- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dawn Over Oman

About this book

Oman is one of the most beautiful and popular countries in the Middle East, yet a few years ago it was one of the world's backwaters where visitors were discouraged. The turning point came with the takeover of power by Sultan Qaboos bin Said in 1970. This book, first published in 1979, takes the reader around the country, from the rugged Musandam peninsula in the north to the southern province of Dhofar. It builds a bridge between historical and modern Oman, describes the people and their landscapes, and the country's indigenous arts and crafts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART 1

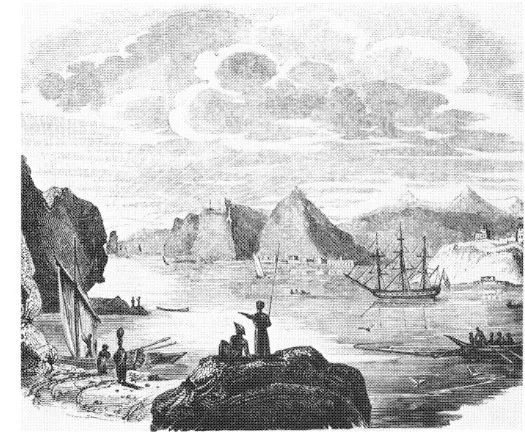

1. Old Matrah in the eighteenth century

1. The Long Night

To understand the Omani of today and his pride in his country and its development, it is necessary certainly to know something of the past history of Oman but not perhaps too much.

Much has been written about the old Oman – the warring tribesmen, the feuds, the backwardness of the country until as recently as 1970. It has been a journalist’s dream to write about these things and to romanticise them. Yet it is as well to remember that during much of this time Western countries, too, had their own sophisticated forms of barbarity; the slave trade after all was perpetrated by those who should have known better, and the worst atrocities ever committed in Oman were almost certainly those committed by the Portuguese.

All things considered the Omanis have come out of it all extremely well. They are among the friendliest people to be found anywhere today and the onrush of civilisation has neither spoiled them nor made them over-suspicious in spite of their monumental efforts to be good Arabs and toe the party line. But they are bored with hearing about the old days and would much rather talk about the recent tempestuous years after the butterfly emerged from the chrysalis and made its first ecstatic flight.

It is necessary to know something of the past, yes, but not to dwell on it hugely.

I remember vividly one night, it must have been in 1968, when I dined in Muscat for the first time. It was dark and we were ready to sit down to dinner when our host pulled back the curtain and beckoned me out onto the balcony of the British Bank of the Middle East, which is situated just outside the city walls and the Bab al Kabir, the main gate of the city. As we stepped out into the darkness a roar of gunfire sounded and we saw in the distance over the harbour a red flash outlining the battlements of Fort Mirani, black against the night sky.

Our host pointed to the gate. Slowly it was beginning to close – we could even hear the rusty hinges and the bolts being drawn. I was transported back to the Middle Ages, even more so later when we crept round the narrow streets with our oil lamps and were joined by Sayyid Abbas bin Feisal, uncle to the Sultan, and one of the few Omanis at that time who mixed freely with the foreigners.

Such was Muscat until 1970 where every night, three hours after sunset or dum dum (the Indian influence was very strong), the guns roared out from the Fort and the gate closed. It was ludicrous but enchanting.

And this was only the top of the iceberg, the part that was visible. Beneath the surface Muscat and the whole of Oman seethed and chafed under the restrictions imposed by their autocratic Sultan, Said bin Timur, a Sultan who lived away down in Salalah, 700

miles across the desert, and who had not even visited his capital for ten years. The whole country was an incredible anachronism.

All that is changed now. Oman’s ministers now attend summit conferences and take an increasing part not only in their own but in world affairs. It is a thriving nation with a healthy economy, respected by her neighbours and feared by her enemies, few though they may be. Schools and hospitals flourish, new ports, airports, hotels and housing estates blossom overnight and the Government and the Armed Forces have expanded out of all recognition from that year, so very little time ago.

