- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics

About this book

The Routledge Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics provides accessible and concise explanations of key concepts and terms related to research methods in applied linguistics. Encompassing the three research paradigms of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods, this volume is an essential reference for any student or researcher working in this area.

This volume provides:

- A–Z coverage of 570 key methodological terms from all areas of applied linguistics;

- detailed analysis of each entry that includes an explanation of the head word, visual illustrations, cross-references to other terms, and further references for readers;

- an index of core concepts for quick reference.

Comprehensively covering research method terminology used across all strands of applied linguistics, this encyclopedia is a must-have reference for the applied linguistics community.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Routledge Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics by A. Mehdi Riazi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A

A-B-A designs

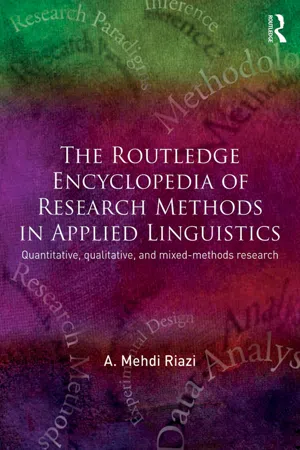

A-B-A designs refer to those research designs in which a single case is measured repeatedly at three points in time. The first and the third measurement points are called the baseline, and the second measurement point is referred to as the treatment point because the case receives some treatment at this point. The case is measured repeatedly at baseline point (A) on an outcome measure, receives a treatment at time point (B) while being measured repeatedly on the same outcome measure, and is again measured repeatedly when the treatment is lifted at a second baseline point (A) on the same outcome measure. A-B-A designs are a combination of time-series and experimental designs. Figure A.1 presents an A-B-A design.

A-B-A designs are similar to time-series designs because the case is measured repeatedly over time so that different measurements can be compared for any short-term and long-term changes in the outcome measure and due to the effect of the treatment provided to the case. These designs are also similar to experimental designs because the case receives some treatment and the outcome measure is compared before and after treatment and with baseline measurements. The treatment period is usually continued for the same length of time as the original baseline or until some stable changes occur in the outcome measure. After the treatment period, the case will be measured again in the same way as it was done in the first baseline (A) and while the treatment is withdrawn. The assumption is that the outcome measures of the second baseline must revert to the original baseline measures to rule out rival explanations. Another version of A-B-A design is A-B-A-B in which a second phase of introducing treatment is incorporated. There are some problems with A-B-A designs. The first problem is that the process ends with the baseline condition. Pedagogically speaking, educators expect that the effect of a treatment will continue over time rather than stop when the treatment is withdrawn. This problem can indeed be remedied by an A-B-A-B design in which a second round of treatment is added. The second problem with A-B-A design is that if the effect of treatment continues over the second baseline measurements, it would be hard to infer whether the continued effect is due to the treatment or other intervening or extraneous variables. Because of the problems with A-B-A designs and unless there is a particular reason for using this type of design, researchers may prefer to design and conduct either time-series or experiments depending on the purpose they define for their research project.

Figure A.1 A-B-A time-series design

Further reading → Ary, Jacobs, Sorensen, & Walker (2014), Bailey & Burch (2002), Johnson & Christensen (2012), Huitema & Laraway (2007), Kazdin (1982), Wiersma & Jurs (2009)

See also → baseline, experimental designs, extraneous variables, intervening variables, research design, time-series design

