![]()

Overview

R. E. Brummett

Aquaculture as we know it in the early 21st century is a consolidation of more or less independent experiences. Pharonic carvings indicate that the Egyptians were cultivating fish at least 2500 years ago. The Chinese claim to have been growing fish for centuries. The Romans had fishponds (piscinae). In the 14th century, the emperor Charles IV ordered all towns to build fish ponds to produce food, enhance the local environment and protect watersheds. Paleolithic Hawaiian Islanders isolated embayments for rearing fish in the sea. Whatever the original objective of these aquaculture initiatives, from each evolved a set of concepts that until quite recently, strongly influenced how aquaculture interacted with local society and the environment.

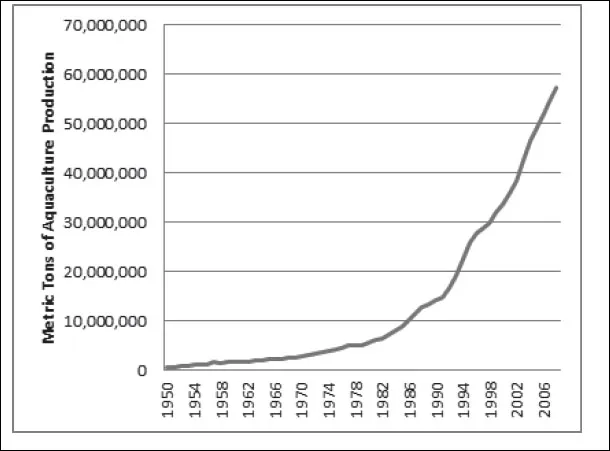

One could argue that modern, global aquaculture arose from these different local traditions only in the second half of the 20th century. Aquaculture began to gain critical mass and make noticeable contributions to fish supply in the 1950’s (Figure 1). Scientific evaluation of the integrated agriculture-aquaculture systems that had evolved in China began in the 1960’s. The publication of two books in the 1970’s, Traité de Pisciculture, Fourth Edition (Huet 1970) and Aquaculture: The Farming and Husbandry of Freshwater and Marine Organisms (Bardach et al. 1972) for the first time brought together for analysis and comparison the range of global aquaculture experiences. The World Aquaculture Society and the European Aquaculture Society were formed in the 1970’s. The journal Aquaculture began in 1972. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) began separate reporting of aquaculture statistics from capture fisheries statistics in the early 1980’s.

FIGURE 1 The nearly logarithmic expansion of global aquaculture was fueled by a close working arrangement between scientists and investors starting in the 1950’s.

These initiatives consolidated, or represented a consolidation of, the wide array of aquaculture systems that had grown in isolation from each other, the international research and development (R&D) community that has worked together with industry to solve problems and produce average annual industrial growth rates of about 10% over the last 15 years.

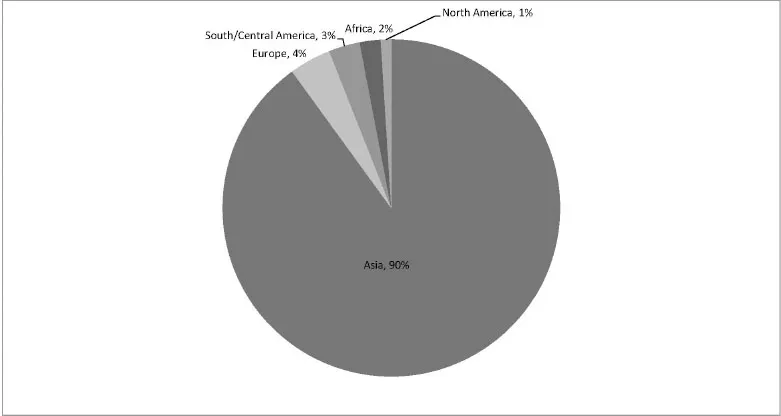

Aquaculture is predominantly an affair of less-industrialized economies (Figure 2). Despite the dominance of, particularly, Asia in terms of production and consumption, the technology that drives productivity and efficiency is derived from scientific research that is largely conducted and published in Europe and North America. Less than 20% of the world’s population lives in the countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) but out of the total of 139 257 engineering and technology papers published in 2007, almost 60% came from OECD countries (UNESCO 2010). Of the 47 574 patents granted by the Triad patent offices (the US Patents and Trademark Office, European Patent Office and Japanese Patent Office) in 2006, 96% were to researchers in the OECD.

