![]() Part I

Part I![]()

Introduction to Part I

Medical anthropology in Europe: shaping the field

Elisabeth Hsu and Caroline Potter

Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

‘Europe’ has been a point of reference for medical anthropologists previously (e.g. Lock 1986; DelVecchio Good et al. 1990; Pfleiderer and Bibeau 1991), and also in more recent years (e.g. Saillant and Genest 2007 [2005]).1 In this issue, ‘Europe’ refers to teaching and research at European Universities, and their intellectual outreach. To be sure, a ‘European’ as opposed to a ‘North American’ or ‘Japanese’ medical anthropology does not exist. Nor are there distinctive national styles of doing medical anthropology; diversity prevails even within a single language community. Rather, medical anthropology has emerged as an academic field on an international playing ground, and trans-Atlantic exchanges have always drawn on a serious engagement with research in Asia, Africa, Meso- and South America. Considering that medical anthropology is now taught in a rapidly growing number of graduate and undergraduate courses in Europe (Hsu and Montag 2005), while recently compiled anthologies honour almost exclusively authors working in North America (e.g. Good, Fischer, and Willen 2010), this publication may provide a cautious ‘corrective’ (naturally with no claim to representativeness of all medical anthropology in Europe).

When one works within such a dynamic field that is also very polymorph, questions arise about how it all began. Reflections on origins are always linked to issues of self-definition and future developments. This special issue of Anthropology & Medicine attends to questions about the past and future in two parts. In the first part, six pioneers in the field (all currently in retirement) speak about their experiences when they started research and teaching, some 40 to 50 years ago: Tullio Seppilli, Gilbert Lewis, Jean Benoist, Sjaak van der Geest, Armin Prinz, and Verena Kücholl/Münzenmeier. Their essays capture pieces of oral histories of the times when there was not yet a field as such.

The second part of the special issue attends to current issues, and its introductory paper – asking quo vadis? – aims to identify core themes that have defined the field from the early days to the present. It identifies ‘the practice of care’ as one of the most well-researched themes by medical anthropologists in Europe, and explains this in light of the well-known tension in medicine between competence and care. Accordingly, studies into medical care, which often contained an implicit critique of medicalisation, countervailed earlier studies into ‘the problem of knowledge’ – a theme of research that has since radically changed, both in theoretical orientation and method. Early preoccupations with knowledge have now been superseded by research into practice and ‘the body as a project in the making’.2 The six papers on current issues are presented in three sections (further detailed in the introduction to Part II), whereby each presents the work of a senior scholar alongside a more junior one. The volume thus presents work from across three generations of medical anthropologists in Europe.

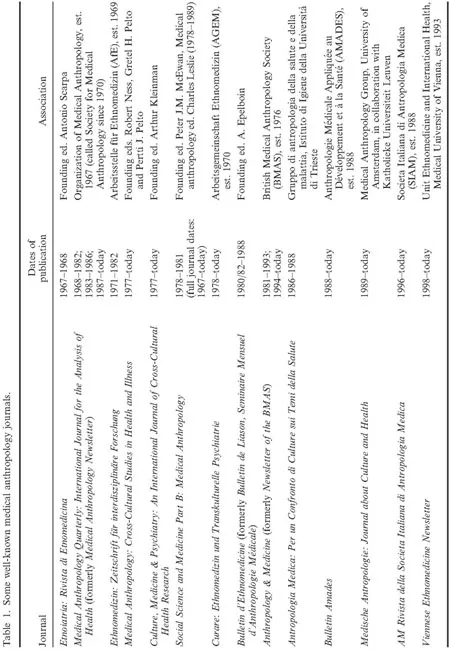

As Seppilli (this issue) demonstrates, an interest in a broader spectrum of themes relating to what is nowadays called medical anthropology can be traced back centuries and, in the twentieth century, as Van der Geest (this issue) shows, to tropical doctors’ confrontation with their patients’ health beliefs and practices in foreign countries. To these discussions others can be added, which highlight a distinctive point in time of striking convergences: the 1970s. The two essays on developments in Britain (Lewis this issue) and German-speaking countries (Kutalek, Münzenmeier, and Prinz this issue) demonstrate clearly that, during this formative period, the first interdisciplinary conferences were held on themes relevant to what was to emerge as a distinct field. The first monographs were then written, the first associations were founded (see vignette by Hardon and Beaudevin), the first journals were published (see Table 1), and the first university positions were established (both in anthropology departments and medical schools). In this respect, the history of the field in Europe was no different from that in North America.3

This phenomenon of the 1970s warrants an explanation.4 Surely, post-war ‘modern’ medicine had reached a peak of its professionalisation then, and physicians had a status of respect and authority that they no longer have in the twenty-first century. Medical sociologists were articulate in their critique and fed into sociology’s long-standing concern with ‘modernity’ and its trends towards normalisation and deviance, as initially discussed by Talcott Parsons and Erving Goffman. This sociological research, which was to have a profound impact on medical anthropology, was incorporated primarily – but not exclusively (e.g. Frankenberg 1980) – by way of the North American academy: Leslie’s (1976) and Kleinman et al.’s (1975) edited volumes are both concerned with the professionalisation of medicine, but in South and East Asia respectively (rather than ‘at home’).

