- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

OPEC: Twenty Years and Beyond

About this book

Addressing the major issues arising from the power ascribed to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), this book reflects the bredth, expertise and multifaceted viewpoints of the contributors: members of OPEC itself, industry representatives, and scholars and energy specialists from the USA, Europe and the Middle East. Throughout the book, the authors look at the potential of OPEC, discernible trends in such crucial areas as global petroleum supply and pricing, and the international economic and political implications of both.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access OPEC: Twenty Years and Beyond by Ragaei el Mallakh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE WORLD ENERGY OUTLOOK IN THE 1980S AND THE ROLE OF OPEC

Introduction

History will record it was the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) that first drew attention to the energy problem. However, it was not until 1973, when OPEC assumed the administration of oil pricing, that the world suddenly became aware of the “depletable and nonrenewable” nature of the oil resource. In proclaiming the exhaustibility of a commodity which, because of its cheapness and seeming abundance, had been taken for granted — and consumed accordingly — OPEC confronted the world in general, and the oil industry in particular, with an entirely new situation, one for which it was ill-prepared and, at first, unwilling to accept.

Needless to say, in the prevailing circumstances of the time the OPEC message was not well received. Several statements addressed to the consuming nations underlined certain unpalatable truths: that the oil reserves were the rightful property not of the international oil companies but of the producer nations; that the oil, which was being pumped at ever-increasing speed and which represented for many of the producers their sole marketable asset, would one day, in the not too distant future, reach exhaustion; and that, as a depletable resource, oil is and had been all along underpriced.

History will also record that, following the initial unjustified violent reaction to OPEC’s message on the part of the consumer nations and their governments, the voice of reason began to make itself heard in the councils of the major industrialized consumers, and the whole question of future energy supply became an issue of first importance. This new “energy-consciousness” led to a more respectful attitude towards OPEC and its policies. It came to be realized, if only reluctantly, that the producers were talking sense; that both producers and consumers must take measures to prepare against the day when there would be no more oil.

OPEC’s case for reduced consumption; for accelerated exploration and exploitation of known and presumed reserves; for real efforts at conservation; and for a concerted drive to develop alternative sources of conventional and nonconventional energy in sufficient quantities to enable a gradual transition from oil to sources of a renewable nature — all these pleas increasingly began to fall on at least some receptive ears in the consumer countries.

The situtation today is but little improved on that which compelled OPEC’s intervention in 1973. Admittedly, the price of oil has risen, but is still nowhere near its true value in real terms. The rate of oil consumption, while having decreased noticeably in the current decade with respect to the past, is still markedly higher than that of coal. At the same time the reserves have not increased as in the 1950s and 1960s but, on the contrary, have been marked in this decade by a sharp decrease with respect to the past. The figures in table 1 illustrate this issue.

Table 1

CONSUMPTION VERSUS OPEC RESERVES

(in percent)

(in percent)

1950–1960 | 1960–1970 | 1970–1977 | |

Rate of oil consumption increase | 7.5 | 8.0 | 3.8 |

Rate of OPEC reserves increase | 13.0 | 7.7 | −1.1 |

Source: OPEC statistics.

This clearly indicates that exploration is not proceeding fast enough, while the exploitation of existing reserves of oil and gas, especially in OPEC member countries, is moving along quickly. Simultaneously, there is little evidence that genuine efforts at conservation are being made.

The purpose of this article is to examine the outlook for the coming years, with particular reference to the role of OPEC in its capacity as the traditional supplier of the bulk of the world’s crude oil. The study will deal briefly with the history of oil’s steady rise to become, in place of coal, the major source of energy, with its continuing predominance in the present day, and the emergence of serious interest in alternatives to oil. The article will also discuss the pricing mechanism of oil as a practical tool for the development and supply of other conventional and nonconventional sources of energy, and the need for governmental policies in consumer countries to encourage energy saving as well as legislation to implement conservation. The role of non-OPEC sources of oil and gas will also be touched upon, together with the delicate balance between supply and demand and the prospects of being able to achieve a smooth transition from oil to alternative sources of energy. Finally, proposals will be put forward whereby cooperation between OPEC and the consumers could lead to the world being able to avoid a potentially disastrous gap in that transitional period.

Oil versus Coal

Since the 1800s, the chief sources of the world’s industrial energy have been fossil fuels, mainly coal, oil, and gas, all of which are of a nonrenewable nature. A look at the cumulative consumption figures clearly reveals that although coal has been in use for about 1,000 years, half of the quantities produced so far have been mined since the beginning of the Second World War, while half of the world’s petroleum cumulative exploitation has occurred since 1956 only. Furthermore, the bulk of the world’s consumption of energy from fossil fuels has taken place within the last 40 years. Until 1900, the contribution derived from oil and gas as compared with coal was negligible, amounting to a mere 8 percent as opposed to 89 percent. In 1950, oil and gas increased their share from 8 percent to 34 percent, whilst coal decreased from 89 percent to 59 percent. In 1960, the rates were almost equally balanced, oil and gas occupying 44 percent of the total energy supply and coal 49 percent.

