- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Digestive System

About this book

The satisfaction derived from savoring a steak or indulging in an ice cream sundae is only one aspect of a larger process that occurs in the human digestive system. From the moment food enters our mouths until long after we have finished a meal, the body engages in an extensive routine designed to retain nutrients and discard waste. This comprehensive book examines all the vital components involved in consuming and digesting food as well as the diseases and disorders that can plague this frequently overlooked area of the human body.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE BEGINNING OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT

The human digestive system plays a fundamental role in ensuring that all the foods and liquids we ingest are broken down into useful nutrients and chemicals. The digestive system consists primarily of the digestive tract, or the series of structures and organs through which food and liquids pass during their processing into forms that can be absorbed into the bloodstream and distributed to tissues. Other major components of the digestive system include glands that secrete juices and hormones necessary for the digestive process, as well as the terminal structures through which solid wastes pass in the process of elimination from the body.

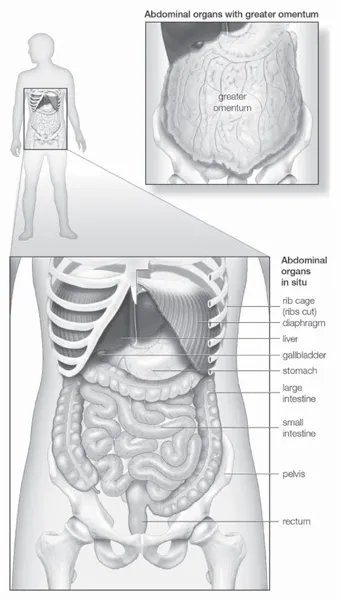

The digestive tract begins at the lips and ends at the anus. It consists of the mouth, or oral cavity, with its teeth, for grinding the food, and its tongue, which serves to knead food and mix it with saliva. Then, there is the throat, or pharynx; the esophagus; the stomach; the small intestine, consisting of the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum; and the large intestine, consisting of the cecum, a closed-end sac connecting with the ileum, the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon, and the sigmoid colon, which terminates in the rectum. Glands contributing digestive juices include the salivary glands, the gastric glands in the stomach lining, the pancreas, and the liver and its adjuncts—the gallbladder and bile ducts. All of these organs and glands contribute to the physical and chemical breaking down of ingested food and to the eventual elimination of nondigestible wastes.

The abdominal organs are supported and protected by the bones of the pelvis and ribcage and are covered by the greater omentum, a fold of peritoneum that consists mainly of fat. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

MOUTH AND ORAL STRUCTURES

Little digestion of food actually takes place in the mouth. However, through the process of mastication, or chewing, food is prepared in the mouth for transport through the upper digestive tract into the stomach and small intestine, where the principal digestive processes take place. Chewing is the first mechanical process to which food is subjected. Movements of the lower jaw in chewing are brought about by the muscles of mastication—the masseter, the temporal, the medial and lateral pterygoids, and the buccinator. The sensitivity of the periodontal membrane that surrounds and supports the teeth, rather than the power of the muscles of mastication, determines the force of the bite.

Mastication is not essential for adequate digestion. Chewing does aid digestion, however, by reducing food to small particles and mixing it with the saliva secreted by the salivary glands. The saliva lubricates and moistens dry food, while chewing distributes the saliva throughout the food mass. The movement of the tongue against the hard palate and the cheeks helps to form a rounded mass, or bolus, of food.

THE LIPS AND CHEEKS

The lips are soft, pliable anatomical structures that form the mouth margin. They are composed of a surface epidermis (skin), connective tissue, and a muscle layer. The edges of the lips are covered with reddish skin, sometimes called the vermilion border, and abundantly provided with sensitive nerve endings. The reddish skin is a transition layer between the outer, hair-bearing epidermis and the inner mucous membrane, or mucosa. The mucosa is rich in mucus-secreting glands, which together with saliva ensure adequate lubrication for the purposes of speech and mastication.

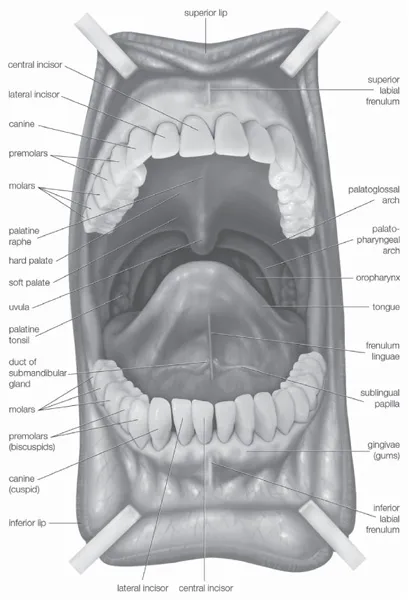

Anterior view of the oral cavity. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

In newborn infants the inner surface is much thicker, with sebaceous glands and minute projections called papillae. These structural adaptations seem to aid the process of sucking. Most of the substance of each lip is supplied by the orbicularis oris muscle, which encircles the opening. This muscle and others that radiate out into the cheeks make possible the lips’ many variations in shape and expression.

