- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Victorian Childhood

About this book

First published in 1932. This title is a first-person account of growing up in Victorian England. The book examines many aspects of the British Empire, and the family life and education of the poet, writer and high society hostess Claire Annabel Caroline Grant Duff. A Victorian Childhood will be of interest to students of history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Victorian Childhood by Annabel Huth Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A VICTORIAN CHILDHOOD

CHAPTER I

ALL people who possess a memory should write their recollections when they reach the age of sixty. Even if their lives have been apparently uninteresting, they are of importance to their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. A dull grandfather is better than no grandfather at all, and this holds good in the present century more than it did at any time before. Formerly tradition was an accepted thing; every boy and girl listened to the stories their forbears told them, and amassed most of what is known of wisdom and history in this way. There was no such thing as a generation which knew nothing of what the generation before it had thought, and felt, and learnt; and the store-house of the world’s wisdom was kept supplied. Now a spirit has arisen which we can only call, because of the nation which has most carried it into force, Bolshevist. That spirit dislikes tradition and says that our only chance of happiness is to scrap everything that the world has learnt and begin afresh. Many people believe that this is impossible, but it is terribly true that it can be done. Nothing is so easy as to wipe out the preceding generation. There must have been an immense number of cultures in the past that have left nothing behind them, to the world’s permanent loss.

This is my excuse for writing down many things which will interest nobody except my own children. If every one wrote their memoirs most would eventually be burnt, but many details would be preserved for which future generations would be grateful. For I do not believe that the present Bolshevistic point of view raging in England and on the Continent will endure; there is bound to be a reaction, and then all that can be collected to tell of the past will come into its own again.

The first thing I remember distinctly is sitting on the lawn in front of the house we lived in then, Hampden House, the seat of the Earl of Buckinghamshire. I must have been about three and a half and it was hot weather. I was so small that the daisies came up round my fat legs. There was a constant discussion between my parents on the subject of daisies—my mother preferred the lawns shorn like velvet but my father loved the daisies. On this occasion my mother was sitting near me on the grass, and I remember thinking how beautiful she was and how beautiful the sun was. I remember running into the laurels afterwards and biting one of the leaves and I can still recall the queer taste of prussic acid.

At the back of the house were cedars and all that summer I heard the call of the peacocks as they went to bed in the branches. I also remember a dreadful altercation with my nurse. We had an argument, I saying that toads did sit on toadstools, and she that they did not. I surreptitiously caught a toad and put it on a toadstool under the cedars, where it remained, too frightened to move, and then I took her to see it. She smacked me thoroughly, having seen through the ruse. There was a tame toad at Hampden, who lived in the hollow of an old apple-tree, where we used to go and see him, and my brothers gave him slugs every morning. There was a very old gardener with a long beard called Lily. He grew mushrooms under a copy of the Ten Commandments, which had been removed from the village church on some occasion. He produced wonderful mushrooms and years afterwards I heard my mother say that he thought it was something to do with the virtue of the Ten Commandments. There was a fountain and I remember one of my brothers trying to sail on it in a tub and falling in. My mother had it filled up after that with earth and Arthur Hughes did a charming old-fashioned picture of her sitting by the fountain with a peacock and my brother Adrian.

Hampden was very haunted and though the servants were strictly forbidden to speak to the children about such things, we knew that there was something odd about it. One day Adrian took me down the passage and we peeped into the haunted room. Sir Louis Mallet, the father of the present Sir Louis, was badly frightened in that room by a sense of terror and by hearing a woman in a silk dress swish past his bed. He was so scared that he left his dressing-room and spent the night in another room. When I was older I have often heard my mother relate her experiences there. She was, I think, a medium, for she had a very curious psychic sense. Her boudoir lay right at the end of a long series of sitting-rooms, next a staircase which led to the haunted room. Every night at ten o’clock she would hear a girl’s light footsteps run along the passage and down the staircase. If the door was unlocked, it would burst open, if locked some one would fumble with the handle. My father was in London for the session and she was an extraordinarily brave woman. She bore it for three months and then changed her sitting-room.

LADY GRANT DUFF WITH HER SON ADRIAN

On another occasion her Blenheim spaniel ran down the passage to the great hall very late one winter night. She called, but as he did not come back, she followed him. To her astonishment the whole place, which was generally lit from a big sconce of candles in the middle of the hall, was brilliantly lighted. Her first thought was, ‘The servants have left the lights on and we shall be burned in our beds.’

Then looking up she saw the sconce was unlighted, and the dog came shivering and crouched near her skirt as if it were scared. She admitted that she had not the courage to go on down the passage to the hall but went back and locked her door.

