eBook - ePub

The Geography of India

Sacred and Historic Places

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

With a landscape as diverse as the multitude of people that inhabit it, India hosts a wide range of communities, from remote villages nestled in the Himalayas to thriving urban centers. In many ways, it is a land of contrasts, as reflected in its geography—shaped as much by the annual monsoon season as the arid deserts that punctuate the nation. In this volume, readers will experience a juxtaposed journey, visiting both areas that have remained untouched for centuries and areas of technological advancement that have brought the country to the forefront of innovation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Geography of India by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kenneth Pletcher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

GEOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW

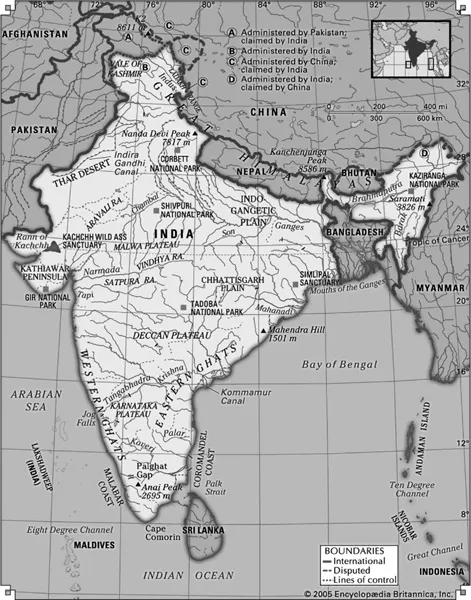

India—officially Republic of India (Hindi: Bharat)—is a country that occupies the greater part of South Asia. It is a constitutional republic consisting of 28 states, each with a substantial degree of control over its own affairs; six less fully empowered union territories; and the Delhi national capital territory, which includes New Delhi, India’s capital. With roughly one-sixth of the world’s total population, India is the second most populous country, after China, and, in area, it ranks as the seventh-largest country in the world. India’s frontier, which is roughly one-third coastline, abuts six countries. It is bounded to the northwest by Pakistan, to the north by Nepal, China, and Bhutan; and to the east by Myanmar (Burma). Bangladesh to the east is surrounded by India to the north, east, and west. The island country of Sri Lanka is situated some 40 miles (65 km) off the southeast coast of India across the Palk Strait and Gulf of Mannar.

The land of India—together with Bangladesh and most of Pakistan—forms a well-defined subcontinent, set off from the rest of Asia by the imposing northern mountain rampart of the Himalayas and by adjoining mountain ranges to the west and east. The most northerly portion of the subcontinent, the Kashmir region, has been in dispute between India and Pakistan since British India was partitioned into the two countries in 1947. Although each country claims sovereignty over Kashmir, for decades the region has been divided administratively between the two; in addition, China administers portions of Kashmir territory adjoining its border.

Much of India’s territory lies within a large peninsula, surrounded by the Arabian Sea to the west and the Bay of Bengal to the east; Cape Comorin, the southernmost point of the Indian mainland, marks the dividing line between these two bodies of water. Two of India’s union territories are composed entirely of islands: Lakshadweep, in the Arabian Sea, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which lie between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.

RELIEF

It is now generally accepted that India’s geographic position, continental outline, and basic geologic structure resulted from a process of plate tectonics—the shifting of enormous, rigid crustal plates over the Earth’s underlying layer of molten material. India’s landmass, which forms the northwestern portion of the Indian-Australian Plate, began to drift slowly northward toward the much larger Eurasian Plate several hundred million years ago (after the former broke away from the ancient southern-hemispheric supercontinent known as Gondwana, or Gondwanaland). When the two finally collided (approximately 50 million years ago), the northern edge of the Indian-Australian Plate was thrust under the Eurasian Plate at a low angle. The collision reduced the speed of the oncoming plate, but the underthrusting, or subduction, of the plate has continued into contemporary times.

