eBook - ePub

The American Revolutionary War and The War of 1812

People, Politics, and Power

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The American Revolutionary War and The War of 1812

People, Politics, and Power

About this book

Many Americans buoy their national pride and patriotism in the tableau of the American Revolution—in which every day men rose up against taxation from abroad to defeat one of the most powerful countries in the world at the time. From the midnight ride of Paul Revere to the cold winter at Valley Forge, American freedom was a right proudly won. This book investigates the important battles, speeches, and founding fathers of this important war that ended in the creation of a proud new nation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The American Revolutionary War and The War of 1812 by Britannica Educational Publishing, Jeff Wallenfeldt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

PRELUDE TO THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

Although the dates 1775 and 1783 are cemented into history as the beginning and end, respectively, of the American Revolution, the struggle for American democracy and independence began long before the “shot heard round the world” rang out in Concord, Mass., and in many ways continued well after the signing of the Peace of Paris. The founding of the United States of America came about not as the consequence of a single event but as the confluence of a variety of struggles and ideals. In some ways it was an accidental by-product of the great power conflict between France and Great Britain, but just as certainly it was a premeditated construct based on the ideals of the Enlightenment—particularly those of natural rights and the social contract. American independence was won in a bloody, grueling, and protracted contest with the world’s preeminent military power, but the battle for international respect and for the survival of the United States continued for two decades and was not finally won until Britain was confronted again in the War of 1812, characterized by many historians, appropriately, as the second American Revolution. These two wars, fought 20 years apart, were finally part of the same struggle to create a lasting democratic American republic, and they set the United States down the path toward power and prosperity.

LEGACY OF THE GREAT WAR FOR THE EMPIRE

The Great War for the Empire—or the French and Indian War, as it is known to Americans—was but another round in a century of warfare between the major European powers. First in King William’s War (1689-97), then in Queen Anne’s War (1702-13), and later in King George’s War (1744-48; the American phase of the War of the Austrian Succession), Englishmen and Frenchmen had vied for control over the Indians, for possession of the territory lying to the north of the North American colonies, for access to the trade in the Northwest, and for commercial superiority in the West Indies. In most of these encounters, France had been aided by Spain. Because of its own holdings immediately south and west of the British colonies and in the Caribbean, Spain realized that it was in its own interest to join with the French in limiting British expansion. The culmination of these struggles came in 1754 with the Great War for the Empire and in 1756 with the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, in which France and Britain’s continuing conflict was part of a more complex European war. British Prime Minister William Pitt determined that the conflict should be in every sense a national war and a war at sea. He revived the militia, reequipped and reorganized the navy, and sought to unite all parties and public opinion behind a coherent and intelligible war policy. He seized upon America and India as the main objects of British strategy. Whereas previous contests between Great Britain and France in North America had been mostly provincial affairs, with American colonists doing most of the fighting for the British, the Great War for the Empire saw sizable commitments of British troops to America. Pitt’s strategy was to allow Britain’s ally, Prussia, to carry the brunt of the fighting in Europe and thus free Britain to concentrate its troops in America.

Despite the fact that they were outnumbered 15 to 1 by the British colonial population in America, the French were nevertheless well equipped to hold their own. They had a larger military organization in America than did the English; their troops were better trained; and they were more successful than the British in forming military alliances with the Indians. The early engagements of the war went to the French and made it seem as if the war would be a short and unsuccessful one for the British. By 1758, however, with both men and material up to a satisfactory level, Britain began to implement the larger strategy that would lead to its ultimate victory: sending a combined land and sea force to gain control of the St. Lawrence River and a large land force aimed at Fort Ticonderoga to eliminate French control of Lake Champlain. The other major players in this struggle for control of North America were, of course, the American Indians. When the French and Indian War culminated in the expulsion of France from Canada, the Indians no longer could play the diplomatic card of agreeing to support whichever king—the one in London or the one in Paris—would restrain westward settlement.

Britain’s victory over France in the Great War for the Empire had been won at very great cost. British government expenditures, which had amounted to nearly £6.5 million (over $10.5 million) annually before the war, rose to about £14.5 million (over $23.5 million) annually during the war. As a result, the burden of taxation in England was probably the highest in the country’s history, much of it borne by the politically influential landed classes. Furthermore, with the acquisition of the vast domain of Canada and the prospect of holding British territories both against the various nations of Indians and against the Spaniards to the south and west, the costs of colonial defense could be expected to continue indefinitely. Parliament, moreover, had voted to give Massachusetts a generous sum in compensation for its war expenses. It therefore seemed reasonable to British opinion that some of the future burden of payment should be shifted to the colonists themselves—who until then had been lightly taxed and indeed lightly governed.

