- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reptiles and Amphibians

About this book

More than 15,000 species of reptiles and amphibians roam planet Earth today. Believed to be descendents of the dinosaurs, reptiles are scaly and cold-blooded. Amphibians lead something of a double-life, since they are capable of living in terrestrial and aquatic habitats. This colorful volume details the physical characteristics, as well as the breeding and feeding behaviors, of both reptiles and amphibians, with an up-close look at many of these remarkable creatures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reptiles and Amphibians by Britannica Educational Publishing, John P Rafferty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

REPTILES

A reptile is any member of the class Reptilia, the group of air-breathing vertebrates that have internal fertilization, amniotic development, and epidermal scales covering part or all of their body. The major groups of living reptiles—the turtles (order Testudines), tuataras (order Sphenodontida), lizards and snakes (order Squamata), and crocodiles (order Crocodylia)—account for over 8,700 species. Birds (class Aves) share a common ancestor with crocodiles in subclass Archosauria and are technically one lineage of reptiles, but they are treated separately.

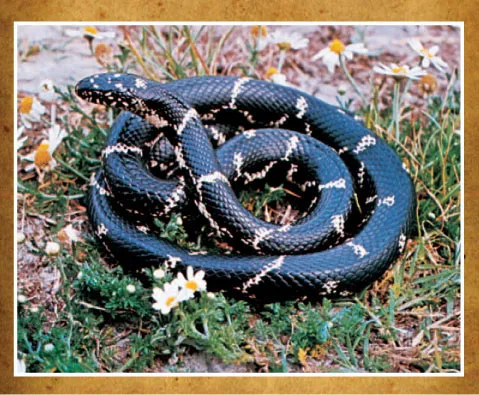

Common king snake (Lampropeltis getula). Jack Dermid

The extinct reptiles included an even more diverse group of animals that ranged from the marine plesiosaurs, pliosaurs, and ichthyosaurs to the giant plant-eating and meat-eating dinosaurs of terrestrial environments. Taxonomically, Reptilia and Synapsida (a group of mammal-like reptiles and their extinct relatives) were sister groups that diverged from a common ancestor during the Middle Pennsylvanian Epoch (approximately 312 million to 307 million years ago).

For millions of years representatives of these two groups were superficially similar. Slowly, lifestyles diverged, and from the synapsid line came hairy mammals that possessed an endothermic (warm-blooded) physiology and mammary glands for feeding their young. All birds and some groups of extinct reptiles, such as selected groups of dinosaurs, also evolved an endothermic physiology. The majority of modern reptiles possess an ectothermic (cold-blooded) physiology. Today, only the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) has a near-endothermic physiology. So far no reptile, living or extinct, has developed specialized skin glands for feeding its young.

GENERAL FEATURES OF REPTILES

Most reptiles have a continuous external covering of epidermal scales. Reptile scales contain a unique type of keratin called beta keratin. The scales and interscalar skin also contain alpha keratin, which is a trait shared with other vertebrates. Keratin is the main component of reptilian scales. Scales may be very small, as in the microscopic tubercular scales of dwarf geckos (Sphaerodactylus) or relatively large, as in the body scales of many groups of lizards and snakes. The largest scales are the scutes covering the shell of a turtle or the plates of a crocodile.

Other features also define the class Reptilia. The occipital condyle (a protuberance where the skull attaches to the first vertebra) is single. The cervical vertebrae in reptiles have midventral keels, and the intercentrum of the second cervical vertebra fuses to the axis in adults. Taxa with well-developed limbs have two or more sacral vertebrae. The lower jaw of reptiles is made up of several bones but lacks an anterior coronoid bone. In the ear a single auditory bone, the stapes, transmits sound vibrations from the eardrum (tympanum) to the inner ear. Sexual reproduction is internal, and sperm may be deposited by copulation or through the apposition of cloacae. Asexual reproduction by parthenogenesis also occurs in some groups. Development may be internal, with embryos retained in the female’s oviducts, and embryos of some species may be attached to the mother by a placenta. Development in most species is external, with embryos enclosed in shelled eggs. In all cases each embryo is encased in an amnion, a membranous fluid-filled sac.

IMPORTANCE

In the agriculture industry as a whole, reptiles do not have a great commercial value compared with fowl and hoofed mammals. Nonetheless, they have a significant economic value for food and ecological services (such as insect control) at the local level, and they are valued nationally and internationally for food, medicinal products, leather goods, and the pet trade.

Reptiles have their greatest economic impact in some temperate and many tropical areas, although this impact is often overlooked because their contribution is entirely local. A monetary value is often not assigned to any vertebrate that provides pest control. Nonetheless, many lizards control insect pests in homes and gardens; snakes are major predators of rodents, and the importance of rodent control has been demonstrated repeatedly when populations of rodent-eating snakes are decimated by snake harvesting for the leather trade. The absence of such snakes allows rodent populations to explode.

Turtles, crocodiles, snakes, and lizards are regularly harvested as food for local consumption in many tropical areas. When this harvesting becomes commercial, the demands on local reptile populations commonly exceed the ability of species to replace themselves by normal reproductive means. Harvesting is often concentrated on the larger individuals of most species, and these individuals are often the adult females and males in the population; their removal greatly reduces the breeding stock and leads to a preciptious population decline.