Thereafter, however, the contribution of oil and gas steadily increased; in 1968, the figures were: oil and gas 57 percent and coal, continuing its downward trend, 36 percent. By 1972, the oil and gas share had reached 63 percent, while that of coal went down to 31 percent. In 1977, coal and oil and gas occupied 30 percent and 62 percent, respectively, of total energy supply. Furthermore, the rate of increase in oil and gas consumption was greater than the rate of growth in energy demand, while the reverse was true of coal.

Table 2 illustrates the behavior of the growth of total demand of primary energy versus that of oil and gas and coal in the period 1950 to 1977.

Table 2

GROWTH OF TOTAL PRIMARY ENERGY DEMAND VERSUS OIL AND GAS AND COAL

(in percent)

(in percent)

1950–1960 | 1960–1970 | 1970–1977 | |

Total demand | 5.2 | 4.9 | 3.3 |

Oil and gas | 8.10 | 8.3 | 3.55 |

Coal | 3.5 | 1.0 | 2.00 |

Source: OPEC statistics.

A Cheap Resource

The reason why oil and gas resources came to occupy such a predominant place in the supply of energy is easily found: they were extremely cheap, easy of access, and unique in their scope of utility. It was hydrocarbons that provided the developed countries, through their command of the oil resources of the Middle East, with the cornerstone upon which they were able to build their industrial power. Indeed, for more than a quarter of a century after 1945, the nations of the West enjoyed a degree of uninterrupted economic expansion unparalleled in human history. One of the keys to the wealth thus generated was oil — oil in abundance and at ever lower prices.

From the producers’ point of view, however, this situation was untenable and could not be permitted to continue. Thus OPEC came into being.

After 1973, the attention of the world was focused, as never before, on the problems related to natural resources and energy. Both the strategies of OPEC member countries and the solemn warning of the Club of Rome were instrumental in awakening the world to the startling concept that natural resources were limited, thus inducing governments, private institutions, and others to give serious thought to the availability and future supply of hydrocarbons.

Oil Is Still Supreme

The structure and consumption patterns of industrial society being what they are, however, and given the present price of oil as compared with alternatives, the resource continues to occupy pride of place among the sources of energy. But for how much longer will oil rule the world? With present world proven reserves of oil estimated at 650 billion barrels, and present growth rates of consumption amounting to 22 billion barrels per year, the oil resource will dry up within the next three decades. In the case of gas, the picture is hardly any brighter. At present growth rates of consumption, the reserves, amounting to 71 trillion cubic meters, will last for another 45 years.

The present proven oil reserves within OPEC member countries now stand at about 450 billion barrels. If the present OPEC production level (30 million barrels per day) were to be maintained, OPEC’s output would start to decline at the end of this century, reaching exhaustion around the year 2025. Past and present estimates of ultimately recoverable reserves of oil and gas range extensively, but a reasonable consensus of opinion favors the figure of between 1,600 and 2,000 billion barrels, although some estimates, based on linear extrapolation of the past trend for the increase of such reserves, go as high as 4,000 billion barrels. However, further continued expansion on the same scale seems unlikely although there are good reasons for believing that, in time, expertise coupled with favorable economics will certainly allow additional resources to become recoverable.

With the estimated availability of additional conventional resources and the variety of unconventional sources of petroleum and gas, the age of petroleum could be considerably extended, enabling it to play a still important role in the transition to an energy economy based, hopefully, on renewable resources. It is with the conditions under which such a transition can be managed that today’s energy debate is primarily concerned. In this connection, it is naturally important to know how long can, or must, the transitional period last, and for how long can we rely on oil and gas resources during this period. Obviously, the ultimate aim must be to augment the age of petroleum in order to permit a real breakthrough in the development of alternative sources of energy, especially the renewable ones, so that these can be made available to the extent necessary and at reasonable cost as the nonrenewable resources dwindle.

Conventional and Unconventional Resources

To reach the above objectives, it will be necessary to achieve: (a) an increase in the hydrocarbon resource base by conventional and/or unconventional means; and (b) rapid development of alternative sources of energy, especially those of a renewable nature. With regard to the first prerequisite, it should be stated that regardless of what can be considered as an accurate estimate of the ultimately recoverable amount of hydrocarbons, the extent and availability of oil and natural gas, the fuller use of conventional resources opened up by enhanced recovery, and the possibility of exploiting hitherto untapped unconventional resources — these are all governed by the efforts made and the success achieved in solving the various technical, financial and political constraints which cause a significant hindrance to the rapid development of additional reserves.

