![]()

Part I

General principles of cognitive organization and change and implications for education

![]()

Chapter 1

Cognitive development in educational contexts

Implications of skill theory

Thomas R. Bidell and Kurt W. Fischer

As interest in cognitive developmental theory grew under the influence of Piaget’s work, the potential for a cognitive developmental approach to education seemed great. Behaviouristic approaches were largely retreating from classrooms in the face of a rising concern with children’s intellectual growth and autonomous activity in learning. Yet, despite the apparent promise, attempts to apply cognitive developmental theory have not met with widespread success, and there has remained a sizeable gap between developmental theory and educational practice. One major cause of this continuing gap has been the fundamentally context-neutral conceptions of cognitive abilities found in traditional theories of cognitive development.

The purpose of the present chapter is to advance an alternative view of cognitive abilities as context-embedded skills (Fischer 1980) and to discuss some of the implications of that viewpoint for educational research and practice. The argument begins with a critique of context-neutral conceptions of human abilities and a brief review of some of the educational problems associated with these conceptions. We then go on to define a new conception of cognitive abilities as context-embedded skills which moves beyond these problems, providing theoretical and methodological tools that can be used to understand the process of cognitive development as it takes place in different contexts and especially in educational settings.

CONTEXT-NEUTRAL CONCEPTIONS OF COGNITION

The conception of cognitive development that has influenced education the most has been the Piagetian theory of stage structure. Discussion of context-neutral conceptions of cognition will therefore concentrate mainly on stage structure, touching upon psychometric and competency conceptions only enough to indicate the ways that they share the context-neutral focus.

Piagetian stage structures

There has always been a tension in Piagetian theory between its constructivist framework and its structuralist stage model. Constructivism characterizes the acquisition of knowledge as a product of the individual’s creative self-organizing activity in particular environments. The structural stage model, on the other hand, depicts knowledge in terms of abstract universal structures independent of specific contexts. Indeed, the constructivist framework portrays an active human agent who knows the world by transforming it and actively adapting to its constraints. That view seems antithetical to the idea of abstract universal structures of knowledge virtually unaffected by vast individual differences in the sociocultural contexts and life histories of the people constructing the knowledge. If knowledge is in fact constructed in interaction with specific environments, then the nature of those environments should affect both the process of construction and the organization of the resulting knowledge.

For example, children solve arithmetic problems through a wide range of strategies constructed in a variety of specific contexts (Charbonneau and John-Steiner 1988; Saxe 1990). For young children, finger-counting strategies are prevalent, but in many schools contexts finger-counting is discouraged and children invent more subtle strategies including counting of marks on papers or counting without verbalizing. In some situations children are taught to make use of features on the numerals, like corners or curves, as ‘counters’. Each of these strategies involves some kind of organization of the thinking involved, and each situation calls for a different set of organized activities. One is hard pressed to understand the relation between the organization of each of these specific activities and the abstract concept of stage structure. Knowledge of an individual child’s stage of number conservation provides virtually no information about the organization of these specific skills or the ways in which a teacher might engage them in an educational interaction.

Yet, ironically, while educators have been attracted to Piagetian theory largely by its constructivist framework, it has been the structuralist stage theory that has received the most attention in educational research and applications (but, for constructivist approaches, see Duckworth 1989; Kamii 1985; Kamii and DeVries 1980). Piagetian constructivism has been attractive to educators because it emphasizes precisely those humanistic aspects of cognitive acquisition that behaviourism has denied – the creative activity of the human agent organizing herself and her environment (Bidell and Fischer 1992). Unfortunately, Piaget seldom drew a sharp distinction between his constructivist framework and his structuralist stage theory, and his descriptions of constructive mechanisms were couched in extremely general, even elusive terms (Piaget 1970). As a result, the emerging fields of cognitive development and developmental education adopted the stage theory as a testable, tangible point of departure for applying Piagetian theory to the classroom.