Regulated harvesting of large snakes and lizards is under way in parts of Indonesia. In addition, several groups of reptiles (tegu lizards in Argentina, freshwater turtles in China, and green iguanas [Iguana iguana] in Central America) are raised as livestock. Often the process of regulated harvesting begins with the removal of a few eggs, juveniles, or adults from wild populations. Stocks of reptiles are raised on farms and ranches. Farms and ranches then sell some individuals to commercial interests, while others are retained as breeding stock.

Reptiles have contributed significantly to a variety of biomedical and basic biological research programs. Snake venom studies contributed greatly to the care of heart-attack patients in the 1960s and 1970s and are widely studied in the development of pain-management drugs. Field studies of lizards and other reptiles and the manipulation of populations of various lizard species, such as the anoles (Anolis) have provided scientists opportunities to test hypotheses on different aspects of evolution. Reptile research remains an important area of evolutionary biology. Similarly, lizards and other reptiles have provided experimental models for examining physiological mechanisms, especially those associated with body heat.

SIZE RANGE

Most reptiles are measured from snout to vent, that is, the tip of the nose to the cloaca. However, measurements of total length are common for larger species, and shell length is used to gauge the size of turtles. The body size of living reptiles varies widely. Sphaerodactylus parthenopion and S. ariasae, which are the smallest dwarf geckos and also the smallest reptiles, have a snout-to-vent length of 16-18 mm (0.6-0.7 inch). In contrast, giant turtles, such as the leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), possess shell lengths of nearly 2 metres (about 7 feet). In terms of total length, the largest living reptiles are the reticulated pythons (Python reticulatus) and saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus), which may grow to more than 7 metres (23 feet) as adults. Some ancient reptile groups had members that were the largest animals ever to live on the land—some sauropod dinosaur fossils measure 20–30 metres (66–98 feet) in total length. The largest marine reptiles, the pliosaurs, grew to 15 metres (50 feet) long.

The reptile groups also show a diversity of morphologies. Some groups, such as most lizards and all crocodiles, possess strongly developed limbs, whereas other groups, such as the worm lizards and snakes, are limbless. Reptilian body flexibility ranges from the highly flexible forms found in snakes to the inflexible armoured bodies of turtles. In addition, the tails of most turtles tend to be short, especially when compared with the long heavy tails of crocodiles.

Giants in any animal group always attract attention and are often exaggerated. Anacondas (Eunectes), gigantic snakes from South America, are undoubtedly the largest living snakes. The largest species, the green anaconda (E. murinus), likely only rarely exceeds 9 metres (30 feet) in length. Nonetheless, persistent but unsubstantiated reports have been made of anacondas that are 12 metres (40 feet) long. The reticulated python (P. reticulatus) of Southeast Asia and the East Indies has been recorded at 10.1 metres (33.3 feet).

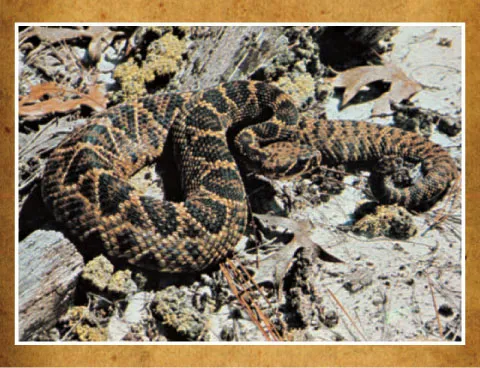

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus). Jack Dermid

At about 5.5 metres (18 feet), the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) of Asia and the East Indies is the longest venomous snake. The heaviest venomous snake is probably the eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus); its length does not exceed 2.4 metres (7.9 feet), but it may weigh as much as 15.5 kg (34 pounds). The largest of the common nonvenomous snakes is probably the keeled rat snake (Ptyas carinatus), at about 3.7 metres (12 feet).

Five species of crocodiles may grow larger than 6 metres (20 feet). Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) and estuarine (or saltwater) crocodiles (C. porosus) regularly exceed this length. The American crocodile (C. acutus), the Orinoco crocodile (C. intermedius), and the gavial (Gavialis gangeticus) may also grow larger than 6 metres; however, this is less common. The gavial normally attains a length of about 4–5 metres (12–15 feet).

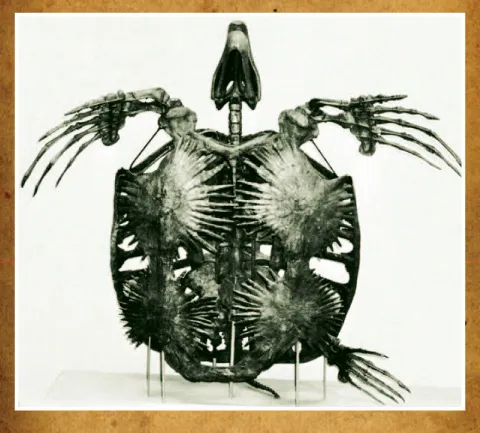

Skeleton of the Cretaceous marine turtle Archelon, length 3.25 metres (10.7 feet). Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University

The giant among living turtles is the marine leatherback sea turtle (D. coriacea), which reaches a total length of about 2.7 metres (9 feet) and a weight of about 680 kg (1,500 pounds). The largest of the land turtles is a Galapagos tortoise (Geochelone nigra), weighing about 255 kg (560 pounds).

