but also the guidance of adults (including rulers) via philosophical poetry and strategic rhetoric. It included not only realistic social criticism but also utopian hypotheses, not only painstaking reassessments of history but also bold reshapings of the future. In short, humanism called for the comprehensive reform of culture, the transfiguration of what humanists termed the passive and ignorant society of the “dark” ages into a new order that would reflect and encourage the grandest human potentialities. Humanism had an evangelical dimension: it sought to project humanitas from the individual into the state at large.

The wellspring of humanitas was Classical literature. Greek and Roman thought, available in a flood of rediscovered or newly translated manuscripts, provided humanism with much of its basic structure and method. For Renaissance humanists, there was nothing dated or outworn about the writings of Plato (c. 428–348 BCE), Cicero (106–43 BCE), or Livy (59/64 BCE–17 CE). Compared with the typical productions of medieval Christianity, these pagan works had a fresh, radical, almost avant-garde tonality. Indeed, recovering the classics was to humanism tantamount to recovering reality. Classical philosophy, rhetoric, and history were seen as models of proper method—efforts to come to terms, systematically and without preconceptions of any kind, with perceived experience. Moreover, Classical thought considered ethics qua ethics, politics qua politics: it lacked the inhibiting dualism occasioned in medieval thought by the often-conflicting demands of secularism and Christian spirituality. Classical virtue, in examples of which the literature abounded, was not an abstract essence but a quality that could be tested in the forum or on the battlefield. Finally, Classical literature was rich in eloquence. In particular (because humanists were normally better at Latin than they were at Greek), Cicero was considered to be the pattern of refined and copious discourse. In eloquence humanists found far more than an exclusively aesthetic quality. As an effective means of moving leaders or fellow citizens toward one political course or another, eloquence was akin to pure power. Humanists cultivated rhetoric, consequently, as the medium through which all other virtues could be communicated and fulfilled.

Humanism, then, may be accurately defined as that Renaissance movement that had as its central focus the ideal of humanitas. The narrower definition of the Italian term umanisti notwithstanding, all the Renaissance writers who cultivated humanitas, and all their direct “descendants,” may be correctly termed humanists.

BASIC PRINCIPLES AND ATTITUDES

Underlying the early expressions of humanism were principles and attitudes that gave the movement a unique character and would shape its future development.

CLASSICISM

Early humanists returned to the classics less with nostalgia or awe than with a sense of deep familiarity, an impression of having been brought newly into contact with expressions of an intrinsic and permanent human reality. Petrarch dramatized his feeling of intimacy with the classics by writing “letters” to Cicero and Livy. Salutati remarked with pleasure that possession of a copy of Cicero’s letters would make it possible for him to talk with Cicero. Machiavelli would later immortalize this experience in a letter that described his own reading habits in ritualistic terms:

Evenings I return home and enter my study; and at its entrance I take off my everyday clothes, full of mud and dust, and don royal and courtly garments; decorously reattired, I enter into the ancient sessions of ancient men. Received amicably by them, I partake of such food as is mine only and for which I was born. There, without shame, I speak with them and ask them about the reason for their actions; and they in their humanity respond to me.

Machiavelli’s term umanità (“humanity”), meaning more than simply kindness, is a direct translation of the Latin humanitas. In addition to implying that he shared with the ancients a sovereign wisdom of human affairs, Machiavelli also describes that theory of reading as an active, and even aggressive, pursuit common among humanists. Possessing a text and understanding its words were insufficient. Analytic ability and a questioning attitude were essential before a reader could truly enter the councils of the great. These councils, moreover, were not merely serious and ennobling. They held secrets available only to the astute, secrets the knowledge of which could transform life from a chaotic miscellany into a crucially heroic experience. Classical thought offered insight into the heart of things. In addition, the classics suggested methods by which, once known, human reality could be transformed from an accident of history into an artifact of will. Antiquity was rich in examples—actual or poetic—of epic action, victorious eloquence, and applied understanding. Carefully studied and well employed, Classical rhetoric could implement enlightened policy, while Classical poetics could carry enlightenment into the very souls of human beings. In a manner that might seem paradoxical to more modern minds, humanists associated Classicism with the future.

REALISM

Early humanists shared in large part a realism that rejected traditional assumptions and aimed instead at the objective analysis of perceived experience. To humanism is owed the rise of modern social science, which emerged not as an academic discipline but rather as a practical instrument of social self-inquiry. Humanists avidly read history, taught it to their young, and, perhaps most important, wrote it themselves. They were confident that proper historical method, by extending across time their grasp of human reality, would enhance their active role in the present. For Machiavelli, who avowed to present people as they were and not as they ought to be, history would become the basis of a new political science. Similarly, direct experience took precedence over traditional wisdom. Francesco Guicciardini (1483–1540) later echoed the dictum of Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72), that an essential form of wisdom could be found only “at the public marketplace, in the theatre, and in people’s homes”:

I, for my part, know no greater pleasure than listening to an old man of uncommon prudence speaking of public and political matters that he has not learnt from books of philosophers but from experience and action; for the latter are the only genuine methods of learning anything.

Renaissance realism also involved the unblinking examination of human uncertainty, folly, and immorality. Petrarch’s honest investigation of his own doubts and mixed motives is born of the same impulse that led Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–75) to conduct in the Decameron (1348–53) an encyclopaedic survey of human vices and disorders. Similarly critical treatments of society from a humanistic perspective would be produced later by Erasmus, Thomas More (1478–1535), Baldassare Castiglione (1478–1529), François Rabelais (c. 1494–1553), and Michel de Montaigne (1533–92). But it was typical of humanism that this moral criticism did not, conversely, postulate an ideal of absolute purity. Humanists asserted the dignity of normal earthly activities and even endorsed the pursuit of fame and the acquisition of wealth. The emphasis on a mature and healthy balance between mind and body, first implicit in Boccaccio, is evident in the work of Giannozzo Manetti, Francesco Filelfo (1398–1481), and Paracelsus (1493–1541) and eloquently embodied in Montaigne’s final essay, “Of Experience.” Humanistic tradition, rather than revolutionary inspiration, eventually led Francis Bacon to assert that the passions should become objects of systematic investigation. The realism of the humanists was, finally, brought to bear on the Roman Catholic Church, which they called into question not as a theological structure but as a political institution. Here as elsewhere, however, the intention was neither radical nor destructive. Humanism did not aim to remake humanity but rather aimed to reform social order through an understanding of what was basically and inalienably human.

CRITICAL SCRUTINY AND CONCERN WITH DETAIL

Humanistic realism bespoke a comprehensively critical attitude. Indeed, the productions of early humanism constituted a manifesto of independence, at least in the secular world, from all preconceptions and all inherited programs. The same critical self-reliance shown by Salutati in his textual emendations and Boccaccio in his interpretations of myth was evident in almost the whole range of humanistic endeavour. It was cognate with a new specificity, a pro...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Philosophy in the Renaissance

- Chapter 2: Early Modern Philosophy

- Chapter 3: Philosophy in the Enlightenment

- Chapter 4: The 19th Century

- Chapter 5: Contemporary Philosophy

- Glossary

- Bibliogrphy

- Index