As a girl she was a friend of the branch of the Hobart Hampden family who did not then hold the title. She often stayed with Lady Hobart and Mrs. Bacon, then Miss Carrs. George Cameron Hampden, the heir to the title, lived abroad, and was a distant cousin, so my mother’s friends had no thought of inheriting. One night when staying with them she had a very strange dream. She dreamt that she married and went to live at Hampden House, which she did not know then, but had often. heard talked about. Whilst she was there a son was born to her, and shortly after, the property returned to her branch of the Hobart Hampdens, through a box which stood in the front hall. She went down to breakfast full of her dream and they all chaffed her very much. ‘But what was the box like?’ asked Lady Hobart. ‘Were there papers in it?’—‘I do not know,’ said my mother, ‘I know it was very heavy, it had to be put on trestles.’ … ‘But what was the shape?’—‘I cannot remember,’ said my mother, ‘I only know that the property came back to your branch through a box which stood in the front hall.’

Years after she married, Hampden House came into the market and my father took it for five years. Whilst he was there a brother was born. Cameron Hampden died abroad, his body was brought back and laid in the front hall on trestles and the other branch of the family came in for the title. I have heard both Lady Hobart and my mother tell this story and they agreed in every particular. It seems to me that I vaguely remember the hall at Hampden, hung with black, and being very frightened. But I expect that this was told me later.

I cannot have been more than four and a half when my nurse Mrs. Cave, of whom I was very fond, fell ill and went to the seaside, and I was left in the charge of Nurse Maunder, who was a Baptist and a typical Calvinist, cruel, rigid, but with the virtues of her defects, clean, absolutely honest, hard working, and conscientious. I had been very grubby and was taken to my mother for punishment, and she thrashed me with a small rhinoceros-hide whip with a gold top, which she used when riding. I do not suppose she hurt me very much, though I thought she did. But far worse were the agonies of shame I suffered, both at the time and for weeks afterwards. I scarcely dared walk round the garden because I felt all the gardeners knew, and when Mrs. Cave came back and I told her about the episode, I sobbed and sobbed till she cried too. Shortly after, she went away and I heard later that she was supposed not to be quite normal. But I adored her and I was broken-hearted. Nurse Maunder reigned in her stead.

At three and a half I was put on a pony, Peri, a Shetland, and went for delightful rides with a groom called Harry, and a dog called Spot. I still have a little old photograph of myself at this period in the long dangerous riding-habit that was considered essential. When Peri and Pixie first came to Eden, my father’s house in Scotland, from the Shetland Isles, they would not touch hay, and seaweed had to be procured for them. They gradually learnt to eat hay.

I remember on my fourth birthday being made to read to my grandfather, Edward Webster, out of a book called My Mother which contained a story called ‘The Dog’s Dinner Party’ and one called ‘The Peacock’s At Home’ and the aforesaid ‘My Mother’, a poem no one remembers now except for the delightful parody about Gladstone and Huxley in which occurs the much-quoted verse:

ANNABEL JACKSON AT FOUR YEARS OLD

‘Who filled his soul with carnal pride?

Who made him say that Moses lied

About the little hare’s inside?

The Devil.’

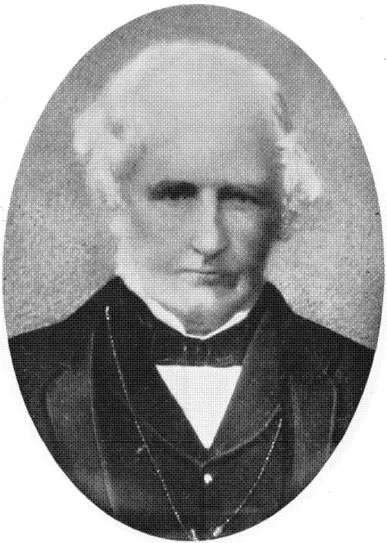

It must have been a few months after this that I was taken down to Ealing to see my grandfather Webster when he was dying and I remember being lifted up to kiss him. He was beautiful even as an old man. He and his brother were so handsome that old men in Derbyshire used to say that when the Websters walked into church people would stand up to look at them. He lived in a little house called North Lodge, on Ealing Green, with my grandmother who was a Miss Ainsworth, of Smithills Hall, Bolton-le-Moors, a house that later played such a big part in my life.

