![]()

INTRODUCTION

Water management and climate change, their numerous interlinkages and the extent of their hydrologic, economic, social and environmental impacts over time and space are complex issues that can be predicted at our present state of knowledge only with a great deal of uncertainty. Lack of scientific understanding of the complex and interacting interrelationships and absence of reliable data are only two of the factors which prevent our forecasting likely future multidimensional and multisectoral impacts with any degree of accuracy. This, in turn, makes proper planning and investment decisions in a cost-effective and timely manner a most challenging task, even under the best of circumstances.

It is widely recognized that at the present state of knowledge, there are a number of important uncertainties in predicting the impacts of climate change in the water sector. These include but are not necessarily limited to: estimating future emission scenarios; analyzing them for greenhouse gas concentrations; predicting how these are likely to affect future global, regional and local rainfall patterns; interpreting their overall impacts on the hydrologic cycle at different scales; and assessing their impacts.

At present, it is still not possible to predict even how the annual average temperature in various regions of the world may change, let alone the rainfall pattern. Additionally, the latest generation of models to forecast average rainfall at the river basin and sub-basin levels have to be considerably improved before they can be used for water resources planning and management purposes. For water management, the problem becomes far more complex, because it must deal not only with the average changes in annual rainfall on the basin or sub-basin scale but also, and more importantly, with extreme rainfall events like serious floods and extended drought. The magnitude of the uncertainties increases several-fold when attempts are made to forecast extreme rainfall events based on increases in annual average temperatures, and even more when rainfalls have to be translated into river flows. In spite of these uncertainties, however, the overall perception is that climate change is responsible for nearly every serious flood or drought the regions and countries have witnessed in recent years.

In the final analysis, efficient water management over the long term requires reliable data and information, as well as understanding – both of the present and of expected events in the future. Historically, water infrastructure has been designed, and will continue to be designed (at least for the next several decades), on the basis of forecasts of future extreme rainfall and river-flow events that will continue to require past data and historical information. In the absence of better and more reliable estimates of expected future extreme rainfall events than the ones now available, the objective may have to be to continue constructing all types of new water infrastructure with the best knowledge available, and maintain and operate existing structures more efficiently in the event of prolonged droughts or serious floods.

To plan successfully and manage the increased uncertainties posed by likely future climate change, knowledge needs to advance much more for the water profession beyond what it is now available. Meeting these challenges does not depend exclusively on advances in climatological-hydrologic models. Policies for adaptation and strategies for mitigation measures have to be formulated on the basis of what are likely to be the potential impacts. These will have to be regularly fine-tuned and implemented according to changing needs and as more reliable knowledge and data become available. Even more challenging will be the politics of policy making and implementation, which will require a quantum leap from current policy-making and implementation processes. One can even say that, in addition to the development of more reliable models, the politics of climate change and water management remains one of the greatest uncertainties for the water profession.

To address the challenges and uncertainties related to water management and climate change, the Aragon Water Institute and the International Centre for Water and Environment of the then Ministry of Environment of Aragon, the Third World Centre for Water Management in Mexico and the International Water Resources Association jointly organized a meeting on “Water Management and Climate Change: Dealing with Uncertainties”, held in Zaragoza, Spain, from 28 February to 2 March 2011.

Well-known international experts in the field of water management and climate change were specially invited to discuss future-oriented issues such as: water management practices and how these should and could be modified to cope with climatic and other related uncertainties over the next two to three decades; the types of strategies and good practices that may be available or have to be developed to cope with the current and expected uncertainties in relation to climate change; and the types of knowledge, information and technological developments needed to incorporate possible future climate change impacts within the framework of water resources management. Decision making in the water sector under changing climate and related uncertainties, and societal water security under altering and fluctuating climate, were two matters that were also discussed in depth. Several case studies were presented from basins, cities, regions and countries, such as the Ebro Basin and the Himalayas; the Aragon and Catalonia regions in Spain and the state of Gujarat in India; the city of Zaragoza; and countries such as Australia, Greece, Mexico, Singapore, Spain and the Netherlands. The session also addressed the implications climate change may have for agriculture in India and in OECD countries.

The papers were extensively reviewed by the authors and are now included in this thematic issue. Nevertheless, with the objective to give them further dissemination, these papers have been available on-line for several months on the journal’s website: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/cijw20/current. To further contribute to global discussions on climate-related topics, this thematic issue also includes two state-of-the-art reviews. One of them addresses water and disasters and provides an in-depth review and analysis of the policy aspects; the second focuses on management of drought risks in European water-supply systems.

Finally, we would like to once again invite the academic, research, policy and water and development communities to further question, debate and challenge prevailing wisdom; we believe this is the only way to promote the advancement of knowledge.