Abductive approach

Abductive approach is one of the principles in pragmatism and, in turn, in mixed-methods research (MMR), and refers to the relationship between theory and data. It involves a dialectical and iterative interplay between current theoretical frameworks and empirical data. In other words, abduction allows for relating case observations to theories or vice versa, which can result in more plausible interpretations and explanation of the phenomenon. Broadly speaking, in quantitative research, researchers usually aim at testing hypotheses pertaining to specific theories using a deductive logic or deductive approach, whereas in qualitative research the purpose is usually to generate hypotheses or theories using an inductive logic or inductive approach. In mixed-methods research because the purpose is to integrate both quantitative and qualitative approaches, researchers can move back and forth between theory and data using an abductive logic or abductive approach in favour of drawing more rigorous and comprehensive inferences about the issue being studied. A basic example of this back-and-forth movement between inductive and deductive approaches in mixed-methods research would be the case of a sequential mixed-methods design. In such a study, the researcher first generates some hypothetical explanations about a phenomenon from interviews with a small cohort of, for example, language teachers through an inductive and contextually based qualitative study. In the process of analysing the qualitative interview data, the researcher may look back at relevant theories in generating explanations or hypotheses from the interviews, thus establishing a back-and-forth movement between the data and theory. The results of the qualitative study achieved through an inductive data-driven approach but in light of relevant theories can then be used in a deductive theory–driven, larger-scale study. The hypothetical or theoretical constructs developed from the interviews in the first phase are used as the underlying constructs for creating a survey questionnaire that could be administered to a larger sample of participants. The survey research thus aims at investigating the credibility of the inductively developed, data-driven hypothetical constructs with a larger sample of participants. The results of the quantitative phase of the study can thus be used for generalisability purposes. Depending on the design of the mixed-methods research, different configurations of qualitative (inductive) and quantitative (deductive) combinations are possible. The abductive approach thus provides a context for researchers to make inferences to best explain the phenomenon by integrating exploratory and explanatory insights in a single project. It provides MMR researchers the possibility to expand the scope of their inquiry by systematically and interactively using both inductive and deductive approaches in a single study.

Further reading → Danermark et al. (2002), Haig (2005), Josephson & Josephson (1996), Locke (2007), Morgan (2008), Rozeboom (1999), Special issue of Semiotica (2005), Teddlie & Tashakkori (2009)

See also → credibility, data, deductive approach, hypotheses, inference, inductive approach, interviews, mixed-methods research (MMR), participants, qualitative research, quantitative research, questionnaires, research design, sample, sequential mixed-methods designs, survey research, theoretical framework

Absolutism

Questions such as whether there is universal truth, or that truth and knowledge are relative, or what constitutes knowledge have engaged the human mind from early stages in history and have resulted in absolutist versus relativist perspectives about truth and knowledge. Absolutism is used as a contrast to relativism, each representing a school of thought and denoting a different worldview or doctrine. From the perspective of absolutism, the physical and the social world are formed by many natural laws, which yield unchanging truths. On the other hand, a relativist perspective posits that there is not much difference between knowledge and belief and, as such, knowledge is a kind of belief constrained by individual and socio-cultural norms and thus changing across time and place. The debate between absolutism and relativism has implications for researchers and research methodologies and has nurtured the quantitative and qualitative debate. An absolutist researcher in both the natural and social sciences may thus attempt to discover the natural laws and seek truth-like propositions, which are time and context free and generalisable as universal laws. Logical positivism is a school of thought that can be matched with an absolutist worldview. Relativist researchers, on the other hand, recognise multiple realities and thus multiple truths and seek to understand how the same phenomenon may be represented and construed differently by different individuals or social groups. These two perspectives have for a long time led to the quantitative and qualitative paradigm wars and incompatibility thesis. A pragmatic approach toward research recognises both approaches and seeks for warranted claims. Warranted claims are conclusions drawn or inferences made from quantitative or qualitative data and analysis and an integration of them for a better understanding of the research problem. As such, the role of experts and intersubjectivity (consensus among thoughtful members of a discourse community) becomes very important.