The effects of the collision and continued subduction are numerous and extremely complicated. An important consequence, however, was the slicing off of crustal rock from the top of the under-thrusting plate. These slices were thrown back onto the northern edge of the Indian landmass and came to form much of the Himalayan mountain system. The new mountains—together with vast amounts of sediment eroded from them—were so heavy that the Indian-Australian Plate just south of the range was forced downward, creating a zone of crustal subsidence. Continued rapid erosion of the Himalayas added to the sediment accumulation, which was subsequently carried by mountain streams to fill the subsidence zone and cause it to sink more.

India’s present-day relief features have been superimposed on three basic structural units: the Himalayas in the north, the Deccan (plateau region) in the south, and the Indo-Gangetic Plain (lying over the subsidence zone) between the two.

THE HIMALAYAS

The Himalayas (from the Sanskrit words hima, “snow,” and alaya, “abode”), the loftiest mountain system in the world, form the northern limit of India. This great, geologically young mountain arc is about 1,550 miles (2,500 km) long, stretching from the peak of Nanga Parbat (26,660 feet [8,126 metres]) in Pakistan-administered Kashmir to the Namcha Barwa peak in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Between these extremes the mountains fall across India, southern Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan. The width of the system varies between 125 and 250 miles (200 and 400 km).

Within India the Himalayas are divided into three longitudinal belts, called the Outer, Lesser, and Great Himalayas. At each extremity there is a great bend in the system’s alignment, from which a number of lower mountain ranges and hills spread out. Those in the west lie wholly within Pakistan and Afghanistan, while those to the east straddle India’s border with Myanmar (Burma). North of the Himalayas are the Plateau of Tibet and various Trans-Himalayan ranges, only a small part of which, in the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir state, are within the territorial limits of India.

Because of the continued subduction of the Indian peninsula against the Eurasian Plate, the Himalayas and the associated eastern ranges remain tectonically active. As a result, the mountains are still rising, and earthquakes—often accompanied by landslides—are common. Several since 1900 have been devastating, including one in 1934 in what is now Bihar state that killed more than 10,000 persons. In 2001 another tremor, farther from the mountains, in Gujarat state, was less powerful but caused extensive damage, taking the lives of more than 20,000 people and leaving more than 500,000 homeless. The relatively high frequency and wide distribution of earthquakes likewise have generated controversies about the safety and advisability of several hydroelectric and irrigation projects.

THE OUTER HIMALAYAS (THE SHIWALIK RANGE)

The southernmost of the three mountain belts are the Outer Himalayas, also called the Shiwalik Range. Crests in the Shiwaliks, averaging from 3,000 to 5,000 feet (900 to 1,500 metres) in elevation, seldom exceed 6,500 feet (2,000 metres). The range narrows as it moves east and is hardly discernible beyond the Duars, a plains region in West Bengal state. Interspersed in the Shiwaliks are heavily cultivated flat valleys (duns) with a high population density. To the south of the range is the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Weakly indurated, largely deforested, and subject to heavy rain and intense erosion, the Shiwaliks provide much of the sediment transported onto the plain.

THE LESSER HIMALAYAS

To the north of the Shiwaliks and separated from them by a fault zone, the Lesser Himalayas (also called the Lower or Middle Himalayas) rise to heights ranging from 11,900 to 15,100 feet (3,600 to 4,600 metres). Their ancient name is Himachal (Sanskrit: hima, “snow,” and acal, “mountain”). These mountains are composed of both ancient crystalline and geologically young rocks, sometimes in a reversed stratigraphic sequence because of thrust faulting. The Lesser Himalayas are traversed by numerous deep gorges formed by swift-flowing streams (some of them older than the mountains themselves), which are fed by glaciers and snowfields to the north.