To chart Oman’s progress on a graph would perhaps give the greatest impact, for the ups and downs of history, alternating with long periods of virtual stagnation, would provide very mild variations compared with the vast upswing of the last few years.

The known history of ancient Oman is somewhat sketchy. Certainly many fascinating references occur in various reports and sagas, chiefly from the time of the Portuguese occupation when the subject matter is bloodthirsty in the extreme. It was said at one stage in Oman’s chequered career that not a man or boy there died a natural death, and it was probably not far from the truth.

The barbarities practised by the Portuguese overlords in Oman make some of today’s war-crimes look like the play of children, but one should see in perspective the brutality practised against slaves who frequently had hands and feet and, more often, noses and ears, cut off for comparatively trivial offences: it was a barbaric area and they were barbaric times.

As to the country itself, many descriptions of Oman and its geography have been passed down to us by passing travellers or sailors who stayed a while and sailed away. As such, they are often suspect from a historical point of view, being highly exaggerated by men unused to lands other than their own and therefore prone to a great wonder.

The prehistory of Oman was virtually unknown until interest became aroused among amateur historians and archaeologists resident in the country with the formation of the Oman Historical Society in 1971. The Society was founded under the guidance of the newly formed Department of Information and Tourism and under the patronage of His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said in an endeavour to salvage as much as possible of the old Oman before it disappeared in the maelstrom of new building and reorganisation that was taking place, and before the new, brash, businesslike Oman lost for ever the atmosphere and surroundings that give it that infinite charm and attraction for local residents and foreigners alike.

Information began accumulating rapidly and from random notes by enthusiastic amateurs and occasional help from visiting professionals new profiles of old Oman began to emerge.

The oldest information, historically, came from an army colonel (now Brigadier Colin Maxwell) who had specialised in collecting flints while on duty down in South Dhofar. Some of these flints were found to rank among the finest Stone Age relics in the world, probably dating from the end of the period 5,000 – 3,000 BC. The flints were sophisticated for the time: leaf-shaped with hundreds of tiny facets formed by exerting great pressure on the flint whilst it was held rigid. From the high quality of the flint outcrop it was assumed that the interior of Dhofar was an important area in this later Stone Age. No remains were found relating to the Old Stone Age but work was hindered by the war. Now the war in Dhofar is over, much worthwhile material will no doubt come to light.

Over the last six years Oman has become a focal point for many archaeologists, geologists and anthropologists. Results have been published and reports correlated and an astonishing amount of material has been amassed in all fields.

Among the first of the experts to arrive in Oman with offical blessing was a Danish archaeological team, which visited the country for four months in 1973 at the invitation of the Government, who financed the expedition on the understanding that all finds belonged to Oman and that the team should publish the results of their work.

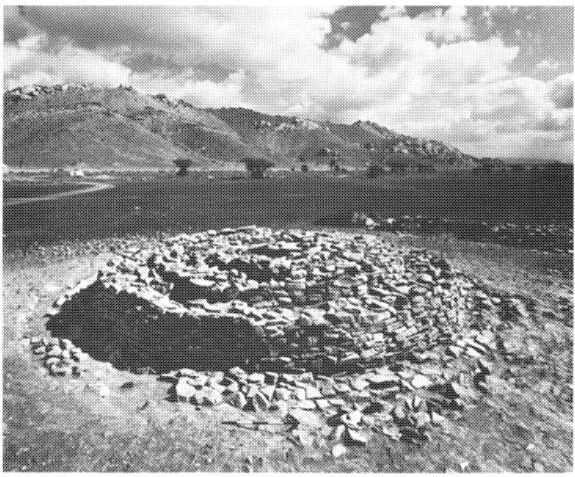

The team of five archaeologists from the Moesgaard Museum of Pre-History at Aarhus spent most of their time exploring an old trade route from Buraimi Oasis in the north running eastwards to Sohar on the Batinah coast of Oman and the fertile area around Ibri between the mountains of the interior and the desert. The principal interest for the archaeologists lay in the ‘grave-mounds’ which have puzzled travellers in Oman for many years. About a hundred of these graves were examined and, although they had been robbed of their contents, there were remains of fine painted pottery and incised stone vessels testifying to the sophistication of the civilisation of the time.