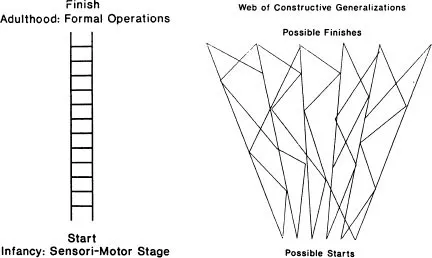

A corollary of this stage framework is a unilinear conception of the developmental pathway. Because each individual passes through the same sequence of universal stages, all individuals must share the same pathway of development and the same developmental outcome. Each person climbs essentially the same ladder from start to finish (Figure 1.1A). From this perspective it is difficult to understand how differing contexts and forms of social activity might influence the direction and outcome of development. Yet evidence from studies of cultural and gender differences suggests that developmental pathways and outcomes may differ considerably according to the systems of social expectations and cultural values within which individuals construct their knowledge (Gilligan and Attanucci 1988; Rogoff 1990; Saxe 1990; Whiting and Edwards 1988).

Figure 1.1 The developmental ladder (1A) and the developmental web metaphor (1B) for conceptualizing developmental pathways

Domain specificity and competence

Because of widespread recognition that the conception of universal stage structure does not account for the variability found in real people, the principle of domain specificity has been accepted by most contemporary cognitive developmental theorists (Carey 1985; Case 1985; Feldman 1980; Fischer 1980; Gardner 1983). According to these domain-specificity theories, knowledge is not organized in unitary structures that cut across all types of tasks and situations. Instead, knowledge is organized within specific domains defined by particular contents or tasks, such as arithmetic, spatial properties, social interactions, or music.

The recognition that knowledge does not have to be organized in single unitary structures is an important step away from context-neutral conceptions of cognition. Nevertheless, the principle of domain specificity alone is not sufficient for a context-embedded conception of cognition. Domain specificity theories often foster an organism/environment split by maintaining conceptions of cognitive abilities that focus mainly on the organism, the individual person free of contextual influences.

An extreme example of this split is the Chomskian conception of cognitive competence (Chomsky 1986). This framework portrays cognitive abilities as highly specific to particular domains such as language, spatial relations, or mathematics, and it locates these abilities almost entirely within the organisms, typically as innate endowments or modules (Fodor 1983; Spelke 1988). This strategy has the effect of conceptually separating the organism from the environment and reducing the role of the environment to little more than a trigger activating a specific form of a module.

Thus, despite the recognition of domain specificity, cognitive abilities continue to be portrayed in ways that separate context-specific performance from organismic cognitive structure. This conception therefore shares the problems of Piagetian stage structures with regard to education. With organism and environment radically separated, it is difficult to analyse how educational interventions in everyday performance might affect knowledge acquisition. Furthermore, even though different developmental pathways are prescribed for different domains, the pathways remain unilinear within those domains. The endpoint is determined biologically, and it is difficult to see how the person’s autonomous exchanges with the social environment might affect the course of this pre-established pathway to knowledge.

Psychometric intelligence

The most pervasive domain-specificity approach in education is probably the psychometric theory of intelligence, which is embodied in most educational tests. Psychometric conceptions do not make such a strong theoretical division between organism and environment as the Chomskian perspective, but they still focus the majority of attention on the role of the person rather than the environment. They thus perpetuate the organism/environment split by default, as it were.

Contemporary psychometric theories have partly addressed this problem by differentiating conceptions of cognition into differing domains or types of intelligence, such as verbal, spatial, musical intelligences (Demetriou this volume; Gardner 1983; Horn 1976; Sternberg 1985). Abilities are assessed separately for specific domains (classes of tasks or contents), still with the goal of characterizing the individual’s ability independent of the wealth of environmental factors that influence behaviour within that domain.

Individuals can thus have strengths and weaknesses in different domains, but the abilities continue to be placed primarily in the individual. The person is still cast as the main character, with the environment treated as something to be controlled or minimized. There are no specific provisions for understanding the role of context in the construction of knowledge or in the channelling of developmental pathways within each domain.