A few months after his death Adrian and I and the baby Hampden were sent to Ealing whilst my mother went to Rome. We liked being there, but I remember my winter was poisoned by a dreadful horror of bears. I used to dream about bears and I was always thinking that there were bears either under or sitting on my bed. The part that dreams play in the life of an imaginative child is now known to be very important. But then, whenever one spoke of dreams one was told not to be a silly girl and never to bore people by recounting one’s visions. I always made my own children tell me all their dreams and they were enormously helpful in teaching me about their characters and how to train them. I know many mothers who did the same thing through sheer intuition long before Freud and Jung told the world how vital these observations were. The study is an old one; these men are only working on the same lines as Joseph and Daniel in the Old Testament.

It was during that winter that I began to dream consistently and usually very frightening dreams. As I said, many were about bears, but one which was to me more alarming than any centred on the word ‘magic’, which I had picked up somewhere. It would be a little coil of rope that would terrify me sometimes, or some other quite unimportant thing, but always somebody would say, ‘Ah, yes, that is magic’—and I would be scared. I cannot remember whether it was that year or the next that I began to have a dream which left me quite exhausted in the morning. I thought that I was sitting in a boat being rowed down a river. The man who was rowing me had a cowl over his face like a monk and I could only see his eyes, which were intensely bright. He never said a word, but he rowed and rowed, and as he rowed the river got narrower and narrower until at last it came between two cliffs and it wound on and became like a ditch and the cliffs came together, and I woke screaming, or sometimes to find myself head downwards in the bed with the clothes right over me. The last time I had this dream I must have been about seven years old and when we reached the narrow part the man stood up and said, ‘Now you will see me no more until you see faces upon the trees.’ Imagine my terror when, a week later, my brother Adrian said, ‘Isn’t that like a face on the chestnut-tree?’ But I have never had that dream again.

It was when I was eight or nine that I began to have lovely dreams. I suppose I got stronger and less nervous by that time and more able to cope with outside things. A small child is so helpless and overwhelmed. Perhaps the greatest moment in its life is when the child suddenly realizes that it can stand up against the objects animate and inanimate which till then have been too much for it.

At Ealing I remember picking flowered grasses and Herb Robert, and the excitement of finding something green at last after the long winter. There was a monkey-puzzle tree in the garden and we admired this immensely, though it was like all monkey-puzzles, a hideous thing. Few people had them then and we thought it a great asset.

My grandmother had a couple of fields and an old horse which used to take her about in a brougham. She had an old butler called Peprel, an old maid called Vine and an old cook. It was very peaceful there and whenever I went I wished that I was an only child. I was sometimes allowed to play very quietly in the drawing-room where my grandmother sat by the fire in an arm-chair, wearing a frilled tulle cap and black dress with a white collar and cuffs of tulle. I never took any toys to the drawing-room, but my grandmother let me play with a little silver stork seal and a small bronze figure of the Venus of Milo and a bronze inkstand made to represent the temple of Vesta. My grandmother had an old friend called Mrs. Minty who lived next door, and two old Miss Percivals came in from their house opposite. I believe they were the sisters of the Spencer Percival who was assassinated. The ground and all around it is now covered with horrid little villas, but then it was almost country and very charming.

EDWARD WEBSTER

I read Evenings at Home in that drawing-room and Bewick’s Birds and Miss Mitford’s Our Village and the History of the Robins.

My mother’s father’s family were a wild lot. I think it was her great-great-grandfather who played away first his money, then his wife’s jewellery, and finally his estate in a single night, and walked out of his home next morning penniless.

One of her forebears was a niece of Dr. Taylor, the friend of Dr. Johnson. She was very foolish and ran away with a handsome gypsy, and her family quite naturally never saw her again. She went to another county and lived in great poverty, and of course had a large family. But old Dr. Taylor, hearing that one of her sons was a decent human being, sent for the lad and made him a footman in his establishment. When Dr. Taylor’s will was to be read and all the relations were assembled for the purpose, William came into the room carrying coals to make up the fire. ‘Go upstairs and take off your livery, William,’ said the old family lawyer, ‘for you will never wear it again.’ Dr. Taylor had left him everything. He went up to Oxford, where he made charming friends and did very well. He eventually married and became my great-grandfather.

From Ealing we went to 4 Queen’s Gate Gardens, which at that time belonged to my father. It was so country then that he used to say to the cabman when he came out of the House of Commons at night, ‘Drive along the Cromwell Road till you come to a hedge and then turn right.’

It was this spring that Adrian and I had measles in London and were nursed by an Irish nurse who danced jigs...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- List Of Illustrations

- Frontispiece

- Dedication

- Contents

- Chapter I

- Chapter II

- Chapter III

- Chapter IV

- Chapter V

- Chapter VI

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- Index