FIGURE 2

In some cases, research and development are regarded as luxuries for industrialized economies and deprioritized in the budgets of less developed countries (LDCs). Without an indigenous and innovative scientific community to guide the development of new technology and the adaptation of old technology, less developed regions will never catch up with already industrialized ones. We can only imagine what could be achieved with the elimination of this waste of 80% of the world’s brainpower.

Aquaculture science in developing countries is largely and properly targeted towards the resolution of local problems. Even in industrialized countries, this kind of work is seldom of interest to scientific journals that seek to push theoretical boundaries.

In applied science, however, theory is only useful to the extent that it guides practical problem solving. Because it focuses on a field where LDCs have a clear advantage, aquaculture research can be a leader in over-turning the perception that science is the business of the already wealthy. The Journal of Applied Aquaculture has over recent years focused attention on the need to enhance the profile of practical aquaculture scientists working to solve real problems in the context of less developed economies by getting their research out into the public domain where it can be used to positive by other applied aquaculture scientists.

In this volume, we have brought together some of the outputs of this strategy from over the past three years. Papers from practical aquaculture scientists working in Latin America, Asia, the Middle East and Africa reflect the relative level of development of the sector in these regions and reveal the breadth of analytical, basic and applied research that is generating local solutions for global aquaculture.

As one might expect from the struggling aquaculture sector on the mother continent, papers from Africa focus on development policy and basic production systems, with an emphasis on small-scale aquaculture for rural food security. Herbert Ssegane in Uganda developed a geospatial model to guide local government prioritization of aquaculture in various parts of the country. Kitojo Wetengere and Viscal Kihongo in Tanzania examine the availability of credit that would allow smallholders to ramp up production to meaningful scale and finds that the rural poor cannot get credit because their production systems are too risky. Support to extension services and improved business planning are recommended as means to improve system reliability and profitability, thus making aquaculture farms more bankable. An aquaculture team at Cameroon’s Humid Forest Ecoregional Center explores the context of small-scale aquaculture development and finds that, like in Tanzania, quality of technical support to the aquaculture sector is problematic, but credit is less of a constraint than reliable access to feeds and good fingerlings. Overall, these constraints have constrained growth and prevented small-scale aquaculture from having any noticeable impact on rural poverty.

Focusing on African production systems, Melanie Hauber studied the dynamics and potential for improvement of the traditional whedo aquaculture system in Benin, concluding that concentrating technological innovation to enhance existing production systems would be more efficient than introducing foreign technology. Simon Tabero in Rwanda explores the productivity of integrated fish-rabbit systems, while Ofori et al. describe the economics of growing tilapia in cages in the Volta Lake, Ghana.

Water is a major constraint to aquaculture development in the Middle East, as reflected by contributions from this region. In Lebanon, Imad Saoud’s team at the American University of Beirut has been studying mixed fish and row crop production systems that can increase water use efficiency. In the United Arab Emirates, Nowshad Rasheed and Ibrahim Belal show how selective breeding can improve fish performance and water use efficiency in recirculating aquaculture systems. In Iran, Mohammadi et al. showed how underground brackishwater of limited use for other food production systems, can successfully be used in trout hatcheries.

The aquaculture sector in Latin America and the Caribbean is growing and the search is on for aquaculture candidates from among the thousands of indigenous fish species in the region. The giant pirarucu from the Amazon performs well in culture, but demands very high protein feeds, so a team in Brazil looked at blood meal as an alternative. Already produced in some quantities, variability in growth performance in jundia catfish lead Luciano Augusto Weiss and Evoy Zaniboni-Filho at the Federal University of Santa Catarina to test the feasibility of using triploidy technology to improve consistency. In Mexico, aquaculture is seen not only as a means of growing aquatic animals for food, but also for restocking and a group led by José Luis Arredondo-Figueroa at the Autonomous University of Metropolitan Iztapalapa is developing culture techniques for the indigenous acocil crayfish.

