eBook - ePub

The Works of Charles Darwin: Vol 7: The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs

- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Works of Charles Darwin: Vol 7: The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs

About this book

The seventh volume in a 29-volume set which contain all Charles Darwin's published works. Darwin was one of the most influential figures of the 19th century. His work remains a central subject of study in the history of ideas, the history of science, zoology, botany, geology and evolution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Works of Charles Darwin: Vol 7: The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs by Paul H Barrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

ATOLLS OR LAGOON-ISLANDS

SECTION ONE, KEELING ATOLL

Corals on the outer margin – Zone of Nulliporae – Exterior reef – Islets – Coral-conglomerate – Lagoon – Calcareous sediment – Scari and Holuthuriae subsisting on corals – Changes in the condition of the reefs and islets – Probable subsidence of the atoll – Future state of the lagoon.

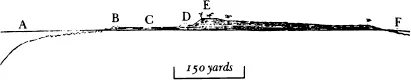

Keeling or Cocos atoll is situated in the Indian Ocean, in 12° 5′ S. and long. 90° 55′ E.: a reduced chart of it, from the survey of Captain FitzRoy and the officers of H.M.S. Beagle, is given in Plate I, fig. 10. The greatest width of this atoll is nine miles and a half. Its structure is in most respects characteristic of the class to which it belongs, with the exception of the shallowness of the lagoon. The accompanying woodcut (No. 3) represents a vertical section, supposed to be drawn at low water from the outer coast across one of the low islets (one being taken of average dimensions) to within the lagoon. The section is true to the scale in a horizontal line, but it could not be made so in a vertical one, as the average greatest height of the land is only between six and twelve feet above high-water / mark. I will describe the section, commencing with the outer margin. But I must first observe that the reef-building polypifers, not being tidal animals, require to be constantly submerged or washed by the breakers. I was assured by Mr Liesk, an intelligent resident on these islands, as well as by some chiefs at Tahiti (Otaheite), that an exposure to the rays of the sun for a very short time invariably causes their destruction.[1] Hence / it is possible only under the most favourable circumstances, afforded by an unusually low tide and smooth water, to reach the outer margin, where the coral is alive. I succeeded only twice in gaining this part, and found it almost entirely composed of a living Porites, which forms great irregularly rounded masses (like those of an Astraea, but larger) from four to eight feet broad, and little less in thickness. These mounds are separated from each other by narrow crooked channels, about six feet deep, most of which intersect the line of reef at right angles. On the furthest mound, which I was able to reach by the aid of a leaping-pole, and over which the sea broke with some violence, although the day was quite calm and the tide low, the polypifers in the uppermost cells were all dead, but between three and four inches lower down on its side they were living, and formed a projecting border round the upper and dead surface. The coral being thus checked in its upward growth, extends laterally, and hence most of the masses, especially those a little further inwards, had broad flat dead summits. On the other hand I could see, during the recoil of the breakers, that a few yards further seaward, the whole convex surface of the Porites was alive: so that the point where we were standing was almost on the exact upward and shoreward limit of existence of those corals which form the outer margin of the reef. We shall presently see that there are other organic productions, fitted to bear a somewhat longer exposure to the air and sun.

No. 3

A: Level of the sea at low water: where the letter A is placed the depth is 25 fathoms, and the distance rather more than 150 yards from the edge of the reef.

B: Outer edge of that flat part of the reef, which dries at low water: the edge either consists of a convex mound, as represented, or of rugged points, like those a little farther seaward, beneath the water.

C: A flat of coral-rock, covered at high water.

D: A low projecting ledge of brecciated coral-rock, washed by the waves at high water.

E: A slope of loose fragments, reached by the sea only during gales: the upper part, which is from six to twelve feet high, is clothed with vegetation. The surface of the islet gently slopes to the lagoon.

F: Level of the lagoon at low water.

Next, but much inferior in importance to the / Porites, is the Millepora complanata.1 It grows in thick vertical plates, intersecting each other at various angles, and forms an exceedingly strong honey-combed mass, which generally assumes a circular form, the marginal plates alone being alive. Between these plates and in the protected crevices on the reef, a multitude of branching zoophytes and other productions flourish, but the Porites and Millepora alone seem able to resist the fury of the breakers on its upper and outer edge; at the depth of a few fathoms other kinds of stony corals live. Mr Liesk, who was intimately acquainted with every part of this reef, and likewise with that of North Keeling atoll, assured me that these corals invariably compose the outer margin. The lagoon is inhabited by quite a distinct set of corals, generally brittle and thinly branched; but a Porites, apparently of the same species with that on the outside, is found there, although it does not seem to thrive, and certainly does not attain the thousandth part in bulk of the masses opposed to the breakers.

