![]()

Public–Private Partnerships: Infrastructure, Transportation and Local Services

GERMÀ BEL*, TREVOR BROWN** & RUI CUNHA MARQUES†

*Department of Economic Policy and World Economy, Universitat, de Barcelona, Spain; **John Glenn School of Public Affairs,The Ohio State University, USA; †CEG-IST, Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal

ABSTRACT Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are arrangements between government and private actors with the objective of providing public infrastructure, facilities and services. Three fundamental questions frame the use of PPPs at the local level: What do PPPs look like? What gives rise to the use of PPPs? And, what are the outcomes of PPPs? The articles in this symposium provide insightful answers to these questions. In addition, the symposium contributions identify lines of research that invite further investigation, namely: problems related to the degree of risk transfer; the challenges posed by renegotiation; and evaluation of PPPs’ results.

Introduction

When local governments produce and deliver big, complex goods and services, like road networks or water treatment and distribution systems, they increasingly enter into big, complex arrangements. These complex ventures are commonly referred to as public–private partnerships (PPPs). They usually take the form of a contractual agreement between the government and the private partner (contractual PPPs), in what can be seen as an extension of the standard procurement method, contracting out, which has evolved to include high-powered incentives. This requires transferring risk from the government to the private partner, in order to address traditional problems with moral hazard and quality measurement. PPPs can also adopt an organisational form (institutional PPPs), as the government and the private partner may share ownership of an organisation that is in charge of providing the infrastructure, the facility or the related services.

In the typical PPP, a government authority and a private entity agree to what at first glance is a fairly straightforward transaction: each party agrees to play a part in the production of the good or service for some amount of compensation. PPPs, though, involve an important twist on a conventional public sector exchange: the private entity assumes a higher level of financial, technical or operational risk than they do in a straight exchange contract, and in doing so, stands to reap a significant payout or stream of income if the project bears fruit. The financing of the project is often split between the private entity and the government. In this way, both sides pool their resources to invest in the project, hence the ‘partnership’ moniker.

As governments face the wicked combination of increased service demands and diminished resources, the use of PPPs has skyrocketed globally, particularly at the local level (Hodge et al. 2010). Local governments and private entities have increased and expanded the use of PPPs on the basis of what appear to be deals ripe with win–win possibilities: local governments win by being able to deliver to their citizens a good or service for which they lacked the financial, technical or operational capacity to produce on their own; the private partners win by investing in potentially lucrative projects at a lower risk than if they had been the exclusive investor. However, similar to what has been found in the recent literature regarding privatisation of local public services (see Bel et al. 2010), concerns with the outcomes of PPPs are important, because not all, in fact not many, PPPs have delivered on that win–win promise (Hodge and Greve 2007). Of particular concern is the use of PPPs as a governmental tactic to overcome the inability to fund public services with budgetary resources and/or user fees, thus envisioning the PPP as a financial tool for service provision. The increased use of PPPs and the lack of consistent win–win outcomes beg for scholarly inquiry.

This symposium examines the use of PPPs to produce and deliver public goods and services at the local level. One of the advantages of a symposium is comparative power, the ability to tap into scholarly economies of scale and scope. In this symposium we bring together scholarship on PPPs for a variety of different infrastructure, transportation and local services across different institutional contexts. This comparative framework of examining the same instrument – a PPP – to acquire different goods and services in different places allows us to gain a comprehensive insight into the use of this policy tool. In this introductory article we frame the symposium by identifying a series of fundamental scholarly questions about the use of PPPs and highlight how the contributions to the symposium provide some answers to these questions. This short review of the contributions also sheds light on where gaps in the knowledge base on PPPs remain to be filled.

Fundamental questions in local public–private partnerships

Three fundamental questions frame the use of PPPs at the local level: what do PPPs at the local level look like; what gives rise to the use of PPPs at the local level; and what are the outcomes of PPPs at the local level? We briefly cover each of these questions below and report on how the symposium contributions fit into the extant literature on PPPs.

What do PPPs at the local level look like?

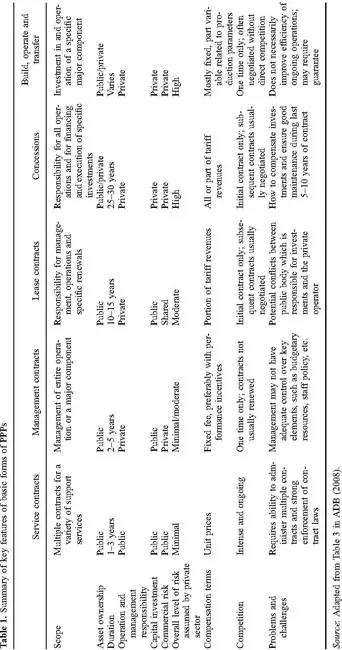

PPPs offer an alphabet soup of alternative forms (Osborne 2001). For new projects, PPPs typically involve some combination of design, build, finance, maintenance and operation (DBFMO) activities. These basic tasks can be exclusively assigned to either partner or can be shared. For existing services and facilities, PPPs take various contractual forms like a lease, concession or divestiture agreement. While these different forms are interesting in and of themselves, the underlying distribution of decision authority and risk are the defining features of PPPs. In this regard, Table 1 provides a useful typology of PPPs.