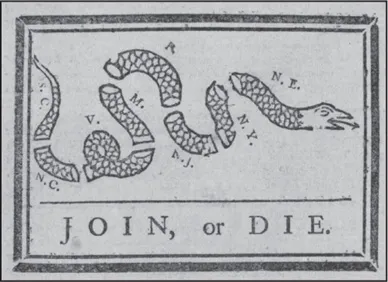

Benjamin Franklin encouraged the colonies to unite together for protection from the French in this 1754 political cartoon. Library of Congress Serial and Government Publications Division

The prolonged wars had also revealed the need to tighten the administration of the loosely run and widely scattered elements of the British Empire. If the course of the war had confirmed the necessity, the end of the war presented the opportunity. The acquisition of Canada required officials in London to take responsibility for the unsettled western territories, now freed from the threat of French occupation. The British soon moved to take charge of the whole field of Indian relations. By the royal Proclamation of 1763, a line was drawn down the Appalachians marking the limit of settlement from the British colonies, beyond which Indian trade was to be conducted strictly through British-appointed commissioners. The proclamation sprang in part from a respect for Indian rights. After Indian grievances had resulted in the start of Pontiac’s War (the rebellion led by the Ottawa chief Pontiac in 1763–64), British authorities were determined to subdue intercolonial rivalries and abuses. To this end, the proclamation organized new British territories in America—the provinces of Quebec, East and West Florida, and Grenada (in the Windward Islands)—and a vast British-administered Indian reservation west of the Appalachians, from south of Hudson Bay to north of the Floridas. It forbade settlement on Indian territory, ordered those settlers already there to withdraw, and strictly limited future settlement. For the first time in the history of European colonization in the New World, the proclamation formalized the concept of Indian land titles, prohibiting issuance of patents to any lands claimed by a tribe unless the Indian title had first been extinguished by purchase or treaty.

From London’s viewpoint, leaving a lightly garrisoned West to the fur-gathering Indians also made economic and imperial sense. The proclamation, however, caused consternation among British colonists for two reasons. It meant that limits were being set to the prospects of settlement and speculation in western lands, and it took control of the west out of colonial hands. The most ambitious men in the colonies thus saw the proclamation as a loss of power to control their own fortunes. Indeed, the British government’s huge underestimation of how deeply the halt in westward expansion would be resented by the colonists was one of the factors in sparking the 12-year crisis that led to the American Revolution. Indian efforts to preserve a terrain for themselves in the continental interior might still have had a chance with British policy makers, but they would be totally ineffective when the time came to deal with a triumphant United States of America.

THE TAX CONTROVERSY

George Grenville, who was named prime minister in 1763, was soon looking to meet the costs of defense by raising revenue in the colonies. The first measure was the Plantation Act of 1764, usually called the Revenue, or Sugar, Act, which reduced to a mere threepence the duty on molasses imported into the colonies from non-British Caribbean sources but linked with this a high duty on refined sugar and a prohibition on foreign rum. Actually a reinvigoration of the largely ineffective Molasses Act of 1733, the Sugar Act granted a virtual monopoly of the American market to British West Indies sugar planters. The 1733 act had not been firmly enforced, but this time the government set up a system of customhouses, staffed by British officers. The protected price of British sugar actually benefited New England distillers, though they did not appreciate it. More objectionable to the colonists were the stricter bonding regulations for shipmasters, whose cargoes were subject to seizure and confiscation by British customs commissioners and who were placed under the authority of the Vice Admiralty Court in distant Nova Scotia if they violated the trade rules or failed to pay duties. The court heard very few cases, but in principle it appeared to threaten the cherished British privilege of trials by local juries. Boston further objected to the tax’s revenue-raising aspect on constitutional grounds, but, despite some expressions of anxiety, the colonies in general acquiesced. Owing to this act, the earlier clandestine trade in foreign sugar, and thus much colonial maritime commerce, was severely hampered.

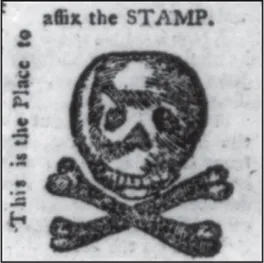

A satirical representation of an official stamp as required by the Stamp Act of 1765. Library of Congress Humanities and Social Sciences Division

Parliament next affected colonial economic prospects by passing a Currency Act (1764) to withdraw paper currencies, many of them surviving from the war period, from circulation. This was not done to restrict economic growth so much as to take out currency that was thought to be unsound, but it did severely reduce the circulating medium during the difficult postwar period and further indicated that such matters were subject to British control.

