![]()

Teacher educators and 'accidental' careers in academe: an Australian perspective

Diane Mayera, Jane Mitchellb, Ninetta Santorob and Simone Whitea

While teacher education is often seen as the key to preparing qualified teachers who are able to educate students for the demands of the twenty-first century, relatively little attention is paid to the teacher educators who actually do this work. Given the increased demand for teacher educators in Australia due to retirements, and the changing political and institutional context of teacher education, it is timely to understand a little more about the teacher educator workforce. Who are they, why do they work in teacher education, what career pathways have led them to teacher education, what are key aspects of their knowledge and practice as teacher educators, and what are the critical issues faced by those working in teacher education? This paper reports on a study that investigated the pathways into teacher education and the career trajectories of a small group of teacher educators working in a range of university sites in three states in Australia. The study draws on interview data to examine the ways in which these teacher educators talk about the accidental nature of their career pathways, their views about teaching and research, and the variable ways in which experiential and research knowledge are recognised and valued within the field of teacher education and in the academy. The report highlights important considerations for the preparation of the next generation of teacher educators as well as for their induction, mentoring and career planning in order to build and sustain a viable teacher education workforce for the twenty-first century.

Introduction

Literature about the nature of teacher educators’ career trajectories and pathways is relatively rare within the field of teacher education research in general, and specifically in Australia. A great deal of teacher education research has focused on teacher standards and competencies, professional experience and professionalism, and transitions to teaching. Of the 215 articles considered in a review of research pertaining to teacher education (Murray, Nuttall, and Mitchell 2008), only eight were concerned with the background, knowledge and attitudes of teacher educators, including both university and school-based teacher educators. Teacher educators are ‘a unique – but often overlooked or devalued – professional group with distinctive knowledge bases, pedagogical expertise, engagement in scholarship and/or research, and deep rooted social, moral and professional responsibilities to schooling’ (Murray, Swennen, and Shagrir 2008, 41). However, it is only very recently that the field has produced a small, but growing body of literature concerned specifically with the work of teacher educators and the need to understand their pathways into teacher education, their work experiences, and their aspirations and career trajectories. Such interest is derived from acknowledgement that in similar ways to how teachers and teacher quality affect school students’ educational success, teacher educators are increasingly being seen as key to the successful preparation of future generations of teachers. In addition, increasing concern about the ageing nature of the teacher educator workforce and the need for renewal has prompted research into the nature of the work of teacher educators and their professional identities. It is predicted that in the next few years in Australia there will be a shortage of academics in all disciplines (Hugo 2008). ‘[T]here is a clear, present and growing demand for academic work, a demand being propelled by system growth, looming retirements and increased international mobility’ (Coates et al. 2009, 2). The predicted shortage of academics is particularly worrying given the Australian Government target of 40% of those in the 25–34-year-old age group to have a bachelor’s degree or above by 2025 [Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) 2009]. Within universities, faculties and schools of education are potentially under great staffing stress, with 62.8% of the teacher education workforce currently over 50 years of age (Hugo 2008) and therefore eligible to retire within the next 5–10 years (see also Australian Council of Deans of Education 2009). In order to replenish and renew the teacher education workforce in Australia, it is important to understand who teacher educators are, what attracts them to teacher education, and what facilitates their career development and satisfaction. This study set out to address these questions.

This paper reports on a study investigating the career pathways and work experiences of teacher educators in Australia, highlighting why and how they became teacher educators; how they negotiate(d) academe, how they think of their work and themselves as teachers and researchers, and the variable ways in which their teaching experience and research knowledge are recognised and valued within academe. The paper provides an overview of past and present contexts of teacher education in Australia, outlines the study and methodology, and discusses two key themes that emerged from analysis of the data: (1) the entry of the participants into teacher education was often by accident rather than design; and (2) the participants held contested views of the knowledge required of teacher educators and the means by which that is gained. Recommendations are made for the preparation of the next generation of teacher educators and the induction, support, mentoring and structured career pathways that will be necessary to sustain their work in the increasingly politicised and performance-based culture of higher education in Australia.