The cheeks, the sides of the mouth, are continuous with the lips and have a similar structure. A distinct fat pad is found in the subcutaneous tissue (the tissue beneath the skin) of the cheek. This pad is especially large in infants and is known as the sucking pad. On the inner surface of each cheek, opposite the second upper molar tooth, is a slight elevation that marks the opening of the parotid duct, leading from the parotid salivary gland, which is located in front of the ear. Just behind this gland are four to five mucus-secreting glands, the ducts of which open opposite the last molar tooth.

The lips are susceptible to diseases such as herpes simplex (fever blisters, or cold sores) and leukoplakia (white patches, which can be precancerous). In elderly men, ulcers on the vermilion border of the lower lip are frequently cancerous. The borders also may become cracked and inflamed from excessive drying by the weather, chemical irritants, inadequate moistening because of infection, or in reaction to antibiotics.

THE MOUTH

The mouth, which is also known as the oral (or buccal) cavity, is the orifice through which food and air enter the body. The mouth opens to the outside at the lips and empties into the throat at the rear. Its boundaries are defined by the lips, cheeks, hard and soft palates, and glottis. It is divided into two sections: the vestibule, the area between the cheeks and the teeth, and the oral cavity proper. The latter section is mostly filled by the tongue, a large muscle firmly anchored to the floor of the mouth by the frenulum linguae. In addition to its primary role in the intake and initial digestion of food, the mouth and its structures are essential in humans to the formation of speech.

The chief structures of the mouth are the teeth, which tear and grind ingested food into small pieces that are suitable for digestion; the tongue, which positions and mixes food and also carries sensory receptors for taste; and the palate, which separates the mouth from the nasal cavity, allowing separate passages for air and for food. All these structures, along with the lips, are involved in the formation of speech sounds by modifying the passage of air through the mouth.

The oral cavity and vestibule are entirely lined by mucous membranes containing numerous small glands that, along with the three pairs of salivary glands, bathe the mouth in fluid, keeping it moist and clear of food and other debris. Specialized membranes form both the gums (gingivae), which surround and support the teeth, and the surface of the tongue, on which the membrane is rougher in texture, containing many small papillae that hold the taste buds. The mouth’s moist environment and the enzymes within its secretions help to soften food, facilitating swallowing and beginning the process of digestion.

The roof of the mouth is concave and is formed by the hard and soft palate. The hard palate is formed by the horizontal portions of the two palatine bones and the palatine portions of the maxillae, or upper jaws. The hard palate is covered by a thick, somewhat pale mucous membrane that is continuous with that of the gums and is bound to the upper jaw and palate bones by firm fibrous tissue. The soft palate is continuous with the hard palate in front. Posteriorly, it is continuous with the mucous membrane covering the floor of the nasal cavity. The soft palate is composed of the palatine aponeurosis—a strong, thin, fibrous sheet—and the glossopalatine and pharyngopalatine muscles. A small projection called the uvula hangs free from the posterior of the soft palate.

The floor of the mouth can be seen only when the tongue is raised. In the midline is the frenulum linguae which—in addition to its function in anchoring the tongue to the floor of the mouth—binds each lip to the gums. On each side of this is a slight fold called a sublingual papilla, from which the ducts of the submandibular salivary glands open. Running outward and backward from each sublingual papilla is a ridge (the plica sublingualis) that marks the upper edge of the sublingual (under the tongue) salivary gland and onto which most of the ducts of that gland open.

THE GUMS

The gums, also known as the gingivae, are made up of connective tissue covered with mucous membrane. The mucous membrane is connected by thick fibrous tissue to the membrane surrounding the bones of the jaw. The gum membrane rises to form a collar around the base of the crown (exposed portion) of each tooth. Thus, the gums are attached to and surround the necks of the teeth and adjacent alveolar bone.

Healthy gums are pink, stippled, and tough and have a limited sensitivity to pain, temperature, and pressure. The gums are separated from the alveolar mucosa, which is red, by a scalloped line that approximately follows the contours of the teeth. The edges of the gums around the teeth are free and extend as small wedges into the spaces between the teeth (interdental papillae). Internally, fibres of the periodontal membrane enter the gum and hold it tightly against the teeth. Changes in colour, loss of stippling, or abnormal sensitivity are early signs of gum inflammation, or gingivitis.

Gum tissue is rich in blood vessels and receives branches from the alveolar arteries. These vessels—called alveolar because of their relationship to the alveoli dentales, or tooth sockets—also supply blood to the teeth and the spongy bone of the upper and lower jaws, in which the teeth are lodged. Before the erupting teeth enter the mouth cavity, gum pads develop; these are slight elevations of the overlying oral mucous membrane. When tooth eruption is complete, the gum embraces the neck region of each tooth.