THE GREAT HIMALAYAS

The northernmost Great, or Higher, Himalayas (in ancient times, the Himadri), with crests generally above 16,000 feet (4,900 metres) in elevation, are composed of ancient crystalline rocks and old marine sedimentary formations. Between the Great and Lesser Himalayas are several fertile longitudinal vales; in India the largest is the Vale of Kashmir, an ancient lake basin with an area of about 1,700 square miles (4,400 square km). The Great Himalayas, ranging from 30 to 45 miles (50 to 75 km) wide, include some of the world’s highest peaks. The highest, Mount Everest (at 29,035 feet [8,850 metres]), is on the China-Nepal border, but India also has many lofty peaks, such as Kanchenjunga (28,169 feet [8,586 metres]) on the border of Nepal and the state of Sikkim and Nanda Devi (25,646 feet [7,817 metres]), Kamet (25,446 feet [7,755 metres]), and Trisul (23,359 feet [7,120]) in Uttaranchal. The Great Himalayas lie mostly above the line of perpetual snow and thus contain most of the Himalayan glaciers.

ASSOCIATED RANGES AND HILLS

In general, the various regional ranges and hills run parallel to the Himalayas’ main axis. These are especially prominent in the northwest, where the Zaskar Range and the Ladakh and Karakoram ranges, all in Jammu and Kashmir state, run to the northeast of the Great Himalayas. Also in Jammu and Kashmir is the Pir Panjal Range, which, extending along the southwest of the Great Himalayas, forms the western and southern flanks of the Vale of Kashmir.

Barren mountains of Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir state, India. Courtesy of Iffat Fatima

At its eastern extremity, the Himalayas give way to a number of smaller ranges running northeast-southwest—including the heavily forested Patkai Range and the Naga and Mizo hills—which extend along India’s borders with Myanmar and the southeastern panhandle of Bangladesh. Within the Naga Hills, the reedy Logtak Lake, in the Manipur River valley, is an important feature. Branching off from these hills to the northwest are the Mikir Hills, and to the west are the Jaintia, Khasi, and Garo hills, which run just north of India’s border with Bangladesh. Collectively, the latter group is also designated as the Shillong (Meghalaya) Plateau.

THE INDO-GANGETIC PLAIN

The second great structural component of India, the Indo-Gangetic Plain (also called the North Indian Plain), lies between the Himalayas and the Deccan. The plain occupies the Himalayan fore-deep, formerly a seabed but now filled with river-borne alluvium to depths of up to 6,000 feet (1,800 metres). The plain stretches from the Pakistani provinces of Sind and Punjab in the west, where it is watered by the Indus River and its tributaries, eastward to the Brahmaputra River valley in Assam state.

The Ganges (Ganga) River basin (mainly in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar states) forms the central and principal part of this plain. The eastern portion is made up of the combined delta of the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, which, though mainly in Bangladesh, also occupies a part of the adjacent Indian state of West Bengal. This deltaic area is characterized by annual flooding attributed to intense monsoon rainfall, an exceedingly gentle gradient, and an enormous discharge that the alluvium-choked rivers cannot contain within their channels. The Indus River basin, extending west from Delhi, forms the western part of the plain; the Indian portion is mainly in the states of Haryana and Punjab.

The overall gradient of the plain is virtually imperceptible, averaging only about 6 inches per mile (95 mm per km) in the Ganges basin and slightly more along the Indus and Brahmaputra. Even so, to those who till its soils, there is an important distinction between bhangar—the slightly elevated, terraced land of older alluvium—and khadar, the more fertile fresh alluvium on the low-lying floodplain. In general, the ratio of bhangar areas to those of khadar increases upstream along all major rivers. An exception to the largely monotonous relief is encountered in the southwestern portion of the plain, where there are gullied badlands centring on the Chambal River. That area has long been famous for harbouring violent gangs of criminals called dacoits, who find shelter in its many hidden ravines.

The Great Indian, or Thar, Desert, forms an important southern extension of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It is mostly in India but also extends into Pakistan and is mainly an area of gently undulating terrain, and within it are several areas dominated by shifting sand dunes and numerous isolated hills. The latter provide visible evidence of the fact that the thin surface deposits of the region, partially alluvial and partially wind-borne, are underlain by the much older Indian-Australian Plate, of which the hills are structurally a part.

