- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From lemurs to apes to human beings, primates are unique among mammals—for example, our brains are large compared to our size. Our complex interactions, intricate social structures, and extensive range of emotions allow us to adapt and thrive in diverse habitats around the globe. In this volume, readers are invited into the many domains of these extraordinary creatures to discover the incredible diversity of primate species. Readers will also learn about the long history of human beings, from our earliest ancestors, the australopiths, to the homo sapiens of today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE GENERAL FEATURES OF PRIMATES

In zoology, a primate is any mammal from the group that includes the lemurs, lorises, tarsiers, monkeys, apes, and humans. The order Primates, with its 300 or more species, is the third most diverse order of mammals, after rodents (Rodentia) and bats (Chiroptera). Although there are some notable variations between some primate groups, they share several anatomic and functional characteristics reflective of their common ancestry. When compared with body weight, the primate brain is larger than that of other terrestrial mammals, and it has a fissure unique to primates called the Calcarine sulcus that separates the first and second visual areas on each side of the brain. Whereas all other mammals have claws or hooves on their digits, only primates have flat nails. Some primates do have claws, but even among these there is a flat nail on the big toe (hallux). In all primates except humans, the hallux diverges from the other toes and together with them forms a pincer capable of grasping objects such as branches. Not all primates have similarly dextrous hands; only the catarrhines (Old World monkeys, apes, and humans) and a few of the lemurs and lorises have an opposable thumb. Primates are not alone in having grasping feet, but as these occur in many other arboreal mammals (e.g., squirrels and opossums), and as most present-day primates are arboreal, this characteristic suggests that they evolved from an ancestor that was arboreal. So too does primates’ possession of specialized nerve endings (Meissner’s corpuscles) in the hands and feet that increase tactile sensitivity. As far as is known, no other placental mammal has them. Primates possess dermatoglyphics (the skin ridges responsible for fingerprints), but so do many other arboreal mammals. The eyes face forward in all primates so that the eyes’ visual fields overlap. Again, this feature is not by any means restricted to primates, but it is a general feature seen among predators. It has been proposed, therefore, that the ancestor of the primates was a predator, perhaps insectivorous. The optic fibres in almost all mammals cross over (decussate) so that signals from one eye are interpreted on the opposite side of the brain, but, in some primate species, up to 40 percent of the nerve fibres do not cross over. Primate teeth are distinguishable from those of other mammals by the low, rounded form of the molar and premolar cusps, which contrast with the high, pointed cusps or elaborate ridges of other placental mammals. This distinction makes fossilized primate teeth easy to recognize. Fossils of the earliest primates date to the Early Eocene Epoch (56 million to 40 million years ago) or perhaps to the Late Paleocene Epoch (59 million to 56 million years ago). Though they began as an arboreal group, and many (especially the platyrrhines, or New World monkeys) have remained thoroughly arboreal, many have become at least partly terrestrial, and many have achieved high levels of intelligence.

SIZE RANGE AND ADAPTIVE DIVERSITY

Members of the order Primates show a remarkable range of size and adaptive diversity. The smallest primate is Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur (Microcebus berthae) of Madagascar, which weighs some 35 grams (one ounce); the most massive is certainly the gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), whose weight may be more than 4,000 times as great, varying from 140 to 180 kg (about 300 to 400 pounds).

Primates occupy two major vegetational zones: tropical forest and woodland-grassland vegetational complexes. Each of these zones has produced in its resident primates the appropriate adaptations, but there is perhaps more diversity of bodily form among forest-living species than among savanna inhabitants. One of the explanations of this difference is that it is the precise pattern of locomotion rather than the simple matter of habitat that governs overt bodily adaptations. Within the forest there are a number of ways of moving about. An animal can live on the forest floor or in the canopy, for instance, and within the canopy it can move in three particular ways: (a) by leaping—a function principally dictated by the hind limbs; (b) by arm swinging (brachiation)—a function particularly of the forelimbs; (c) by a type of movement known as quadrupedalism, in which function is equally divided between the forelimbs and the hind limbs. On the savanna, or in the woodland-savanna biome, which substantially demands adaptations for ground-living locomotion rather than those for tree-living, the possibilities are limited. If bipedal humans are discounted, there is a single pattern of ground-living locomotion, which is called quadrupedalism. Within this category there are at least two variations on the theme: (a) knuckle-walking quadrupedalism, and (b) digitigrade quadrupedalism. The former gait is characteristic of the African apes (chimpanzee and gorilla), and the latter of baboons and macaques, which walk on the flats of their fingers. After human beings, Old World monkeys of the subfamily Cercopithecinae are the most successful colonizers of nonarboreal habitats.

The structural adaptations of primates resulting from locomotor differences are considered in more detail in the section Locomotion, but they do not prove to be very extensive. Primates are a homogeneous group morphologically, and it is only in the realm of behaviour that differences between primate taxa are clearly discriminant. It can be said that the most successful primates (judged in terms of the usual criteria of population numbers and territorial spread) are those that have departed least from the ancestral pattern of structure but farthest from the ancestral pattern of behaviour. “Manners makyth man” is true in the widest sense of the word; in the same sense, manners delineate primate species.

DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE

The nonhuman primates have a wide distribution throughout the tropical latitudes of Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and South America. Within this tropical belt, which lies between latitudes 25° N and 30° S, they have a considerable vertical range. In Ethiopia the gelada (genus Theropithecus) is found living at elevations up to 5,000 metres (16,000 feet). Gorillas of the Virunga Mountains are known to travel across mountain passes at altitudes of more than 4,200 metres (about 13,800 feet) when traveling from one high valley to another. The howler monkeys of Venezuela (Alouatta seniculus) live at 2,500 metres (8,200 feet) in the Cordillera de Merida, and in northern Colombia the durukuli (genus Aotus) is found in the tropical montane forests of the Cordillera Central.

In habitat, primates are predominantly tropical, but few species of nonhuman primates extend their ranges well outside the tropics. The so-called Barbary “ape” (Macaca sylvanus)—actually a monkey—lives in the temperate forests of the Atlas and other mountain ranges of Morocco and Algeria. Some populations of rhesus monkey (M. mulatta) extended until the middle of the 20th century to the latitude of Beijing in northern China, and the Tibetan macaque (M. thibetana) is found from the warm coastal ranges of Fujian (Fukien) province to the cold mountains of Sichuan (Szechwan). One of the most remarkable, however, is the Japanese macaque (M. fuscata), which in the north of Honshu lives in mountains that are snow-covered for eight months of the year; some populations have learned to make life more tolerable for themselves by spending most of the day in the hot springs that bubble out and form pools in volcanic areas. Finally, two western Chinese species of snub-nosed monkey, the golden (Rhinopithecus roxellana) and black (R. bieti), are confined to high altitudes (up to 3,000 metres [about 9,800 feet] in the case of the former and to 4,500 metres [about 14,800 feet] in the latter), where the temperature drops below 0° C (32° F) every night and often barely rises above it by day.

Although many primates are still plentiful in the wild, the numbers of many species are declining steeply. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), more than 70 percent of primates in Asia and roughly 40 percent of primates in South America, in mainland Africa, and on the island of Madagascar are listed as endangered. A number of species, particularly the orangutan, the gorilla, some of the Madagascan lemurs, and some South American species, are in serious danger of extinction unless their habitats can be preserved in perpetuity and human predation kept under control. The populations of several species number only in the hundreds, and in 2000 a subspecies of African red colobus monkey (Procolobus badius) became the first primate since 1800 to be declared extinct.

Red-bellied lemur (Eulemur rubriventer) in the eastern Madagascar rainforest near Ranomafana. (Top) © David Curl/Oxford Scientific Films Ltd.

In the midst of these declines, the populations of some critically endangered primate species have increased. Concerted efforts to breed a type of marmoset, the golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia), in captivity have been successful; this species’s reintroduction to the wild continues in Brazil. The estimated number of western lowland gorillas (G. gorilla gorilla), a species thought to be critically endangered, increased when a population of more than 100,000 was discovered in 2008 in the swamps of the Lac Télé Community Reserve in the Republic of the Congo.

NATURAL HISTORY OF PRIMATES

The natural history of primates varies among the different groups. For example, some primates may be restricted to a particular breeding season, whereas others are able to breed throughout the year. Gestational periods range from 54 to 68 days in mouse lemurs to roughly 267 days in humans. Longevity and growth are also type dependent, with apes possessing the longest primate life spans. Such variability also extends to methods of locomotion, diet, and preferred habitat.

REPRODUCTION AND LIFE CYCLE

The stages of the life cycle of primates vary considerably in duration. Among the most primitive members of the group, these stages are broadly comparable to those of other mammals of similar size. Higher in the phylogenetic scale, they are substantially extended. The greatest difference is in the duration of the infant and juvenile stages combined; the least is in the gestation period, which, despite the general belief, cannot be consistently correlated with adult body size. Gibbons, which weigh considerably less than macaques, have a 20 percent longer gestation period.

The clear trend toward prolongation of the period of juvenile and adolescent life is probably to be associated with the corresponding trend toward a progressive elaboration of the brain. The extended period of adolescence means that the young remain under adult (primarily maternal) surveillance for a long period, during which time the juvenile acquires, by example from its mother and peers, the knowledge that will allow it to become properly integrated as a fully adult member of a complicated social system. One might therefore expect a close correlation between the period of adolescence, the brain size, and the complexity of the social system; and, insofar as the latter factor can be assessed, this appears to be the case.

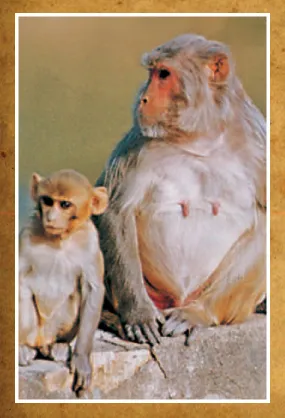

Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Ylla—Rapho/Photo Researchers

BREEDING PERIODS

The reproductive events in the primate calendar are copulation, gestation, birth, and lactation. Owing to the long duration of the gestation period, these phases occupy the female primate (among higher primates anyway) for a full year or more; then the cycle starts again. The female does not usually come into physiological receptivity until the infant of the previous pregnancy has been weaned.