The context of teacher educators' work in Australia

Significant contextual shifts have shaped the patterns of teacher education in Australia over the last 50 years (for details see Polesel and Teese 1998). These shifts have in turn influenced the career pathways and work of teacher educators. Teacher education in Australia in the early 1960s was predominantly located in teachers’ colleges controlled by state-based departments of education. Changes to the policies governing professional and technical education in the 1960s and 1970s resulted in the development of teacher preparation institutions independent of state departments of education and a new sector of professional higher education known as ‘colleges of advanced education’. This shift reflected a concern to improve the quality and professional standing of teaching qualifications. More broadly, it reflected a concern to develop national systems of professional and vocational education that modelled some of the structures of universities, attracted well-qualified teaching staff and offered degree-level courses. That said, there was a clear delineation made between these colleges and universities. Universities had a role in generating knowledge through research while colleges had a much stronger professional and vocational orientation. Thus, through the 1970s and 1980s the bulk of teacher education took place in colleges of advanced education, with a small number of universities offering postgraduate programmes in secondary teacher education. During this time the qualifications expected of a teacher educator were typically at least a degree higher than that those required by teachers, and/or outstanding teaching credentials.

The late 1980s marked another major shift, with the development of a unified system of higher education in Australia. The two-tiered college and university system became one. Through various processes of college amalgamation, mergers with existing universities and individual institutional change, a new and revised set of universities was established. This meant that all teacher education programmes were located within universities and led to considerable change in work orientation for those in the new university-based faculties and schools of education. As might be expected, these new universities also had responsibility for research and knowledge production alongside professional preparation of teachers. This had major implications for teacher educators in that they were now expected to have higher degree qualifications and engage in research alongside teaching. In the Australian higher education system it is increasingly difficult to gain a full-time, continuing academic position without a doctoral degree, and such a qualification is often expected for an entry-level lecturer academic position. Those employed in the Australian higher education system are promoted through tiered academic levels of appointment from lecturer to senior lecturer, associate professor and finally professor. Promotion is generally based on performance in three areas of academic work – research, teaching and service – although increasingly there is greater opportunity for staff to be promoted based on either research or teaching accomplishments.

Australia is currently in the midst of a national policy push that aims to improve teacher quality, and acknowledge the role of teacher education in providing high-quality beginning teachers. However, as in the case of many so-called developed countries, teacher education is being positioned as a ‘policy problem’ (Cochran-Smith and Fries 2005). The ‘Smarter Schools – Improving Teacher Quality National Partnership’ (TQNP) programme aims to develop and implement initiatives to attract, prepare, place, develop and retain quality teachers and school leaders in schools. This includes a push for nationalised and standardised professional standards for teachers, national accreditation of teacher education programmes and national registration of teachers, along with generously funded ‘alternative pathways’ into teaching, such as ‘Teach for Australia’, which implicitly question the value of teacher education as it has traditionally been delivered.

Another major consideration in Australian higher education is the perceived value of teacher education research and the research that teacher educators conduct and publish. Within the current political context, the value of teacher education research is being questioned. In Australia, as in many other countries, major research grants are rare in the field of teacher education and as a result teacher educators often study their own teaching and their own programmes, producing a wide variety of studies that include many small-scale and often unconnected studies of practice. From reviews of this research, teacher educators and others have learnt a great deal about the curriculum of effective teacher education, which includes coursework, field experiences, assessment and pedagogical approaches (e.g. Cochran-Smith and Zeichner 2005; Wilson, Floden, and Ferrini-Mundy 2002). However, as Grossman (2008) highlights, ‘as researchers and practitioners in the field of teacher education, we seem ill prepared to respond to critics who question the value of professional education for teachers with evidence of our effectiveness’ (13). Successive reviews of teacher education and teacher education research in Australia have come to similar conclusions (e.g. Australian Council of Deans of Education 1998; Committee for the Review of Teaching and Teacher Education 2003; Department of Employment Education and Training 1992, 1993; Senate Employment Education and Training References Committee 1998). Given the national policy push for alternatives to traditional teacher education pathways and questions about the value of teacher education, teacher educators must be prepared to respond to concerns with evidence of the effectiveness of teacher education and the value it adds, including a specific focus on the work of teacher educators.