THE DECCAN

The remainder of India is designated, not altogether accurately, as either the Deccan plateau or peninsular India. It is actually a topographically variegated region that extends well beyond the peninsula—that portion of the country lying between the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal—and includes a substantial area to the north of the Vindhya Range, which has popularly been regarded as the divide between Hindustan (northern India) and the Deccan (from Sanskrit dakshina, “south”).

Having once constituted a segment of the ancient continent of Gondwana, this land is the oldest and most stable in India. The plateau is mainly between 1,000 and 2,500 feet (300 to 750 metres) above sea level, and its general slope descends toward the east. A number of the hill ranges of the Deccan have been eroded and rejuvenated several times, and only their remaining summits testify to their geologic past. The main peninsular block is composed of gneiss, granite-gneiss, schists, and granites, as well as of more geologically recent basaltic lava flows.

THE WESTERN GHATS

The Western Ghats, also called the Sahyadri, are a north-south chain of mountains or hills that mark the western edge of the Deccan plateau region. They rise abruptly from the coastal plain as an escarpment of variable height, but their eastern slopes are much more gentle. The Western Ghats contain a series of residual plateaus and peaks separated by saddles and passes. The hill station (resort) of Mahabaleshwar, located on a laterite plateau, is one of the highest elevations in the northern half, rising to 4,700 feet (1,430 metres). The chain attains greater heights in the south, where the mountains terminate in several uplifted blocks bordered by steep slopes on all sides. These include the Nilgiri Hills, with their highest peak, Doda Betta (8,652 feet [2,637 metres]); and the Anaimalai, Palni, and Cardamom hills, all three of which radiate from the highest peak in the Western Ghats, Anai Peak (Anai Mudi, 8,842 feet [2,695 metres]). The Western Ghats receive heavy rainfall, and several major rivers—most notably the Krishna (Kistna) and the two holy rivers, the Godavari and the Kaveri (Cauvery)—have their headwaters there.

THE EASTERN GHATS

The Eastern Ghats are a series of discontinuous low ranges running generally northeast-southwest parallel to the coast of the Bay of Bengal. The largest single sector—the remnant of an ancient mountain range that eroded and subsequently rejuvenated—is found in the Dandakaranya region between the Mahanadi and Godavari rivers. This narrow range has a central ridge, the highest peak of which is Arma Konda (5,512 feet [1,680 metres]) in Andhra Pradesh state. The hills become subdued farther southwest, where they are traversed by the Godavari River through a gorge 40 miles (65 km) long. Still farther southwest, beyond the Krishna River, the Eastern Ghats appear as a series of low ranges and hills, including the Erramala, Nallamala, Velikonda, and Palkonda. Southwest of the city of Chennai (Madras), the Eastern Ghats continue as the Javadi and Shevaroy hills, beyond which they merge with the Western Ghats.

INLAND REGIONS

The northernmost portion of the Deccan may be termed the peninsular foreland. This large, ill-defined area lies between the peninsula proper to the south (roughly d...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Geographic Overview

- Chapter 2: Human Interactions with India’s Environment

- Chapter 3: Major Physical Features of the Subcontinent

- Chapter 4: Spotlight on India’s World Heritage Sites and Other Notable Locations

- Chapter 5: The Major Cities of Northern and Northwestern India

- Chapter 6: The Major Cities of Northeastern India

- Chapter 7: The Major Cities of Central India

- Chapter 8: The Major Cities of Southern India

- Chapter 9: Selected Northern and Northwestern Indian States

- Chapter 10: Selected Northeastern Indian States

- Chapter 11: Selected Central Indian States

- Chapter 12: Selected Southern Indian States

- Chapter 13: India’s Union Territories

- Chapter 14: The Kashmir Region

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Statistical Summary

- Glossary

- For Further Reading

- Index