Further reading→ Berger & Luckman (1966), Dewey (1929), Foucault (1977), Kuhn (1962), Teddlie & Tashakkori (2009)

See also → incompatibility thesis, intersubjectivity, (post)positivism

Abstract section of reports

Each research report usually comes with a summary of the entire project to help readers get an overview of the study being reported on. The abstract is, however, quintessential and a requirement for journal articles. Even though different journals may have different standards as how the abstract should be prepared, there is usually a consensus that the abstract of the papers submitted for publication should have four moves or include four parts. The first move usually states the research problem and the purpose of the study; the second move provides some brief explanations about the methods of the study, including participants and data collection and analysis procedures. The third move highlights the main findings of the study, and the final fourth move presents brief theoretical and/or pedagogical implications of the study’s findings. Because the abstract provides considerable information in a short space, it is therefore crucial to write it clearly and succinctly. The editors and reviewers’ first encounter and judgment of the paper will be based on the quality of the abstract. If the paper gets published, the abstract is indexed by indexing centres and will reach a wider audience when searching for any of the keywords related to the topic of the paper. The length of the abstract varies depending on the purpose for which the abstract is prepared, but journals usually urge writers to prepare an abstract within a range of 120 to 250 words. For a thesis, an abstract may have up to 300 words since there is more room for each section and chapter. There is usually a summary or an extended abstract of the study in the final chapter of the thesis, too, wherein the researcher/author will have a chance to provide more details and write a more complete summary of the study. Apart from theses and journal articles in which authors must write an abstract, conferences also seek abstracts from potential presenters. The role of an abstract in conferences may be more important because it is the only document on which reviewers decide whether the paper should be accepted for presentation in the conference or not. Like journals, some conferences provide some useful instructions of how to prepare the abstracts, as well as the criteria for judging the quality of the submitted abstracts. It is therefore a good idea to read carefully the instructions for preparing abstracts for conferences.

Further reading → APA (2010), Brown (1988), Brown & Rodgers (2002), Mackey & Gass (2005), Porte (2002)

See also → conclusions section of reports, discussion section of reports, procedures section of research reports, results section of research reports

Accidental sampling

See convenience sampling

Action research

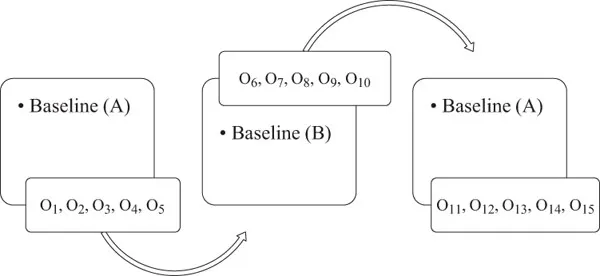

Action research aims at improving professional practice by bringing about change, often through involving research participants in the process of investigation. The action research may be conducted by a practitioner or in collaboration with a researcher. The essence of action research is the intervention in the functioning of an aspect of the real world (e.g., a classroom) to bring about a positive change, hence the term “action research”. The main purpose of action research is thus taking action to solve a local problem or to improve practice and not to generalise research findings. Action research is usually conducted by following certain steps in a cyclical or spiral way. The steps include problem identification, planning, acting, observing, and reflecting as depicted in Figure A.2. The process can lead to new cycles of action research depending on the reflections the researcher makes. As such, action research is also referred to as “reflection-in-action” especially when it comes to making changes in one’s teaching approach.

Figure A.2 Action research

The observation includes collecting data through different techniques such as, but not limited to, interviews, documents, diaries, field notes, and recordings of participants acting on the intervention. Results of the data analysis will lead to a better understanding of the problem, which might be used as a basis for further reflections and new cycles of action research. There are different types of action research, namely, collaborative action research, critical action research, classroom action research, and participatory action research. Action research in schools is also called teacher inquiry or practitioner research. The use of action research in teaching and learning creates a culture of reflection and change by questioning and reflecting on one’s own approach to teaching and to make necessary changes based on some research evidence. Some of the benefits of action research for teachers include professionalisation through the professional development of doing action research, developing teachers’ scholarship of teaching and learning, promoting reflection and using research-based evidence for making changes, encouraging research collaboration, and empowering teachers as researchers. One of the key benefits of action research is its capability to bridge the gap between theory and practice in different fields by using research methods to inform practice and bringing about positive changes. Like any other research, action research has its challenges too.

Further reading ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- The encyclopedia

- Further reading

- Index