eBook - ePub

Pre-Columbian America

Empires of the New World

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From the Mayan calendar to the Toltec architecture at Chichén Itzá, the bequests of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations have endured long after the societies that created them declined. The intellectual and cultural achievements of Pre-Columbian America rivaled those of ancient Rome and Egypt, and greatly enriched the landscape of present-day Mexico and Central America. The traditions, social organizations, languages, and ideas that shaped each of these cultures are examined in this fascinating volume.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pre-Columbian America by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kathleen Kuiper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

MESOAMERICAN CIVILIZATIONS

Mesoamerica is a term that applies to the area of Mexico and Central America that was civilized in pre-Spanish times. In many respects, the American Indians who inhabited Mesoamerica were the most advanced native peoples in the Western Hemisphere. The northern border of Mesoamerica runs west from a point on the Gulf Coast of Mexico above the modern port of Tampico, then dips south to exclude much of the central desert of highland Mexico, meeting the Pacific coast opposite the tip of Baja (Lower) California. On the southeast, the boundary extends from northwestern Honduras on the Caribbean across to the Pacific shore in El Salvador. Thus, about half of Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador are included in Mesoamerica.

Geographically and culturally, Mesoamerica consists of two strongly contrasted regions: highland and lowland. The Mexican highlands are formed mainly by the two Sierra Madre ranges that sweep down on the east and west. Lying athwart them is a volcanic cordillera stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The high valleys and landlocked basins of Mexico were important centres of pre-Spanish civilization. In the southeastern part of Mesoamerica lie the partly volcanic Chiapas–Guatemala highlands. The lowlands are primarily coastal. Particularly important was the littoral plain extending south along the Gulf of Mexico, expanding to include the Petén-Yucatán Peninsula, homeland of the Mayan peoples.

Agriculture in Mesoamerica was advanced and complex. A great many crops were planted, of which corn, beans, and squashes were among the most important. In the highlands, hoe cultivation of more or less permanent fields was the rule, with such intensive forms of agriculture as irrigation and chinampas (the so-called floating gardens reclaimed from lakes or ponds) practiced in some regions. In contrast, lowland agriculture was frequently of the shifting variety. A patch of jungle was first selected, felled and burned toward the end of the dry season, and then planted with a digging stick in time for the first rains. After a few years of planting, the field was abandoned to the forest, as competition from weeds and declining soil fertility resulted in diminishing yields.

There is good evidence, however, that the slash-and-burn system of cultivation was often supplemented by “raised-field” cultivation in the lowlands. These artificially constructed earthen hillocks built in shallow lakes or marshy areas were not unlike the chinampas of the Mexican highlands. In addition, terraces were constructed and employed for farming in some lowland regions. Nevertheless, the demographic potential for agriculture was probably always greater in the highlands than it was in the lowlands, and this was demonstrated in the more extensive urban developments in the former area.

The extreme diversity of the Mesoamerican environment produced what has been called symbiosis among its subregions. Interregional exchange of agricultural products, luxury items, and other commodities led to the development of large and well-regulated markets in which cacao beans were used for money. It may have also led to large-scale political unity and even to states and empires. High agricultural productivity resulted in a nonfarming class of artisans who were responsible for an advanced stone architecture, featuring the construction of stepped pyramids, and for highly evolved styles of sculpture, pottery, and painting.

The Mesoamerican system of thought, recorded in folding-screen books of deerskin or bark paper, was perhaps of even greater importance in setting them off from other New World peoples. This system was ultimately based upon a calendar in which a ritual cycle of 260 (13 × 20) days intermeshed with a “vague year” of 365 days (18 × 20 days, plus five “nameless” days), producing a 52-year Calendar Round. Religious life was geared to this cycle, which is unique to them. The Mesoamerican pantheon was associated with the calendar and featured an old, dual creator god; a god of royal descent and warfare; a sun god and moon goddess; a rain god; a culture hero called the Feathered Serpent; and many other deities. Also characteristic was a layered system of 13 heavens and nine underworlds, each with its presiding god. Much of the system was under the control of a priesthood that also maintained an advanced knowledge of astronomy.

As many as 14 language families were found in Mesoamerica. Nahuatl, the official tongue of the Aztec empire, was the most important of these. Another large family is Mayan, with a number of mutually unintelligible languages, at least some of which were spoken by the inhabitants of the great Maya ceremonial centres. The other languages that played a great part in Mesoamerican civilization were Mixtec and Zapotec, both of which had large, powerful kingdoms at the time of the Spanish conquest. Still a linguistic puzzle are such languages as Tarascan, mother tongue of an “empire” in western Mexico that successfully resisted Aztec encroachments. It has no sure relatives, although some linguistic authorities have linked it with the Quechua language of distant Peru.