THE TEETH

The teeth are hard, white structures found in the mouth. Usually used for mastication, the teeth of different vertebrate species are sometimes specialized. The teeth of snakes, for example, are very thin and sharp and usually curve backward. They function in capturing prey but not in chewing, because snakes swallow their food whole. The teeth of carnivorous mammals, such as cats and dogs, are more pointed than those of primates, including humans. The canines are long, and the premolars lack flat grinding surfaces, being more adapted to cutting and shearing (often the more posterior molars are lost). On the other hand, herbivores such as cows and horses have very large, flat premolars and molars with complex ridges and cusps; the canines are often totally absent.

The differences in the shapes of teeth are functional adaptations. Few animals can digest cellulose, yet the plant cells used as food by herbivores are enclosed in cellulose cell walls that must be broken down before the cell contents can be exposed to the action of digestive enzymes. By contrast, the animal cells in meat are not encased in nondigestible matter and can be acted upon directly by digestive enzymes. Consequently, chewing is not so essential for carnivores as it is for herbivores. Humans, who are omnivores (eaters of plants and animal tissue), have teeth that belong, functionally and structurally, somewhere between the extremes of specialization attained by the teeth of carnivores and herbivores.

Each tooth consists of a crown and one or more roots. The crown is the functional part of the tooth that is visible above the gum. The root is the unseen portion that supports and fastens the tooth in the jawbone. The shapes of the crowns and the roots vary in different parts of the mouth and from one animal to another. The teeth on one side of the jaw are essentially a mirror image of those located on the opposite side. The upper teeth differ from the lower and are complementary to them.

TOOTH STRUCTURE

All true teeth have the same general structure and consist of three layers. In mammals an outer layer of enamel—which is wholly inorganic and is the hardest tissue in the body—covers part or all of the crown of the tooth. The middle layer of the tooth is composed of dentine, which is less hard than enamel and similar in composition to bone. The dentine forms the main bulk, or core, of each tooth and extends almost the entire length of the tooth, being covered by enamel on the crown portion and by cementum on the roots. Dentine is nourished by the pulp, which is the innermost portion of the tooth.

The pulp consists of cells, tiny blood vessels, and a nerve and occupies a cavity located in the centre of the tooth. The pulp canal is long and narrow with an enlargement, called the pulp chamber, in the coronal end. The pulp canal extends almost the whole length of the tooth and communicates with the body’s general nutritional and nervous systems through the apical foramina (holes) at the end of the roots. Below the gumline extends the root of the tooth, which is covered at least partially by cementum. The latter is similar in structure to bone but is less hard than dentine. Cementum affords a thin covering to the root and serves as a medium for attachment of the fibres that hold the tooth to the surrounding tissue (periodontal membrane). Gum is attached to the adjacent alveolar bone and to the cementum of each tooth by fibre bundles.

TOOTH FORM AND FUNCTION

Like most other mammals, humans have two successive sets of teeth during life. The first set of teeth are called primary, or deciduous, ones, and the second set are called permanent ones. Humans have 20 primary and 32 permanent teeth.

Primary teeth differ from permanent teeth in being smaller, having more pointed cusps, being whiter and more prone to wear, and having relatively large pulp chambers and small, delicate roots. The primary teeth begin to appear about six months after birth, and the primary dentition is complete by age 2½. Shedding begins about age 5 or 6 and is finished by age 13. The primary teeth are shed when their roots are resorbed as the permanent teeth push toward the mouth cavity in the course of their growth.

In humans the primary dentition consists of 20 teeth—four incisors, two canines, and four molars in each jaw. The primary molars are replaced in the adult dentition by the premolars, or bicuspid teeth. The 12 adult molars of the permanent dentition erupt (emerge from the gums) behind the primary teeth and do not replace any of these, giving a total of 32 teeth in the permanent dentition. The permanent dentition is thus made up of four incisors, two canines, four premolars, and six molars in each jaw.

Incisor teeth are the teeth at the front of the mouth, and they are adapted for plucking, cutting, tearing, and holding. The biting portion of an incisor is wide and thin, making a chisel-shaped cutting edge. The upper incisors have a delicate tactile sense that enables them to be used for identifying objects in the mouth by nibbling. Next to the incisor on each side is a canine, or cuspid tooth. It frequently is pointed and rather peglike in shape and, like the incisors, has the function of cutting and tearing food.

Premolars and molars have a series of elevations, or cusps, that are used for breaking up particles of food. Behind each canine are two premolars, which can both cut and grind food. Each premolar has two cusps (hence the name bicuspid). The molars, by contrast, are used exclusively for crushing and grinding. They are the teeth farthest back in the mouth. Each molar typically has four or five cusps. The third molar in humans tends to be variable in size, number of roots, cusp pattern, and eruption. The number of roots f...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Beginning of the Digestive Tract

- Chapter 2: The Passage of Food to the Stomach

- Chapter 3: Anatomy of the Lower Digestive Tract

- Chapter 4: Digestive Glands and Hormones

- Chapter 5: Features of the Digestive Tract

- Chapter 6: Diseases of the Upper Digestive Tract

- Chapter 7: Diseases of the Intestines

- Chapter 8: Diseases of the Liver and Pancreas

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Digestive System by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kara Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Physiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.