The grave-mounds themselves were beehive-shaped and made of impressive masonry. They were well planned and up to four metres (13 feet) high and ten metres (33 feet) across at the base. The pottery and stone vessels excavated from the graves showed definite connections with those in southern Persia in the fourth millennium BC and with the Jamdat Nasr period of Mesopotamia around 3,000 BC.

The groups of graves appeared to belong to the Umm An Nar culture, named after the island where it was first found by a previous archaeological team in Abu Dhabi, and could support the suggestion that Oman might once have been part of the legendary land of Magan mentioned in cuneiform tablets from about 2,000 BC as trading copper to Mesopotamia. The origin of Magan, or Makan as it is often called, has always been in doubt. Here then was the probability that it was located in Northern Oman and this probability was further supported the following year when substantial copper deposits were found in the area by a mineral research company. In Professor Kramer’s translation of tablets from the legendary island of Dilmun, now identified with Bahrain, occurs the blessing ‘May the land Magan bring you mighty copper …’. Diorite, an igneous rock consisting chiefly of feldspar and hornblende, was also a product of Magan.

2. Beehive-shaped grave-mounds near Ibri in Northern Oman, investigated by the Danish archaeological team in 1973

Since the first official Expedition in 1973 many other expeditions under British, Americans, French, Danes and Italians have visited Oman to explore archaeological sites, study architecture or report on mining and tribal law, water resources and human behaviour. Oman has been dragged, like it or not, under the microscope. Most of the findings have been reported in great detail in volumes I and II of the Journal of Oman Studies, published by the Ministry of Information and Culture, Sultanate of Oman, and, while most are interesting enough in their own right, their greatest value probably lies in providing a basis for more detailed future work.

One particular field, peculiar to Oman which proved of great interest to both amateurs and professionals alike is so-called ‘rock art’. Many travellers had noticed these usually crude drawings and writings on limestone faces in various parts of the country but, until the arrival of a young British anthropologist, Christopher Clarke, no serious work had been done on the subject.

Clarke spent a few months in 1973 drawing, photographing and mapping some of these drawings and much fascinating data came to light as a result. Only limestone faces were used, and the areas were generally in wadis used by regular travellers over the years, principally in the Wadi Uday between Ruwi and the Saih Hatat or Wadi Bani Kharus just above Awabi or in the Wadi Sahtan near Tabaqa. The areas probably corresponded to camping sites frequented by travellers from the coast to the interior centres of population.

The figures themselves were of particular interest and included not only human figures, generally of the ‘stick-man’ variety, but animals such as horses, camels, dogs, birds, bulls, ibex and even elephants. Men are represented standing on horses, carrying weapons, often naked or with a simple wraparound phallus sheath. These figures resembled figures on cylinder seals of the Akkaddian period (about 1700 BC). Some of these figures had obviously served as targets for sling shots and soft lead bullets but this firing probably came later – it seems unlikely that the drawings were made for this purpose.

Non-figurative designs are also common, some simple but others in complicated geometric patterns, while other limestone surfaces bear writing, the texts mainly Koranic. One inscription was found to be in Old South Arabian, the first ever example of pre-Islamic script to be found in Oman outside Dhofar.

The rock drawings and writings have not so far been dated and this dating will be difficult. Many are obviously modern, showing pictures of cars and trucks, while others are also modern but have been copied from the old. However, regarding the pictures in the context of their surroundings and other finds nearby may help to fix a date. Further work on this subject was done in the spring of 1973 by Christopher Clarke and Keith Preston. (See ‘An Introduction to the Anthropomorphic Content of Rock Art of the Jebel Akhdar’ by Keith Preston; Journal of Oman Studies, volume II.)