EARLY HUNTERS (TO 6500 BC)

The time of the first peopling of Mesoamerica remains a puzzle, as it does for that of the New World in general. It is widely accepted that groups of peoples entered the hemisphere from northeastern Siberia, perhaps by a land bridge that then existed, at some time in the Late Pleistocene, or Ice Age. There is abundant evidence that, by 11,000 BC, hunting peoples had occupied most of the New World south of the glacial ice cap covering northern North America. These peoples hunted such large grazing mammals as mammoth, mastodon, horse, and camel, armed with spears to which were attached finely made, bifacially chipped points of stone. Finds in Mesoamerica, however, confirm the existence of a “prebifacial-point horizon,” a stage known to have existed elsewhere in the Americas, and suggest that it is of very great age. In 1967 archaeologists working at the site of Tlapacoya, southeast of Mexico City, uncovered a well-made blade of obsidian associated with a radiocarbon date of about 21,000 BC. Near Puebla, Mexico, excavations in the Valsequillo region revealed cultural remains of human groups that were hunting mammoth and other extinct animals, along with unifacially worked points, scrapers, perforators, burins, and knives. A date of about 21,800 BC has been suggested for the Valsequillo finds.

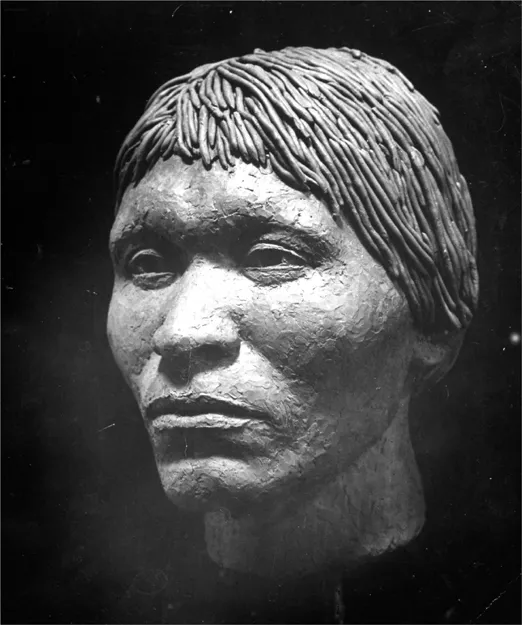

More substantial information on Late Pleistocene occupations of Mesoamerica comes from excavations near Tepexpan, northeast of Mexico City. The excavated skeletons of two mammoths showed that these beasts had been killed with spears fitted with lancelike stone points and butchered on the spot. A possible date of about 8000 BC has been suggested for the two mammoth kills. In the same geologic layer as the slaughtered mammoths was found a human skeleton; this Tepexpan “man” has been shown to be female and rather a typical American Indian of modern form. While the association with the mammoths was first questioned, fluorine tests have proved them to be contemporary.

A casting made from the remains of a human female found in Tepexpan, near Mexico City. An initial mistake in gender attribution led to the remains being erroneously labeled “Tepexpan man.” Francis Miller/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

The environment of these earliest Mesoamericans was quite different from that existing today, for volcanoes were then extremely active, covering thousands of square miles with ashes. Temperatures were substantially lower, and local glaciers formed on the highest peaks. Conditions were ideal for the large herds of grazing mammals that roamed Mesoamerica, especially in the highland valleys, much of which consisted of cool, wet grasslands not unlike the plains of the northern United States. All of this changed around 7000 BC, when worldwide temperatures rose and the great ice sheets of northern latitudes began their final retreat. This brought to an end the successful hunting way of life that had been followed by Mesoamericans, although man probably also played a role in bringing about the extinction of the large game animals.

INCIPIENT AGRICULTURE (6500–1500 BC)

The most crucial event in the prehistory of Mesoamerica was man’s capture of the food energy contained in plants. This process centred on three plants: Indian corn (maize), beans, and squashes. Since about 90 percent of all food calories in the diet of Mesoamericans eventually came from corn, archaeologists for a long time have sought the origins of this plant—which has no wild forms existing today—in order to throw light on the agricultural basis of Mesoamerican civilization.

The search for Mesoamerican agricultural origins has been carried forward most successfully through excavations in dry caves and rock shelters in the modern southern Mexican states of Puebla and Oaxaca. Sequences from these archaeological sites show a gradual transition from the Early Hunting to the Incipient Cultivation periods. At the Guila Naquitz cave, in Oaxaca, there are indications that the transition began as early as 8900 BC. Finds from caves in the Tehuacán valley of Puebla, however, offer more substantial evidence of the beginnings of plant domestication at a somewhat later time. There, the preservation of plant remains is remarkably good, and from these it is evident that shortly after 6500 BC the inhabitants of the valley were selecting and planting seeds of chili peppers, cotton, and one kind of squash. Most important, between 5000 and 3500 BC they were beginning to plant mutant forms of corn that already were showing signs of the husks characteristic of domestic corn.