PROBLEMS OF CONTEXT-NEUTRAL THEORIES IN EDUCATION

Because context-neutral theories of cognitive development split the organization of knowledge from practice in context, they pose a fundamental contradiction for educators who wish to use them as tools for analysing specific educational processes. If the organization of thought and knowledge is primarily a property of the person (whether organized within or across domains) and therefore relatively impervious to contextual variation, then how can specific educational interventions affect it? Two particularly troublesome problems are an emphasis on an abstract concept of readiness and an inflexibility with regard to social and cultural diversity in development.

The readiness dilemma

Because of the split between organism and environment, context-neutral theories engender artificial divisions between development and learning and between cognitive structure and educational content. Cognitive structures are seen as the product of a developmental process that is somehow independent of learning. Development supplies general structures of knowledge, which have the educational role of readiness, preparing children’s minds for the experience of learning. Learning, on the other hand, has the role of filling up these preformed structures with educational content.

This artificial division of structure from content creates what might be called the readiness dilemma. Educators are forced to choose between the false alternatives of concentrating either on children’s cognitive structural development or on their learning. Either one must work to stimulate the development of cognitive structures to get children ready to learn (which is problematic since development is presumed to be mostly spontaneous) or one must wait patiently until the developmental process yields readiness on its own.

The first horn of this dilemma has led some educators to reduce the goals of education to those of development itself (Kohlberg and Mayer 1972). Then education requires methods of inducing structural development, such as teaching logic directly to children (Furth and Wachs 1974) or presenting materials just beyond a current stage in hopes of inducing children to stretch their cognitive structures upward (Turiel 1969). On the other hand, the second horn of the dilemma has led many proponents of stage theory to advocate a strategy of wait and pounce: observe children’s developmental progress and wait for just the right opportunity to introduce some stage-appropriate content.

Both of these alternatives disregard and devalue the everyday ongoing teacher-child and peer interactions that constitute the vast bulk of educational activities, and so both approaches have proven consistently futile. Because both alternatives ignore the everyday constructive activity through which children organize their knowledge, it is impossible for teachers to track the developmental process. Teachers are placed in the position of chasing after each child, attempting first to assess her stage of development and then trying to devise educational activities with just the right degree of cognitive challenge. The consistent experience of teachers in this position has been characterized best by Eleanor Duckworth (1979): ‘Either we’re too early and they can’t learn it or we’re too late and they know it already.’

Social and cultural diversity in development

A second problem with context-neutral theories for educational intervention lies in their implications about the pathways and outcomes of development. Context-neutral conceptions suggest a unilinear pathway of development (either within or across domains), abstracting a single sequence of acquisitions from the diversity of real children’s encounters with the environment. A major goal of education then becomes a matter of seeing all children through this unilinear sequence to a particular form of understanding at the end (Kohlberg and Mayer 1972).

Portraying educational objectives in terms of a single universal sequence and outcome poses two related problems for educating children from diverse social and cultural backgrounds. First, it restricts the flexibility of educational practice in adapting to differences in styles of thinking and learning. A single standard of development tends to rule out a priori the possibility of adapting developmentally based educational approaches to the needs of specific cultural, class, or gender groupings. Selecting a single developmental pathway – generally that which typifies white, middle-class, male development – as the standard of educational achievement risks alienating children who bring diverse backgrounds to the school culture.

Second, when the adoption of a single developmental standard is combined with the readiness perspective described above, it can lead to an inadvertently discriminatory laissez-faire approach to teaching in which children who do not belong to the dominant sociocultural tradition fail to receive training in academic skills presumed to develop in everyone (Delpit 1988). The readiness approach functions adequately for the majority of white middle-class children who, when left to their own devices, can be counted upon to develop, for example, mainstream literacy skills. On the other hand, children whose cultural contexts support different kinds of skills may be losing vital instructional time while teac...