3. Typical rock art designs on the limestone face of a wadi in Central Oman

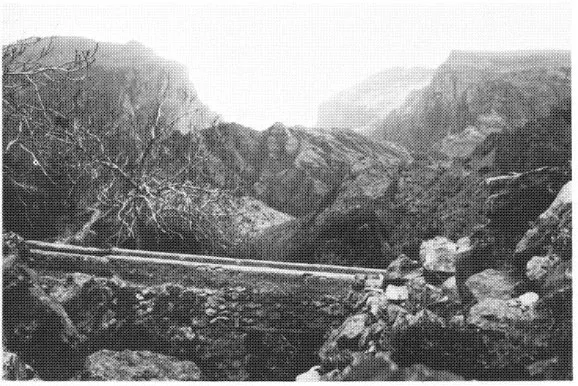

Another fascinating feature to the traveller in Oman is the preponderance of ‘falajs’ or mud-walled water channels, a form of irrigation introduced by the early Persian settlers which is so efficient that it is still in use today, some two thousand years later. A source of water is located, usually in the foothills of a mountainous area, and the water channelled from here underground to the area to be irrigated. Vertical shafts are dug along the path of the underground channel and connected by a tunnel. Where the watercourse crosses a wadi bed an inverted siphon is used, and on the surface the water is channelled to the various areas by the open ditches.

It is a complicated but eminently successful system and ensures running water throughout the driest summer. Due to this falaj system Oman, in spite of its extremely low rainfall, does not have a great water problem. Certainly at one time the country was fertile and agricultural and there seems little reason why much of it should not be so again.

Whole chapters could be devoted to ‘falaj law’ whereby villages or individuals are allotted certain times for obtaining water. The arguments relating to the distribution of such water supplies are among the chief subjects raised before the wali in the local majlis, the equivalent of a court of law.

The first conquest of Oman by the Persians, who were to play such a large part in the civilisation of the country, came in 536 BC during the reign of Cyrus the Great. The country at that time appears to have been known as Mazun or Mezoon and was called ‘a goodly land, a land abounding in fields and groves with pastures and unfailing springs’. It is interesting to note the similarity between the names Makan or Magan and Mazun and to read that in a battle on the plains near Nizwa a certain Malik defeated the Persian army of 30,000, his sons personally slaying one of the large Persian elephants. It is not so surprising after all to find elephants among the rock drawings.

Perhaps, indeed, some of the stranger animal designs can be explained by the following description of another battle against Persians this time in Syria – ‘In order to make up the deficiency under which the Muslim army laboured from want of elephants Qa’qa had recourse to a very ingenious device. He had some camels enveloped in fantastic housings and covered their heads with flowing vestments which gave them a weird and frightful appearance. On whichever side these artificial mammoths went the horses of the Persians shied and got out of control …’ which was hardly surprising!

4. Open falaj, or irrigation channel, with mud walls crossing a valley in the Jebel Akhdar in Central Oman

Oman was one of the earliest countries to embrace Islam and after the murder of Caliph Othman in AD 656 the ‘Kharijites’ broke away from the main body of Islam and turned against Ali, the fourth Caliph. The vast majority of the inhabitants of the interior of Oman today are Ibadhis belonging to this group, a very orthodox sect. They do not, however, regard themselves as a breakaway sect, rather as keepers of the true Moslem faith. Their leader is called an ‘Imam’ and is elected by a council of elders and he is expected to govern uprightly and uphold the true faith and the Shari’a or Moslem law.

The dominant feature of Oman has always been it...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- PART ONE

- PART TWO

- PART THREE

- PART FOUR

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dawn Over Oman by Pauline Searle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.