One of the problems complicating this question of the beginnings of early corn cultivation is related to a debate between paleobotanists on wild versus domesticated strains. One school of thought holds that the domesticated races of the plant developed from a wild ancestor. The other opinion is that there was never such a thing as wild corn, that instead corn (Zea mays) developed from a related grass, teosinte (Zea mexicana or Euchlaena mexicana). In any event, by 5000 BC corn was present and being used as a food, and between 2,000 and 3,000 years after that it had developed rapidly as a food plant. It has been estimated that there is more energy present in a single kernel of some modern races than there was in an ear of this ancient Tehuacán corn. Possibly some of this was popped, but a new element in food preparation is seen in the metates (querns) and manos (handstones) that were used to grind the corn into meal or dough.

Beans appeared after 3500 BC, along with a much improved race of corn. This enormous increase in the amount of plant food available was accompanied by a remarkable shift in settlement pattern. In place of the temporary hunting camps and rock shelters, which were occupied only seasonally by small bands, semi permanent villages of pit houses were constructed on the valley floor. Increasing sedentariness is also to be seen in the remarkable bowls and globular jars painstakingly pecked from stone, for pottery was as yet unknown in Mesoamerica.

In the centuries between 3500 and 1500 BC, plant domestication began in what had been hunting-gathering contexts, as on the Pacific coast of Chiapas and on the Veracruz Gulf coast and in some lacustrine settings in the Valley of Mexico. It seems probable that early domesticated plants from such places as the Tehuacán valley were carried to these new environmental niches. In many cases, this shift of habitat resulted in genetic improvements in the food plants.

Pottery, which is a good index to the degree of permanence of a settlement (because of its fragility it is difficult to transport), was made in the Tehuacán valley by 2300 BC. Fired clay vessels were made as early as 4000 BC in Ecuador and Colombia, and it is probable that the idea of their manufacture gradually diffused north to the increasingly sedentary peoples of Mesoamerica.

The picture, then, is one of man’s growing control over his environment through the domestication of plants. Animals played a very minor role in this process, with only the dog being surely domesticated before 1500 BC. At any rate, by 1500 BC the stage was set for the adoption of a fully settled life, with many of the sedentary arts already present. The final step was taken only when native agriculture in certain especially favoured subregions became sufficiently effective to allow year-round settlement of villages.

EARLY FORMATIVE PERIOD (1500–900 BC)

It is fairly clear that the Mexican highlands were far too dry during the much warmer interval that prevailed from 5000 to 1500 BC for agriculture to supply more than half of a given population’s energy needs. This was not the case along the alluvial lowlands of southern Mesoamerica, and it is no accident that the best evidence for the earliest permanent villages in Mesoamerica comes from the Pacific littoral of Chiapas (Mexico) and Guatemala, although comparable settlements also have been reported from both the Maya lowlands (Belize) and the Veracruz Gulf coast.

EARLY VILLAGE LIFE

The Barra (c. 1800–1500 BC), Ocós (1500–1200 BC), and Cuadros (1100–900 BC) phases of the Pacific coasts of Chiapas and Guatemala are good examples of early village cultures. The Barra phase appears to have been transitional from earlier preagricultural phases and may not have been primarily dependent upon corn farming, but people of the Ocós and Cuadros phases raised a small-eared corn known as nal-tel, which was ground on metates and manos and cooked in globular jars. From the rich lagoons and estuaries in this area, the villagers obtained shellfish, crabs, fish, and turtles. Their villages were small, with perhaps 10 to 12 thatched-roof houses arranged haphazardly.

Ocós pottery is highly developed technically and artistically. Something of the mental life of the times may be seen in the tiny, handmade clay figurines produced by the Ocós villagers. These, as in Formative cultures generally throughout Mesoamerica, represent nude females and may have had something to do with a fertility cult. The idea of the temple-pyramid may well have taken root by that time, for one Ocós site has produced an earthen mound about 26 feet (8 metres) high that must have supported a perishable building. The implication of the site is that, with increasing prosperity, some differentiation of a ruling class had taken place, for among the later Mesoamericans the ultimate function of a pyramid was as a final resting place for a great leader.

Eventually, effective village farming with nucleated...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Mesoamerican Civilizations

- Chapter 2: The Maya: Classic Period

- Chapter 3: The Toltec and the Aztec, Post-Classic Period (900–1519)

- Chapter 4: Andean Civilization

- Chapter 5: The Inca

- Appendix: Selected Gods of the New World

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index