The focus on professionalisation brought with it an interest in ‘health sectors’, ‘medical systems’ and ‘medical pluralism’. Of those, the first theme was to play a role particularly in public health research; the second instantly met with criticism, mostly by Africanists (e.g. Last 1981; Pool 1994); while the third, despite its bounded concept of culture and limited purview of power differentials in medical authority, has survived as a recurrent theme (e.g. the 2011 conference in Rome, organized by the EASA medical anthropology network).

However, the medical sociological orientations from North America met with another research interest then burgeoning at European universities: the study of social crises in medical terms, and their redress (see Lewis this issue). The description of society through the lens of crisis situations proved illuminating, as the workings of social institutions often go unnoticed otherwise; Turner’s (1968) discussion of village and kinship politics carried out in a medical idiom was an acknowledged precursor. Accordingly, the 1960s and 1970s saw not only the medical profession’s expansion and consolidation, critiqued by sociologists, but also the remarkable growth of and diversification in academic fields such as social/cultural anthropology, which responded to a rapidly changing world. The ethnographic documentation of acute crisis situations, and the social processes they instigated, appear to have laid the foundations for the field that we nowadays call medical anthropology.

Medical anthropologists have regularly engaged with research in public health and primary care, both abroad and at home. It is probably an achievement, even if sometimes feelings to the contrary arise, that the field has been able to accommodate a most heterogeneous group of researchers. Some Social Anthropology departments established tenured positions in medical anthropology, such as those in Cambridge, Amsterdam, Leuven and Copenhagen. In other places, the School of Medicine installed short-term training programmes for public health professionals intent on doing development work ‘in the tropics’, such as those in Heidelberg and Aix-en-Provence. In the late 1980s, the first master’s courses were set up, catering primarily to general practitioners interested in the socio-cultural aspects of the medical encounter, such as those in Oslo and Brunel. And finally, there are those centres that have done all three for over half a century, such as that in Perugia.

In Europe, as presumably also elsewhere, so-called ‘applied’ medical anthropologists are the most numerous, and for many medical anthropologists, this remit has been the field’s main strength (Helman 2006 – his introductory book (Helman 2007 [1984]) is now in its fifth edition and has been translated into several languages). Applied medical anthropologists’ comparatively high employment rates have come at a price, however. In some settings, Rapid Assessment Procedures (RAPs) and Participatory Rural Appraisals (PRA) have replaced language-competent, long-term fieldwork – deemed too unspecific, too time-consuming and too costly to be implemented in the light of the ‘urgent needs’ that medical practitioners alleviate.

Two themes, directly relevant to anthropology at home, have more recently marked the ‘applied’ field. Neither is extensively discussed in this volume, but they are briefly mentioned here by way of outlining the horizons within which this volume is situated. The first centres on changing notions of ‘citizenship’, constructed in relation to one’s biomedically defined and hence ‘biological’ status (Petryna 2002). This emergent research relates the biomedical to the legal and bureaucratic, often framing issues of morality in terms of human rights. Medical questions come to serve as vehicles for the wider political commentary (e.g., which lives to save during war; Fassin 2007). The second ‘applied’ theme concerns research into complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), otherwise mostly undertaken by health professionals in primary care. Not least in response to specifically post-socialist developments, Eastern European researchers have become particularly active in studying CAM, also as expatriates (e.g. Penkala-Gawecka 2002; Johannessen and Lazar 2006; Lindquist 2006). Their research converges in interesting ways with CAM research undertaken in Mediterranean countries and Portugal, which appears to have arisen out of a longstanding association with folklore studies, as evidenced in a recent volume on new age versions of age-old bathing cultures (Naraindras and Bastos 2011).

As the contributors to this special issue demonstrate, however, the field has always engaged in substantial theoretical developments, in addition to its value for people working in ‘applied’ structures. At this juncture of medical anthropology’s recent and ever-wider expansion in Europe, the authors call for a moment of reflection, so that we might position our current research endeavours in respect of our own past.

Acknowledgements

This special issue is based upon papers presented at the conference ‘Medical Anthropology in Europe’ funded by the Wellcome Trust and Royal Anthropological Institute.

Conflict of interest: none.

Notes

1. See also Diasio (1999) on central European developments and Ingstad and Talle (2009) on the Nordic network of medical anthropology.

2. Admittedly, the mind (and mental illness) rather than the body figured among the early core themes, but since the body is central to the medical anthropology programme at Oxford, where the RAI conference that prompted this special issue took place, it provided a thematic anchor.

3. European appointments in medical anthropology included those at Perugia (Seppilli, from 1956), Cambridge (Lewis, from 1971), Heidelberg and Zurich (assistant lecturers, from 1977), Amsterdam (Van der Geest, from 1978), and Aix-en-Provence (Benoist, from 1981). These initiatives broadly coincided with North American appointments at McGill (Lock), Harvard (Kleinman, Good) and UC-Berkeley (Leslie, Scheper-Hughes).

4. Beginnings in the 1970s appear to apply only to countries where social anthropology was already an established discipline of higher education. In socialist Croatia, biological anthropologists founded an anthropological society in 1977 and a ‘Commission on Medical Anthropology and Epidemiology’ in 1988, while possibilities for devel...