Grenville’s next move was a stamp duty, to be raised on a wide variety of transactions, including legal writs, newspaper advertisements, and ships’ bills of lading. The colonies were duly consulted and offered no alternative suggestions. The feeling in London, shared by Benjamin Franklin, was that, after making formal objections, the colonies would accept the new taxes as they had the earlier ones. But the Stamp Act (1765) hit harder and deeper than any previous parliamentary measure. As some agents had already pointed out, because of postwar economic difficulties the colonies were short of ready funds. (In Virginia this shortage was so serious that the province’s treasurer, John Robinson, who was also speaker of the assembly, manipulated and redistributed paper money that had been officially withdrawn from circulation by the Currency Act; a large proportion of the landed gentry benefited from this largesse.) The Stamp Act struck at vital points of colonial economic operations, affecting transactions in trade. It also affected many of the most articulate and influential people in the colonies (lawyers, journalists, bankers). It was, moreover, the first “internal” tax levied directly on the colonies by Parliament. Previous colonial taxes had been levied by local authorities or had been “external” import duties whose primary aim could be viewed as regulating trade for the benefit of the empire as a whole rather than raising revenue. Yet no one, either in Britain or in the colonies, fully anticipated the uproar that followed the imposition of these duties. Mobs in Boston and other towns rioted and forced appointed stamp distributors to renounce their posts; legal business was largely halted. Several colonies sent delegations to a Congress in New York in the summer of 1765, where the Stamp Act was denounced as a violation of the Englishman’s right to be taxed only through elected representatives, and plans were adopted to impose a nonimportation embargo on British goods.

A change of ministry facilitated a change of British policy on taxation. Parliamentary opinion was angered by what it perceived as colonial lawlessness, but British merchants were worried about the embargo on British imports. The marquis of Rockingham, succeeding Grenville, was persuaded to repeal the Stamp Act—for domestic reasons rather than out of any sympathy with colonial protests—and in 1766 the repeal was passed. On the same day, however, Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act, which declared that Parliament had the power to bind or legislate the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” Parliament would not have voted the repeal without this assertion of its authority.

This crisis focused attention on the unresolved question of Parliament’s relationship to a growing empire. The act particularly illustrated British insensitivity to the political maturity that had developed in the American provinces during the 18th century. The colonists, jubilant at the repeal of the Stamp Act, drank innumerable toasts, sounded peals of cannon, and were prepared to ignore the Declaratory Act as face-saving window dressing. John Adams, however, warned in his Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law that Parliament, armed with this view of its powers, would try to tax the colonies again; and this happened in 1767 when Charles Townshend became chancellor of the Exchequer in a ministry formed by Pitt, now earl of Chatham. The problem was that Britain’s financial burden had not been lifted. Townshend, claiming to take literally the colonial distinction between external and internal taxes, imposed external duties on a wide range of necessities, including lead, glass, paint, paper, and tea, the principal domestic beverage. One ominous result was that colonists now began to believe that the British were developing a long-term plan to reduce the colonies to a subservient position, which they were soon calling “slavery.” This view was ill-informed, however. Grenville’s measures had been designed as a carefully considered package; apart from some tidying-up legislation, Grenville had had no further plans for the colonies after the Stamp Act. His successors developed further measures, not as extensions of an original plan but because the Stamp Act had been repealed.

Nevertheless, the colonists were outraged. In Pennsylvania the lawyer and legislator John Dickinson wrote a series of essays that, appearing in 1767 and 1768 as Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, were widely reprinted and exerted great influence in forming a united colonial opposition. Dickinson agreed that Parliament had supreme power where the whole empire was concerned, but he denied that it had power over internal colonial affairs; he quietly implied that the basis of colonial loyalty lay in its utility among equals rather than in obedience owed to a superior.

It proved easier to unite on opinion than on action. Gradually, after much maneuvering and negotiation, a wide-ranging nonimportation policy against British goods was brought into operation. Agreement had not been easy to reach, and the tensions sometimes broke out in acrimonious charges of noncooperation. In addition, the policy had to be enforced by newly created local committees, a process that put a new disciplinary power in the hands of local men who had not had much previous experience in public affairs. There were, as a result, many signs of discontent with the ordering of domestic affairs in some of the colonies—a development that had obvious implications for the future of colonial politics if more action was needed later.

CONSTITUTIONAL DIFFERENCES WITH BRITAIN

Very few colonists wanted or even envisaged independence at this stage. (Dickinson had hinted at such a possibility with expressions of pain that were obviously sincere.) The colonial struggle for power, although charged with intense feeling, was not an attempt to change government structure but an argument over legal interpretation. The core of the colonial case was that, as British subjects, they were entitled to the same privileges as their fellow subjects in Britain. They could not constitutionally be taxed without their own consent; and, because they were unrepresented in the Parliament that voted the taxes, they had not given this consent. James Otis, in two long pamphlets, ceded all sovereign power to Parliament with this proviso. Others, however, began to question whether Parliament did have lawful power to legislate over the colonies. These doubts were expressed by the late 1760s, when James Wilson, a Scottish immigrant lawyer living in Phi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Prelude to the American Revolution

- Chapter 2: Independence

- Chapter 3: The American Revolution: An Overview

- Chapter 4: The Battles of the American Revolution

- Chapter 5: Military Figures of the American Revolution

- Chapter 6: Nonmilitary Figures of the American Revolution

- Chapter 7: The War of 1812: Major Causes

- Chapter 8: The War of 1812: An Overview

- Chapter 9: The Battles of the War of 1812

- Chapter 10: Military Figures of the War of 1812

- Chapter 11: Nonmilitary Figures of the War of 1812

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index