The wood-cut (No. 3) shows the form of the bottom outside the reef: the water deepens very gradually for a space of between one and two hundred yards wide, to a depth of 25 fathoms (A in section), beyond which the sides plunge into the unfathomable ocean at an angle of 45°.2 To the depth of ten or twelve / fathoms, the bottom is exceedingly rugged and seems formed of great masses of living coral, similar to those on the margin. The arming of the lead here invariably came up quite clean, but deeply indented, and chains and anchors which were lowered, in the hopes of tearing up the coral, were broken. Many small fragments, however, of Millepora alcicornis were brought up; and on the arming from an eight-fathom cast, there was a perfect impression of an Astraea, apparently alive. I examined the rolled fragments cast on the beach during gales, in order further to ascertain what corals grew outside the reef. The fragments consisted of many kinds, of which the Porites already mentioned and a Madrepora, apparently the M. corymbosa, were the most abundant. As I searched in vain in the hollows on the reef and in the lagoon, for a living specimen of this Madrepore, I conclude that it is confined to a zone outside, and beneath the surface, where it must be very abundant. Fragments of the Millepora alcicornis and of an Astraea were also numerous; the former is found, but not in proportionate numbers, in the hollows on the reef; but the Astraea I did not see living. Hence we may infer, that these are the kinds of coral which form the rugged sloping surface (represented in the wood-cut / by an uneven line) round and beneath the external margin. Between 12 and 20 fathoms the arming came up an equal number of times smoothed with sand, and indented with coral: an anchor and lead were lost at the respective depths of 13 and 16 fathoms. Out of twenty-five soundings taken at a greater depth than 20 fathoms, every one showed that the bottom was covered with sand; whereas at a less depth than 12 fathoms, every sounding showed that it was exceedingly rugged, and free from all extraneous particles. Two soundings were obtained at the depth of 360 fathoms, and several between 200 and 300 fathoms. The sand brought up from these depths consisted of finely triturated fragments of stony zoophytes, but not, as far as I could distinguish, of a particle of any lamelliform genus: fragments of shells were rare.

At a distance of 2,200 yards from the breakers, Captain FitzRoy found no bottom with a line 7,200 feet in length; hence the submarine slope of this coral formation is steeper than that of any volcanic cone. Off the mouth of the lagoon, and likewise off the northern point of the atoll, where the currents act violently, the inclination, owing to the accumulation of sediment, is less. As the arming of the lead from all the greater depths showed a smooth sandy bottom, I at first concluded that the whole consisted of a vast conical pile of calcareous sand, but the sudden increase of depth at some points, and the fact of the line having been cut, when between 500 and 600 fathoms were out, / indicates the probable existence of submarine cliffs of rock.

On the margin of the reef, close within the line where the upper surface of the Porites and of the Millepora is dead, three species of Nullipora flourish. One grows in thin sheets, like a lichen on old trees; the second in stony knobs, as thick as a man’s finger, radiating from a common centre; and the third, which is less common, in a moss-like reticulation of thin, but perfectly rigid branches.3 The three species occur either separately or mingled together; and they form by their successive growth a layer two or three feet in thickness, which in some cases is hard, but where formed of the lichen-like kind, readily yields an impression to the hammer: the surface is of a reddish colour. These Nulliporae, although able to exist above the limit of true corals, seem to require to be bathed during the greater part of each tide by breaking water, for they are not found in any abundance in the protected hollows on the back of the reef, where they might be immersed during either the whole or an equal proportional time of each tide. It is remarkable that organic productions of such extreme simplicity, for the Nulliporae undoubtedly belong to one of the lowest classes of the vegetable kingdom, should be limited to a zone so peculiarly circumstanced. / Hence the layer composed by their growth, merely fringes the reef for a space of about 20 yards in width, either under the form of separate mammillated projections, where the outer masses of coral are separate, or more commonly, where the corals are united into a solid margin, as a continuous smooth convex mound (B in wood-cut) like an artificial breakwater. Both the mound and mammillated projections stand about three feet higher than any other part of the reef, by which term I do not include the islets, formed by the accumulation of rolled fragments. We shall hereafter see that other coral reefs are protected by a similar thick growth of Nulliporae on the outer margin, the part most exposed to the breakers, and this must effectually aid in preserving it from being worn down.

The wood-cut (No. 3) represents a section across one of the islets on the reef, but if all that part which is above the level of C were removed, the section would be that of the reef, as it occurs where islets have not been formed. It is this reef which essentially forms the atoll. In Keeling atoll the ring encloses the lagoon on all sides except at the northern end, where there are two open spaces, through one of which ships can enter. The reef varies in width from 250 to 500 yards; its surface is level, or very slightly inclined towards the lagoon, and at high-tide the sea breaks entirely over it: the water at low tide thrown by the breakers on the reef, is carried by the many narrow and shoal gullies or channels on its surface, into the lagoon: a return stream lets out of the / lagoon through the main entrance. The most frequent coral in the hollows on the reef is Pocillopora verrucosa, which grows in short sinuous plates, or branches, and when alive is of a beautiful pale lake-red: a Madrepora, closely allied or identical with M. pocillifera, is also common. As soon as an islet is formed, and the waves are prevented from breaking entirely over the reef, the channels and hollows become filled up with fragments cemented together by calcareous matter; and the surface of the reef is converted into a hard smooth floor (C of wood-cut), like an artificial one of freestone. This flat surface varies in width from 100 to 200, or even 300 yards, and is strewed with a few large fragments of coral torn up during gales: it is uncovered only at low water. I could with difficulty, and only by the aid of a chisel procure chips of rock from its surface, and therefore could not ascertain how much of it is formed by the aggregation of detritus, and how much by the outward growth of mounds of corals, similar to those now living on the margin. Nothing can be more singular than the appearance at low tide of this ‘flat’ of naked stone, especially where it is externally bounded by the smooth convex mound of Nulliporae, appearing like a breakwater built to resist the waves, which are constantly throwing over it sheets of foaming water. The characteristic appearance of this ‘flat’ is shown in the foregoing wood-cut of Whitsunday Atoll.