Coping with over-stress land and water resources is a leading theme in contributions from crowded Asia. Indian scientists in the Eastern Himalayas are working to develop more efficient integrated farming systems that combine crops, land animals and fish. Archana Sengupta from the Vivekananda Institute of Medical Sciences describes how fishers in heavily polluted Kolkata are using aquaculture to make money while improving local water quality. In Malaysia, Zainoha Zakaria leads a team that is looking to replace fishmeal with prawn processing wastes, while in Vietnam a team at Stapimex, one of the country’s leading seafood companies, establishes guidelines for the use of antibiotics in prawn culture.

Taken together, this selection of papers from the Journal of Applied Aquaculture exhibits the range and sophistication of the research being carried out to support the continued expansion of the world’s fastest growing food production sector. The editorial board and publisher of the journal will continue to work with these scientists as they push the boundaries, and make their good work better available to the global aquaculture community.

References

Bardach, J.E., J.H. Ryther and W.O. McLarney. 1972. Aquaculture: the farming and husbandry of freshwater and marine organisms. Wiley-Interscience, New York, USA.

FAO. 2012. State of world fisheries and aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Huet, M. 1970. Traité de Pisciculture (4th Edition). Editions Ch. De Wyngaert, Brussels, Belgium.

UNESCO. 2010. UNESCO science report; the current status of science around the world. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris.

![]()

Constraints in Accessing Credit Facilities for Rural Areas: The Case of Fish Farmers in Rural Morogoro, Tanzania

KITOJO WETENGERE1 and VISCAL KIHONGO2

1Centre for Foreign Relations, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

2Institute of Social Work, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

This study examined constraints in accessing credit facilities for fish farmers in rural Morogoro, Tanzania. Data was collected using techniques of participatory rural appraisal and secondary information sources. A descriptive statistics method was used to report findings, and data were validated by mean percentages and group consensus. This result revealed that farmers earned an average income per capita of Tshs. 56,666 (US$38) per year. Due to low profitability and high risk, most farmers were reluctant to invest their meager income in fish farming. Only 8% of respondent’s accessed credit facilities. Constraints to credit access included lack of information, unfavorable terms, lack of support services, and illiteracy. Research should focus on how to improve the profitability and reduce the risk of fish farming to attract bank lending in the industry.

INTRODUCTION

Poverty in Tanzania is overwhelmingly rural (United Republic of Tanzania [URT] 2005; Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics [TNBS] 2009). Poverty is highest among households that depend on agriculture (URT 2005). In rural Morogoro, poverty is manifested by people’s inability to produce enough food and income to meet household needs (ALCOM 1994). Farmers need to increase farm productivity in order to improve household food and income security (Wetengere 2010a). To meet rapidly growing food demand and raise rural incomes, farmers must intensify their farm production system (Delgado et al. 2003; Wetengere 2008b, 2010b).

Farmed fish is one of the high-value crops that can be intensified to meet household needs (Wetengere 2008b, 2010b). Despite the high potential for fish farming, a low level of technology has been practiced in Morogoro (Wetengere 2008b, 2010b), characterized by small ponds likened to holes, low stocking density, poor-quality seed, and low inputs in terms of management, labor, feeds, and fertilizers (Wetengere 2008a, 2008b, 2010b). Limited capital and/or lack of access to credit to purchase inputs constrain intensification (Kudi et al. 2009; Mikalitsa 2010; Wetengere 2008b, 2010b).

Although the subject of credit for rural development has been widely examined by, for example, Masawe (1994), Shastri (2009), Kudi et al. (2009), Fansoranti (2010), and Mikalitsa (2010), there are few studies (Johnson 1993; ALCOM 1994; FAO 2000; Wetengere 2008b) that have investigated the availability of credit for development of rural fish farming. The objective of this study, therefore, was to make a thorough investigation of constraints in accessing credit facilities for fish farming in rural Morogoro, Tanzania.

METHODS

The data used in this study are part of a market survey conducted in April–May 2006 in 24 selected villages in the Morogoro region of Tanzania. A field survey design that focuses on individual farmers as the unit of analysis was employed. This method is capable of capturing existing perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and values of individuals within a household (Mugenda & Mugenda 1999).

The study population consisted of fish farming adopters (women and men). From each village list, a systematic random sampling approach was used to select the respondents in order to avoid conscious or unconscious biases in the selection of sampled households and to ensure that the selected sample was representative of the entire population. In total, 217 farmers were selected for ...