- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Native American Culture

About this book

Even as contact with European cultures eroded indigenous lifestyles across North America, many Native American groups found ways to preserve the integrity of their communities through the arts, customs, languages, and religious traditions that animate Native American life. While their collective struggles against a common cause may create the semblance of a shared past, each Native American community has a unique heritage that reflects a singular history. The ancient cultural legacies that both distinguish and unite these diverse tribes are the subject of this engrossing volume.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Native American Culture by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kathleen Kuiper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

OVERVIEW

For many years the American Indians of both the United States and Canada were perceived as vanishing peoples—unfortunate, but inevitable, victims of Western civilization’s march toward perfection. Today this sense of their teetering on the brink of cultural or physical extinction has largely disappeared. In fact, many members of U.S. Indian tribes and Canada’s First Nations actively engage in cultural nurturing and revitalization, including new emphasis on tribal government, identification of stable sources for group economic well-being, and encouragement of the use of indigenous languages. There is also increased concern about the preservation of sacred sites and the repatriation of sacred objects.

NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN HERITAGE

The date of the arrival in North America of the initial wave of peoples from whom the American Indians (or Native Americans) emerged is still a matter of considerable uncertainty. It is relatively certain that they were Asiatic peoples who originated in northeastern Siberia and crossed the Bering Strait (perhaps when it was a land bridge) into Alaska and then gradually dispersed throughout the Americas. The glaciations of the Pleistocene Epoch (1.6 million to 10,000 years ago) coincided with the evolution of modern humans, and ice sheets blocked ingress into North America for extended periods of time. It was only during the interglacial periods that people ventured into this unpopulated land. Some scholars claim an arrival before the last (Wisconsin) glacial advance, about 60,000 years ago. The latest possible date now seems to be 20,000 years ago, with some pioneers filtering in during a recession in the Wisconsin glaciation.

These prehistoric invaders were Stone Age hunters who led a nomadic life, a pattern that many retained until the coming of Europeans. As they worked their way southward from a narrow, ice-free corridor in what is now the state of Alaska into the broad expanse of the continent—between what are now Florida and California—the various communities tended to fan out, hunting and foraging in comparative isolation. Until they converged in the narrows of southern Mexico and the confined spaces of Central America, there was little of the fierce competition or the close interaction among groups that might have stimulated cultural inventiveness.

The size of the pre-Columbian aboriginal population of North America remains uncertain, since the widely divergent estimates have been based on inadequate data. The pre-Columbian population of what is now the United States and Canada, with its more widely scattered societies, has been variously estimated at somewhere between 600,000 and 2 million. By that time, the Indians there had not yet adopted intensive agriculture or an urban way of life, although the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash supplemented hunting and fishing throughout the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys and in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence river region, as well as along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coastal Plain. In those areas, semisedentary peoples had established villages, and among the Iroquois and the Cherokee, powerful federations of tribes had been formed. Elsewhere, however, on the Great Plains, the Canadian Shield, the northern Appalachians, the Cordilleras, the Great Basin, and the Pacific Coast, hunting, fishing, and gathering constituted the basic economic activity; and, in most instances, extensive territories were needed to feed and support small groups.

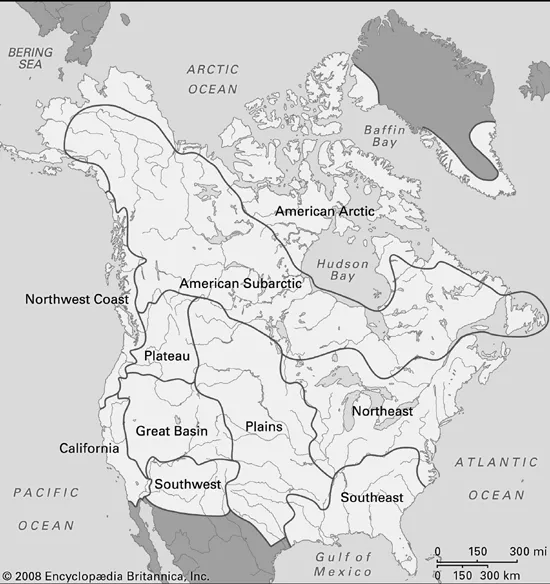

Culture areas of North American Indians.

The history of the entire aboriginal population of North America after the Spanish conquest has been one of unmitigated tragedy. The combination of susceptibility to Old World diseases, loss of land, and the disruption of cultural and economic patterns caused a drastic reduction in numbers—indeed, the extinction of many communities. It is only since about 1900 that the numbers of some Indian peoples have begun to rebound.

NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURE AREAS

Comparative studies are an essential component of all scholarly analyses, whether the topic under study is human society, fine art, paleontology, or chemistry. The similarities and differences found in the entities under consideration help to organize and direct research programs and exegeses. The comparative study of cultures falls largely in the domain of anthropology, which often uses a typology known as the culture area approach to organize comparisons across cultures.

The culture area approach was delineated at the turn of the 20th century and continued to frame discussions of peoples and cultures into the 21st century. A culture area is a geographic region where certain cultural traits have generally co-occurred. For instance, in North America between the 16th and 19th centuries, the Northwest Coast Native American culture area was characterized by traits such as salmon fishing, woodworking, large villages or towns, and hierarchical social organization.

The specific number of culture areas delineated for Native America has been somewhat variable because regions are sometimes subdivided or conjoined. The 10 culture areas discussed in this volume are among the most commonly used—the Arctic, the subarctic, the Northeast, the Southeast, the Plains, the Southwest, the Great Basin, California, the Northwest Coast, and the Plateau. Notably, some scholars prefer to combine the Northeast and Southeast into one Eastern Woodlands culture area, or the Plateau and Great Basin into a single Intermontane culture area. Discussion of each culture area considers the location, climate, environment, languages, tribes, and common cultural characteristics of the area before it was heavily colonized.

CHAPTER 2

THE AMERICAN ARCTIC AND SUBARCTIC CULTURES

The three major environmental zones of forest, tundra, and coast, and the transitions between them, establish the range of conditions to which the ways of life of the circumpolar peoples are adapted. Broadly speaking, four types of adaptation are found. The first is entirely confined within the forest and is based on the exploitation of its fairly diverse resources of land animals, birds, and fish. Local groups tend to be small and widely scattered, each exploiting a range of territory around a fixed, central location.

The second kind of adaptation spans the transition between forest and tundra. It is characterized by a heavy, year-round dependence on herds of reindeer or caribou, whose annual migrations from the forest to the tundra in spring and from the tundra back to the forest in autumn are matched by the lengthy nomadic movements of the associated human groups. In North America, these are hunters, who aim to intercept the herds on their migrations, rather than herders, as in Eurasia.

The third kind of adaptation, most common among Inuit (Eskimo) groups, involves a seasonal movement in the reverse direction, between the hunting of sea mammals on the coast in winter and spring and the hunting of caribou and fishing on the inland tundra in summer and autumn.

Fourth, typical of cultures of the northern Pacific coast is an exclusively maritime adaptation. People live year-round in relatively large, coastal settlements, hunting the rich resources of marine mammals from boats in summer and from the ice in winter.

In northern North America the forest and forest-tundra modes of subsistence are practiced only by Indian peoples, while coastal and coastal-tundra adaptations are the exclusive preserve of the Inuit and of the Aleut of the northern Pacific islands. Indian cultures are thus essentially tied to the forest, whereas Inuit and Aleut cultures are entirely independent of the forest and tied rather to the coast. Conventionally, this contrast has been taken to mark the distinction between peoples of the subarctic and those of the Arctic.

PEOPLES OF THE AMERICAN ARCTIC

Scholarly custom separates the American Arctic peoples from other American Indians, from whom they are distinguished by various linguistic, physiological, and cultural differences. Because of their close social, genetic, and linguistic relations to Yupik speakers in Alaska, the Yupik-speaking peoples living near the Bering Sea in Siberia are sometimes discussed with these groups.

LINGUISTIC COMPOSITION

Various outside relationships for the Eskimo-Aleut language stock have been suggested, but in the absence of conclusive evidence the stock must be considered to be isolated. Internally, it falls into two related divisions, Eskimo and Aleut.

The Eskimo division is further subdivided into Inuit and Yupik. Inuit, or Eastern Eskimo (in Greenland called Greenlandic or Kalaaleq; in Canada, Inuktitut; in Alaska, Inupiaq), is a single language formed of a series of intergrading dialects that extend thousands of miles, from eastern Greenland to northern Alaska and around the Seward Peninsula to Norton Sound; there it adjoins Yupik, or Western Eskimo. The Yupik section, on the other hand, consists of five separate languages that were not mutually intelligible. Three of these are Siberian: Sirenikski is now virtually extinct, Naukanski is restricted to the easternmost Chukchi Peninsula, and Chaplinski is spoken on Alaska’s St. Lawrence Island, on the southern end of the Chukchi Peninsula, and near the mouth of the Anadyr River in the south and on Wrangel Island in the north. In Alaska, Central Alaskan Yupik includes dialects that covered the Bering Sea coast from Norton Sound to the Alaska Peninsula, where it met Pacific Yupik (known also as Sugpiaq or Alutiiq). Pacific Yupik comprises three dialects: that of the Kodiak Island group, that of the south shore of the Kenai Peninsula, and that of Prince William Sound.