Most lemurs and lorises show one or more discrete breeding seasons during the year, during which time they may undergo more than one reproductive estrous cycle (i.e., period of sexual activity). The breeding seasons are separated by periods of anestrus, which in bush babies and mouse lemurs are accompanied by changes in the skin of the external genitalia (vulva), which closes over, completely sealing the vagina. When living in the wild in the Sudan, the lesser bush baby (Galago senegalensis) has an estrus that occurs only twice yearly, during December and August. In captivity, however, breeding seasons may occur at any period in the year. In the wild, birth seasons are closely correlated with the prevailing climate, but in captivity under equable laboratory conditions, this consideration does not apply. For instance, in its native Madagascar, the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) has only a single breeding season during the year, conception occurring in autumn (April) and births taking place in late winter (August and September). However, in zoos in the Northern Hemisphere, a seasonal inversion occurs in which the birth period shifts to late spring and early summer. These examples indicate the influence of environmental factors on the timing of the birth seasons.

Reproductive cycles in tarsiers, apes, and many monkeys continue uninterrupted throughout the year, though seasonality in births is characteristic mainly of monkey species living either outside the equatorial belt (5° north and south of the Equator) or at high elevations in equatorial regions, where dry seasons and seasonal food shortages occur. Seasonality of births in macaques (genus Macaca species) has been documented in Japan, on Cayo Santiago in the Caribbean (where an introduced population thrives under seminatural conditions), and in India. Observations of langurs in India and Sri Lanka, of geladas in Ethiopia, and of patas monkeys in Uganda have also demonstrated seasonality in areas with well-marked wet and dry seasons. Those within the equatorial belt tend to display birth peaks rather than birth seasons. A birth peak is a period of the year in which a high proportion of births, but not by any means all, are concentrated. Equatorial primates such as guenons, colobus monkeys, howlers, gibbons, chimpanzees, and gorillas might be expected to show a pattern of births uniformly distributed throughout the year, but population samples are as yet too small to make this assumption, and some equatorial monkeys, such as squirrel monkeys (genus Saimiri), are strictly seasonal breeders. Even in humans, there is evidence of high birth peaks. In Europe, the highest birth rates are reached in the first half of the year; in the United States, India, and countries in the Southern Hemisphere, in the second half. This may, however, be a cultural rather than an ecological phenomenon, for marriages in certain Western countries reach a peak in the closing weeks of the fiscal year, a fact that undoubtedly has some repercussions on the birth period.

GESTATION PERIOD AND PARTURITION

The period during which the growing fetus is protected in the uterus is characterized by a considerable range of variation among primate species, but it shows a general trend toward prolongation as one ascends the evolutionary scale. Mouse lemurs, for example, have a gestation period of 54–68 days, lemurs 132–134 days, macaques 146–186 days, gibbons 210 days, chimpanzees 230 days, gorillas 255 days, and humans (on the average) 267 days. Even small primates such as bush babies have gestations considerably longer than those of nonprimate mammals of equivalent size, a reflection of the increased complexity and differentiation of primate structure compared with that of nonprimates. Although in primates there is a general trend toward evolutionary increase in body size, there is no absolute correlation between body size and the duration of the gestation period. Marmosets, for example, are considerably smaller than spider monkeys and howler monkeys but have a slightly longer pregnancy (howler monkeys 139 days, “true” marmosets 130–150 days).

An extraordinary and somewhat inexplicable difference exists between the dimensions of the pelvic cavity and the dimensions of the head of the infant at birth in monkeys and humans on the one hand, and apes on the other. The head of the infant ape is considerably smaller than the pelvic cavity, so birth occurs easily and without prolonged labour. When the head of the infant monkey engages in the pelvis, the fit is exact, and labour may be a prolonged and difficult affair, as it is generally with humans. Human parturition, however, is generally a much more extended process than that of monkeys. Like the human infant, the monkey is born head first. Twin births are rare in most monkeys and apes, but marmosets and some lemurs and lorises habitually produce twins.

INFANCY

The degrees of maturation and mother dependency at birth are obviously closely related phenomena. Newborn primate infants are neither as helpless as kittens, puppies, or rats nor as developed as newborn gazelles, horses, and other savanna-living animals. With a few exceptions, primate young are born with their eyes open and are fully furred. Exceptions are mouse lemurs (Microcebus), gentle lemurs (Hapalemur), and ruffed lemurs (Varecia), which bear more helpless (altricial) infants and carry their young in their mouth. Primate ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The General Features of Primates

- Chapter 2: Primate Morphology

- Chapter 3: Primate Paleontology and Evolution

- Chapter 4: Lemurs

- Chapter 5: Monkeys

- Chapter 6: Apes

- Chapter 7: Early Hominins

- Chapter 8: Early Humans

- Chapter 9: Recent Humans

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Primates by Britannica Educational Publishing, John P Rafferty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.