The islets on the reef are first formed between 200 and 300 yards from its outer edge, through the accumulation / of a pile of fragments, thrown together by some unusually strong gale. Their ordinary width is under a quarter of a mile, and their length varies from a few yards to several miles. Those on the S.E. and windward side of the atoll, increase solely by the addition of fragments on their outer side; hence the loose blocks of coral, of which their surface is composed, as well as the shells mingled with them, almost exclusively consist of those kinds which live on the outer coast. The highest part of the islets (excepting hillocks of blown sand, some of which are 30 feet high), is close to the outer beach (E of the wood-cut) and averages from six to ten feet above ordinary high-water mark. From the outer beach the surface slopes gently to the shores of the lagoon; and this slope no doubt is due to the breakers, the further they have rolled over the reef, having had less power to throw up fragments. The little waves of the lagoon heap up sand and fragments of thinly-branched corals on the inner side of the islets on the leeward side of the atoll; and these islets are broader than those to windward, some being even 800 yards in width; but the land thus added is very low. The fragments beneath the surface are cemented into a solid mass, which is exposed as a ledge (D of the wood-cut), projecting some yards in front of the outer shore, and from two to four feet high. This ledge is just reached by the waves at ordinary high-water: it extends in front of all the islets, and everywhere has a water-worn and scooped appearance. The fragments of coral which are occasionally cast on / the ‘flat’ are during gales of unusual violence swept together on the beach, where the waves each day at high-water tend to remove and gradually wear them down; but the lower fragments are firmly cemented together by percolated calcareous matter, and they resist the daily tides longer than the loose upper fragments; and thus a projecting ledge is formed. The cemented mass is generally of a white colour, but in some few parts reddish from ferruginous matter: it is very hard and sonorous under the hammer: it is obscurely divided by seams, dipping at a small angle seaward: it consists of fragments of the corals which grow on the outer margin, some quite and others partially rounded, some small and others between two and three feet across; and of masses of previously formed conglomerate, torn up, rounded, and recemented: or it consists of a calcareous sandstone, entirely composed of rounded particles of shells, corals, the spines of echini, and other organic bodies generally almost blended together – rocks, of this latter kind, occur on many shores, where there are no coral-reefs. The structure of the coral in the conglomerate has generally been much obscured by the infiltration of spathose calcareous matter; and I collected an interesting series, beginning with fragments of unaltered coral, and ending with others, where it was impossible to discover with the naked eye any trace of organic structure. In some specimens I was unable, even with the aid of a lens, and by wetting them, to distinguish the boundaries of the altered coral and spathose limestone. Many even of the blocks of coral / lying loose on the beach, had their central parts altered and infiltrated.[2]

The lagoon alone remains to be described; it is much shallower than that of most atolls of considerable size. The southern part is almost filled up with banks of mud and fields of coral, both dead and alive; but there are considerable spaces, from three to four fathoms, and smaller basins from eight to ten fathoms deep. Probably about half its area consists of sediment, and half of coral-reefs. The corals composing these reefs have a very different aspect from those on the outside: they are numerous in kind, and most of them are thinly branched. Meandrina, however, lives in the lagoon, and many great rounded masses of this coral lie loose or almost loose on the bottom. The other most common species are three closely allied species of true Madrepora with thin branches; Seriatapora subulata; two species of Porites4 with cylindrical branches, one of which forms circular clumps, with only the exterior branches alive; and lastly, a coral something like an Explanaria, but with stars on both surfaces, growing in thin, brittle, stony, foliaceous / expansions, especially in the deeper basins of the lagoon. The reefs on which these corals grow are very ir...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction to Volume Seven

- Critical Introduction

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Table of Contents

- Description of the Plates

- Introduction

- Chapter I Atolls or lagoon islands

- Chapter II Barrier-reefs

- Chapter III Fringing or shore reefs

- Chapter IV On the growth of coral-reefs

- Chapter V Theory of the formation of the different classes of coral-reefs

- Chapter VI On the distribution of coral-reefs with reference to the theory of their formation

- Appendix I A detailed description of the Reefs and Islands in the coloured Map, Plate III

- Appendix II Summary of the principal contributions to the History of Coral Reefs since the year 1874

- Index