Aleut now includes only a single language of two dialects. Yet before the disruption that followed the 18th-century arrival of Russian fur hunters, it included several dialects, if not separate languages, spoken from about longitude 158° W on the Alaska Peninsula, throughout the Aleutian Islands, and westward to Attu, the westernmost island of the Aleutian chain. The Russians transplanted some Aleuts to formerly unoccupied islands of the Commander group, west of the Aleutians, and to those of the Pribilofs, in the Bering Sea.

ETHNIC GROUPS

In general, American Eskimo peoples did not organize their societies into units such as clans or tribes. Identification of group membership was traditionally made by place of residence, with the suffix -miut (“people of”) applied in a nesting set of labels to people of any specifiable place—from the home of a family or two to a broad region with many residents. Among the largest of the customary -miut designators are those coinciding at least roughly with the limits of a dialect or subdialect, the speakers of which tended to seek spouses from within that group; such groups might range in size from 200 to as many as 1,000 people.

Historically, each individual’s identity was defined on the basis of connections such as kinship and marriage in addition to place and language. All of these continued to be important to Arctic self-identity in the 20th and 21st centuries, although native peoples in the region have also formed large—and in some cases pan-Arctic—organizations in order to facilitate their representation in legal and political affairs.

Ethnographies, historical accounts, and documents from before the late 20th century typically used geographic nomenclature to refer to groups that shared similar dialects, customs, and material cultures. For instance, in reference to groups residing on the North Atlantic and Arctic coasts, these texts might discuss the East Greenland Eskimo, West Greenland Eskimo, and Polar Eskimo, although only the last territorial division corresponded to a single self-contained, in-marrying (endogamous) group. The peoples of Canada’s North Atlantic and eastern Hudson Bay were referred to as the Labrador Eskimo and the Eskimo of Quebec. These were often described as whole units, although each comprises a number of separate societies. The Baffinland Eskimo were often included in the Central Eskimo, a grouping that otherwise included the Caribou Eskimo of the barrens west of Hudson Bay and the Iglulik, Netsilik, Copper, and Mackenzie Eskimo, all of whom live on or near the Arctic Ocean in northern Canada. The Mackenzie Eskimo, however, are also set apart from other Canadians as speakers of the western, or Inupiaq, dialect of the Inuit (Eastern Eskimo) language. Descriptions of these Alaskan Arctic peoples have tended to be along linguistic rather than geographic lines and include the Inupiaq-speaking Inupiat, who live on or near the Arctic Ocean and as far south as the Bering Strait. All of the groups noted thus far reside near open water that freezes solid in winter, speak dialects of the Inuit language, and are commonly referred to in aggregate as Inuit (meaning “the people”).

The other American Arctic groups live farther south, where open water is less likely to freeze solid for greatly extended periods. The Bering Sea Eskimo and St. Lawrence Island Eskimo live around the Bering Sea, where resources include migrating sea mammals and, in the mainland rivers, seasonal runs of salmon and other fish. The Pacific Eskimo, on the other hand, live on the shores of the North Pacific itself, around Kodiak Island and Prince William Sound, where the Alaska Current prevents open water from freezing at all. Each of these three groups speaks a distinct form of Yupik; together they are commonly referred to as Yupik Eskimo or as Yupiit (“the people”).

In the Gulf of Alaska, ethnic distinctions were blurred by Russian colonizers who used the term Aleut to refer not only to people of the Aleutian Islands but also to the culturally distinct groups residing on Kodiak Island and the neighbouring areas of the mainland. As a result, many modern native people from Kodiak, the Alaska Peninsula, and Prince William Sound identify themselves as Aleuts, although only those from the tip of the peninsula and the Aleutian Islands are descended from people who spoke what linguists refer to as the Aleut language; these latter refer to themselves as Unangan (“people”). The groups from Kodiak Island and the neighbouring areas traditionally spoke the form of Yupik called Pacific Yupik, Sugpiaq, or Alutiiq and refer to themselves as Alutiiq (singular) or Alutiit (plural).

TRADITIONAL CULTURE

The traditional cultures of the Arctic are generally discussed in terms of two broad divisions: seasonally migratory peoples living on or near winter-frozen coastlines (the northern Yupiit and the Inuit) and more-sedentary groups living on or near the open-water regions of the Pacific coast (the southern Yupiit and Aleuts).

SEASONALLY MIGRATORY PEO...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Overview

- Chapter 2: The American Arctic and Subarctic Cultures

- Chapter 3: Northwest Coast and California Culture Areas

- Chapter 4: Plateau and Great Basin Culture Areas

- Chapter 5: Southwest and Plains Culture Areas

- Chapter 6: Northeast and Southeast Culture Areas

- Chapter 7: Native American Art

- Chapter 8: Native American Music

- Chapter 9: Native American Dance

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index