Sorting out which party has the right to make decisions about the project and who bears the risk, and concomitantly enjoys the rewards, has important implications for the likelihood of each side receiving a winning outcome. Two articles in the symposium tackle the question of the distribution of risk in the partnership. The contribution by Athias (2013) focuses attention on the allocation of demand risk in PPPs; that is, the risk for the provider that the demand for the service will fall short of initial expectations. If the level of use of the service is lower than projected, the provider faces the likelihood they will receive insufficient revenues to cover their investment costs. Athias develops a model that suggests that the transfer of demand risk to the private partner as opposed to the public authority motivates a greater response to customer needs. Furthermore, when customer preferences are likely to change over time, allocating demand risk to the private side provides better outcomes because responsiveness to consumer demands is higher. However, when the demand risk is retained by the public partner, the private partner is encouraged to reduce costs. The private partner may undertake cost reductions that reduce quality, thus reducing demand. However, while benefits from cost reduction are kept by the private partner, costs derived from reduced demand are born by the government. The author concludes that the optimal distribution of demand risk in the PPP is a function of the likelihood of customer preferences changing.

The second article, by Albalate, Bel and Geddes (2013), also examines risk, in this case the risk of cost recovery. This article examines the degree of private sector involvement in the water sector in the US. The authors classify a wide sample of PPPs in (1) management contracts, (2) design and build; (3) concession/BOT type contracts, and (4) asset sales. These contract types imply different degrees of private participation (from low to high), and also different levels of risk transfer to the private partner (from low to high as well). They use multivariate analysis to explain the degree of private involvement in the PPP and find that the higher the likelihood of the private partner recovering their costs, the greater the degree of private participation in the partnership. This suggests that local governments can increase the degree of private sector involvement and investment in PPPs where the commercial risk is relatively low. Another interesting finding in this article is that private participation is higher when salaries in the public sector are higher in relation to salaries in the private sector. Taken together these two articles emphasise the importance of looking beyond a simple categorisation of DBFMO activities to understand how the design of the PPP influences the likelihood of each party benefitting from the partnership.

Renegotiation is one of the key concerns in privatisation of public services as well as in PPPs, and increasing attention has been devoted to it since works by Guasch (2004) and Guasch et al. (2006, 2008) provided broad information and analytical understanding of the high frequency and speed of contract renegotiation. A third article in this symposium issue by Cruz and Marques (2013) highlights that many PPPs are subject to renegotiation. The initial distribution of DBFMO activities is often only the starting point for subsequent efforts to redistribute activities, decision authority and risk. When the partnership gives one party, say the private entity, exclusive decision authority over the project’s attributes, but places the cost responsibilities (and the financial risk) on the other party, in this case the local government, the likelihood of both sides coming out better off than when they entered the partnership is low. In this case, the arrangement appears to favour the private entity. Through an examination of a light rail contract, Cruz and Marques demonstrate how poor contract design at the outset can lead to opportunism by one or both parties. Cruz and Marques propose that more complete contract clauses (that is, clauses that provide greater clarity about the distribution of decision authority and risk) can potentially reduce the likelihood of opportunism and costly contract renegotiation.

What gives rise to the use of PPPs at the local level?

PPPs have been around for a long time, but their use in the last decade has increased. Much of this growth has been in the developing world, but there has also been increased use in the advanced industrialised world. The general explanation is that fiscally constrained governments enter these partnerships because they cannot afford to undertake the project on their own, and private entities join because a partner able to spread costs over a large pool of taxpayers is willing to shoulder risks that the private entity could not (or would not) take on its own (McQuaid 2000). This basic explanation provides a starting point, perhaps even a foundation, but other factors are likely at work, like the size of potential investment returns, the characteristics of the good or service to be produced and delivered, the degree to which the legal framework permits the use of different types of PPPs, and the political orientation of policy makers.

A trio of contributions to the symposium examines the relative influence of an array of factors on the use of PPPs. Simões, Carvalho and Marques (2013) examine the existence of economies of scale and scope in local public services. Both types of economies favour the use of different types of partnerships, with economies of scale favouring higher degrees of aggregation of service, thus favouring the using of PPPs. By means of partial frontier methods, they evaluate the presence of economies of scale and scope in the delivery of waste, water and wastewater treatment in Portugal. They find diseconomies of scope between waste and water (and wastewater) services and economies of scale only for the smallest municipalities.

Wassenaar, Groot and Gradus (2013) investigate the motivating factors for different local service delivery arrangements in the Netherlands. Common public choice, transaction and other institutional and pragmatic motives were investigated. Their qualitative analysis of interviews with local government decision-makers demonstrates that a long list of factors influence the use of different arrangements, including: efficiency and service stability pressures; service specific characteristics that give rise to transaction costs; the independence of external providers; the retirement decisions of municipal employees; the expertise of public employees relative to private sector firms; and the ideology of political decision-makers.

Based on the service delivery decisions of municipalities in the Aragonese region in Spain, Bel, Fageda and Mur (2013) find that size is also an important factor. While larger municipalities prefer to privatise the delivery of services, smaller communities often prefer to cooperate and pool their resources to deliver services, a public–public partnership, so to speak. Because cooperation and contracting to a private producer are not compatible in the area studied, small municipalities can also use cooperat...