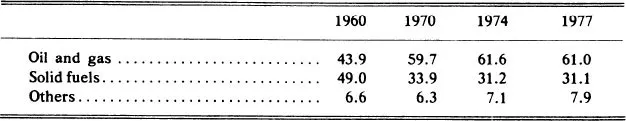

As far as the second prerequisite is concerned, due to the fact that prior to 1973 oil and gas prices were artificially maintained at unjustifiably low levels (which were just above the production costs in some areas), these exhaustible commodities — for some countries the only source of revenue — were undervalued for a considerable number of years and were over-consumed as if they were inexhaustible. Even following 1973–1974, when OPEC started to adjust its crude prices periodically, the previous pattern of consumption of the various fossil fuels continued to follow the same trend, whereby oil and gas were increasingly contributing to the world primary energy supply and coal behaving in the reverse fashion, as seen in table 3.

Table 3

OIL AND GAS CONTRIBUTION TO WORLD ENERGY SUPPLY

(in percent)

(in percent)

Source: OPEC statistics.

It is worth mentioning at this stage that OPEC’s 1973 decision, in addition to deriving a more adequate value for its exports, was aimed at giving an economic incentive to the development of alternative sources of energy. However, such development has not yet gained the momentum envisaged, and it may well be that the present price of crude is still too low to offer the required stimulus for this undertaking at a faster pace.

For about a quarter of a century, nuclear energy has been regarded by many as the natural successor to petroleum and gas in providing clean and safe energy sources. However, the perspective of atomic reactor proliferation is now generating widespread and deep concern with regard to safety, while costs are increasingly being challenged. Furthermore, due to the limited utilization of solar energy and the fact that efforts and financial support are slowly being devoted to this field, no real breakthrough is anticipated in the near future. Nonetheless, it is hoped that those countries with financial and technological capabilities will direct more attention to this area, thus enabling the energy supply system to be based no longer on hydrocarbons alone, but on a multiplicity of energy sources, in particular those of a renewable nature.

Extending the transition period requires far more than development of new supplies or diversification of resources; it also calls for practical intervention from the demand side. The demand for natural petroleum is a complex issue because it is affected inter alia by prices, by the development of alternative sources of energy and by the changes in end-use technology which take place slowly. Conservation of hydrocarbon resources entails the capacity to use these resources in such a way as to avoid waste and their exhaustion before alternatives become available.

At this stage it is worth giving some thought to the various practices and measures adopted by major consumers towards the hydrocarbon conservation issue. OECD countries, while adopting sound, long-term measures towards their indigenous resources (such as the restraint on production in the United Kingdom, Norway, and Holland, the limited well production policy in the United States, or the exploitation of coal in both Europe and America), fail to apply the same attitude and sound concept towards foreign supplies of these exhaustible resources.

The conservation measures adopted so far do not constitute a real concession to the exhaustibility of these resources. Studies carried out on the energy habits of consumer countries show the possibility not only of drastically reducing the wastage of energy, but also, more generally, of organizing energy systems different from the present ones, systems capable of integrating a multiplicity of sources, both old and new, using the materials available to the fullest extent.

In view of this, major consuming developed countries should pursue a more vigorous policy aimed at: (a) eliminating all forms of waste stemming from irrational uses of hydrocarbons; (b) revising production and transformation structures in order to eliminate sizable existing losses in conversion and transportation; and (c) integrating into the system other energy sources that can contribute to the energy balance. A rational approach for consuming hy...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. The World Energy Outlook in the 1980s and the Role of OPEC

- 2. Two Crises Compared: OPEC Pricing in 1973–1975 and 1978–1980

- 3. Some Long-Term Problems in OPEC Oil Pricing

- 4. Optimum Production and Pricing Policies

- 5. An Economic Analysis of Crude Oil Price Behavior in the 1970s

- 6. OPEC: Cartel or Chimaera?

- 7. The Oil Price Revolution of 1973–1974

- 8. OPEC and the Price of Oil: Cartelization or Alteration of Property Rights

- 9. Future Production and Marketing Decisions of OPEC Nations

- 10. Downstream Operations and the Development of OPEC Member Countries

- 11. OPEC Aid, the OPEC Fund, and Cooperation with Commercial Development Finance Sources

- 12. Oil Prices and the World Balance of Payments

- 13. Friends or Fellow Travelers? The Relationship of Non-OPEC Exporters with OPEC

- 14. The Future Relationship Among Energy Demand, OPEC, and the Value of the Dollar

- 15. OPEC Revenues and Inflation in OPEC Member Countries: A Fiscal Policy Approach

- 16. Inflation, Dollar Depreciation, and OPEC’s Purchasing Power

- 17. OPEC’s Role in a Global Energy and Development Conference

- Index