The largest modern lizard, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) of the East Indies, is a monitor lizard that attains a total length of 3 metres (10 feet). In addition, two or three other species of monitors reach 1.8 metres (5.9 feet). The water monitor (V. salvator) may grow to a greater total length than the Komodo dragon, but it does not exceed the latter in weight. The green iguana (I. iguana), which grows to a length of about 2 metres (7 feet) comes close to that size, but no other lizard does.

Within each reptile group, with the possible exception of snakes, no living member is as large as its largest extinct representative. At about 2.7 metres (9 feet) in total length, the leatherback sea turtle is smaller than Archelon, a genus of extinct marine turtles from the Late Cretaceous (100 million to 65.5 million years ago) that was about 3.6 metres (11.8 feet) long. No modern crocodile approaches the estimated 15-metre (49-foot) length of Phobosuchus, and the Komodo dragon does not compare with Tylosaurs, a mosasaur that exceeded 6 metres (20 feet) in length. Some quadrapedal browsing dinosaurs grew to lengths of 30 metres (100 feet) and weights of 91,000 kg (200,000 pounds) or more.

The smallest reptiles are found among the geckos (family Gekkonidae), skinks (family Scincidae), and microteiids (family Gymnopthalmidae); some of these lizards grow no longer than 4 cm (about 2 inches). Certain blind snakes (family Typhlopidae) are less than 10 cm (4 inches) in total length when fully grown. Several species of turtles weigh less than 450 grams (1 pound) and reach a maximum shell length of 12.5 cm (5 inches). The smallest crocodiles are the dwarf crocodiles (Osteolaemus tetraspis), which grow to about 2 metres (7 feet), and the dwarf caimans (Paleosuchus), which typically grow to 1.7 metres (6 feet) or less.

DISTRIBUTION AND ECOLOGY

Reptiles are mainly animals of Earth’s temperate and tropical regions, and the greatest number of reptilian species live between 30° N and 30° S latitude. Nevertheless, at least two species, the European viper (Vipera berus) and the common, or viviparous, lizard (Lacerta vivipara, also called Zootoca vivipara), have populations that edge over the Arctic Circle (66° 33’39” N latitude). Other species of snakes, lizards, and turtles also live at high latitudes and altitudes and have evolved lifestyles that allow them to survive and reproduce with little more than three months of activity each year.

Reptile activity is strongly dependent on the temperature of the surrounding environment. Reptiles are ectothermic—that is, they require an external heat source to elevate their body temperature. They are also considered cold-blooded animals, although this label can be misleading, as the blood of many desert reptiles is often relatively warm. The body temperatures of many species approximate the surrounding air or the temperature of the substrate, hence a reptile can feel cold to the human touch. Many species, particularly lizards, have preferred body temperatures above 28 °C (82 °F) and only pursue their daily activities when they have elevated their body temperatures to those levels. These species maintain elevated body temperatures at a relatively constant level by shuttling in and out of sunlight.

Reptiles occur in most habitats, from the open sea to the middle elevations in mountainous habitats. The yellow-bellied sea snake (Pelamis platurus) spends all its life in marine environments. It feeds and gives birth far from any coastline and is helpless if washed ashore, whereas other sea snakes live in coastal waters of estuaries and coral reefs. Sea turtles are also predominately coastal animals, although most species have a pelagic, or open-ocean, phase that lasts from the hatchling stage to the young juvenile stage. Many snakes, crocodiles, and a few lizards are aquatic and live in freshwater habitats ranging from large rivers and lakes to small mountain streams. On land, turtles, snakes, and lizards also occur widely in forests, in grasslands, and even in true deserts. In many arid lands lizards and snakes are the major small-animal carnivores.

NORTH TEMPERATE ZONE

Reptiles of the North Temperate Zone include many ecological types. Aquatic groups are represented in both hemispheres by the water snakes, many testudinoid turtles, and the two species of Alligator. Terrestrial groups include tortoises, ground-dwelling snakes, and many genera of lizards. Arboreal snakes are few, and arboreal lizards are almost nonexistent. There are few specialized burrowing lizards in this region, but burrowing snakes are common.

The viviparous lizard (L. vivipara, or Z. vivipara) and the European viper (V. berus) are the most northerly distributed reptiles. A portion of each reptile’s geographic range occurs just north o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Reptiles

- Chapter 2: Lizards

- Chapter 3: Types of Lizards

- Chapter 4: Snakes

- Chapter 5: Types of Snakes

- Chapter 6: Turtles and Tuataras

- Chapter 7: Types of Turtles

- Chapter 8: Amphibians

- Chapter 9: Frogs and Toads

- Chapter 10: Types of Anurans

- Chapter 11: Newts, Salamanders, and Caecilians

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index