Cecilia Tortajada and Asit K. Biswas

Editors-in-chief

![]()

Adapting to climate change: towards societal water security in dry-climate countries

Malin Falkenmark

SIWI and Stockholm Resilience Center, Stockholm, Sweden

Water security needs priority in adaptation to global change. Most vulnerable will be the semi-arid tropics and subtropics, home of the majority of poor and undernourished populations. Policies have to distinguish between dry spells, interannual droughts and long-term climate aridification. Four contrasting situations are distinguished with different water-scarcity dilemmas to cope with. Some countries, where the climate is getting drier, will have to adapt their water policy to sharpening water shortage. In many developing countries it will be wise to go for win-win approaches by picking the low-hanging fruit, i.e. taking measures needed in any case. A fundamental component of adaptive management will be social learning to help people recognize their interdependence and differences. Rethinking will be needed regarding how we manage water for agricultural production, integrating solutions with domestic, industrial and environmental uses. Adaptation to global change will benefit from basin management plans, defining medium- and long-term objectives. Conceptual clarity will be increasingly essential. Water – so vital in the life support system – needs to be entered into climate change convention activities.

Political stability, economic equity and social solidarity are very closely related to water, its management and governance. Hence the future should be viewed through a “water” lens.

Global Water System Project (GWSP, 2011, p. 6)

Introduction

At the Second World Water Forum, in The Hague in 2000, the Ministerial Declaration declared a goal of providing water security in the twenty-first century, in the sense of “ensuring that freshwater, coastal and related ecosystems are protected and improved; that sustainable development and political stability are promoted, that every person has access to enough safe water at an affordable cost to lead a healthy and productive life, and that the vulnerable are protected from the risks of water-related hazards” (quoted in GWSP, 2011, p. 3). Safeguarding societal water security has two basic dimensions: on the one hand to meet water needs in their relation to socio-economic production; and on the other to limit water-related risk, primarily in situations of flood and drought, to an acceptable level.

Large-scale emission of greenhouse gases has been warming the atmosphere, increasing sea evaporation and thereby exacerbating the warming through the additional greenhouse effect from increased atmospheric water vapour (GWSP, 2011). This has lead to changes in precipitation patterns, increasing their intensity and variability. Global warming is in other words speeding up the hydrological cycle, while land use changes alter the rainwater partitioning at the land surface between the blue and green branches, i.e. what goes to rivers and groundwater as opposed to what goes to the vegetation. The outcome is alteration of all the different hydrological elements: precipitation, evaporation, river flow, lake levels and groundwater recharge.

However, the real challenge is not the proceeding climate change alone but coping with global change after also incorporating other fundamental driving forces: the ongoing population growth that adds some 80 million people every year to the world population; the effects of socio-economic development and the increasing water expectations that it involves. In terms of its implications for water requirements and pressure on the available water, Vörösmarty, Green, Salisbury, and Lammers (2000) have shown that population growth dominates greatly over climate change as a driving force towards water scarcity. One should also remember that most of the population added will in fact be living in urban areas, as a consequence not only of population growth as such but of rural push and urban migration of poor rural inhabitants, leading to greater demands on water services, changing diets, etc. All these changes are in reality moving targets and interlinked in a nexus of ongoing change that policy makers have to navigate.

Achieving water security involves the twin goals of reducing the destructive potential of water and increasing its productive potential (Gray & Sadoff, 2007). How will global change influence the water management situations in different parts of the world? What main differences are there in vulnerability predicaments? And what steps are there to take for a country in adapting to the ongoing climate change and safeguarding their particular water security?

This paper will have its focus on climate change implications as regards the role of water deficiency for water security, and how to cope with them. Special care will be taken in terms of the distinction between water scarcity and drought, in line with the recent Dakar recommendation (INBO, 2011).

Critical vulnerability differences

Fundamental differences in exposure

Hydroclimate exposure differences

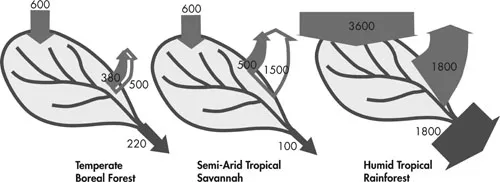

Most critical in terms of life support conditions, besides temperature, is the relation between precipitation and atmospheric uptake capacity (potential evapotranspiration). Figure 1 illustrates core differences in water balance between three main climatic zones: the temperate zone, where most of the advanced industrial economies have developed; the semi-arid zone, where the majority of poor and undernourished live (approximately one billion, of which around 450 million depend on rainfed agriculture); and the humid tropics, which host a series of emerging economies. All the zones are exposed to increased rainfall variability. Most exposed to water deficiencies, however, will be the semi-arid tropical zone, in view of the large water requirements for food production.

Figure 1. Fundamental water balance contrasts between three different hydroclimatic zones (units are mm/yr).

The Ministerial Declaration at The Hague referred to earlier reflects the insight that basic water security is vital for a country to be able to enter the path towards socio-economic development. Already at early development stages, countries strive for water storages to compensate for their sensitivity to drought. Gray and Sadoff (2007) have observed vital differences between those that have harnessed their hydrology by water storages etc. (see Figure 7, described later), i.e. mainly industrial countries; those that are hampered by their hydrology (Lundqvist, 2010), partly by flood events, droughts and water pollution, i.e. mainly emerging economies; and those that remain hostages of their hydrology, mainly poor developing econo...