Thus, over the past four or five decades there have been structural and conceptual shifts in teacher education; from training to education; and from a technical to an academic emphasis. These changes have had major implications for the career pathways and practices of teacher educators. Moreover, given the increasing government attention to the role of teacher education as it is currently offered, it is timely to examine the work of teacher educators.

Methodology

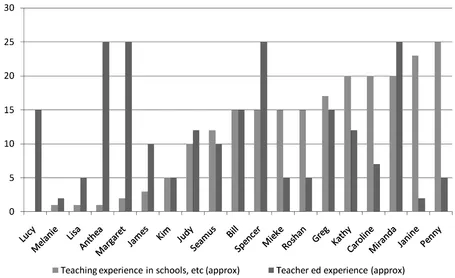

This qualitative study used a case study approach to investigating the career pathways and experiences of 19 teacher educators working in universities in three states of Australia: Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales. All teacher educators interviewed at the time were employed as full-time academics. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews that aimed to elicit information about the interviewees’ pathways into teacher education, challenges and career achievements, and their perspectives on the role of a teacher educator, including how they regarded themselves as researchers and/or teachers in the higher education context. Purposive sampling techniques were employed in order to build a participant profile that reflected diversity in terms of experience and institutional location. Thus, participants were selected from a range of institutional types in Australia: regional, metropolitan, established universities with a research intensive focus, and newer universities with an emerging research profile, as well as universities born out of the amalgamation of teachers’ colleges. We also selected participants with varying lengths of experiences within university and schools and other teaching contexts, as well as participants with and without doctoral qualifications. The 14 female and five male participants ranged in age from mid-30s to early 60s, with the majority being in their mid-50s. In this respect, most participants had considerable work experience, be it teaching in a school or in a university (average approximately 23 years). As Figure 1 details, the participants had varying amounts of school teaching experience, ranging from less than one year to 25 years. Likewise, the participants had varying amounts of experience as a teacher educator, ranging from one year to 25 years. With the exception of one participant, all had some school teaching experience prior to becoming teacher educators. The different levels of experience enabled aspects of their career pathways to be considered in relation to the contexts and changes in teacher education and higher education in Australia over the last 30 years.

Figure 1. Participants’ years of experience as school teachers and teacher educators.

All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and returned to participants for verification, and are represented here with pseudonyms.

Analysis of research data, like all aspects of the research process, is shaped by researchers’ own positionings and histories. This study was conducted by four mid-career teacher educators working in two different universities, each a large multi-campus provider of teacher education and each in different Australian states. Collectively, the authors have been teacher educators for 52 years (Ninetta 15, Simone 15, Jane 16, Diane 21). All completed their doctoral qualifications while working as teacher educators and have had varying amounts of school teaching experience. For example, Ninetta taught for 11 years in secondary schools and adult education contexts before coming into the field, Jane taught for four years in secondary schools, Diane taught for 13 years in p-10 settings, and Simone taught for six years in primary schools. The interview questions were shaped by the authors’ knowledge of the teacher education field and their understanding of what constitutes the work of teacher educators. To some degree, the authors’ careers were reflected in the stories of some of the interviewees, and how they understood and interpreted the data includes who they are, and what experiences they bring to the research.

Data were analysed using a thematic approach, whereby close readings of the interview transcripts were made in order to identify common themes across participants’ recounted experiences. This paper reports on two main themes that emerged. The first was the unplanned nature of teacher educators’ career pathways, with many participants acknowledging their entry into the profession as ‘accidental’. The second is related to participants’ perceptions of the knowledge required to work in teacher education; how that knowledge is generated and valued; how it links to a researcher/practitioner binary; and how that binary has been negotiated by participants over time.

Becoming a teacher educator: the 'accidental' career

Entering the teacher education profession often appears to be a phenomenon of chance. The teacher educators in this study generally came directly from working as teachers and had extensive experience in either primary or secondary schools, but did not have doctoral qualifications. A few came with minimum school teaching experience and with higher degree qualifications and research expertise. However, regardless of their pathway, all participants in this study spoke about how they ‘fell into’ teacher education. For example, Spencer, who has been a teacher educator for more than 20 years, encapsulates what many described: ‘It was an accident ... it was not an active decision. It was one of those things that I just fell into’. Bill, who is in his mid-4...