- 334 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Employment, the Small Firm and the Labour Market

About this book

This volume provides a rigorous examination of key issues relating to employment in small businesses. These include an anlysis of the true extent of job crreation provided by small firms, the rleative quality of jobs in small firms, the growth of self-employment during the 1980s and the way in which the small firm interacts with its local labour markets. These issues are examined in an international context, wth comparative examples from the USA, the UK and Europe.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | Small firms and employment |

John Atkinson and David Storey |

INTRODUCTION

In 1978 the thirteenth Report from the Expenditure Committee People and Work, Prospects for Jobs and Training argued that ‘if each small business could take on one more employee, the unemployment problem would be solved’. Although it went on to recognize that this was an overly simplistic view of the operation of labour markets, it argued that ‘a whole range of legislation existed which prevented small businessmen from taking on additional personnel’. The clear inference was that if this legislation were removed, employment would grow and unemployment would fall.

Shortly after this, in 1979, the work of David Birch in the USA was extensively publicized by a newly elected UK Conservative administration. Birch (1979) purported to show that small firms, defined as those with less than twenty workers, provided a disproportionately high share of new jobs in the USA. Again, the inference drawn was that small firms were an appropriate focus of public policies for employment creation.

There can be little doubt that the emphasis upon the small firm in government policy, most notably through an attempt to create an ‘enterprise culture’ (Burrows 1991), drew its impetus from the perceived role of small firms in creating employment.1 There was a clear view that government could have a role to play in enabling small businesses to start up and expand. In particular, much of the mid-1980s saw an emphasis by the UK government on attempting to reduce the Burdens on Business (HMSO 1985) which its own legislation imposed, the effects of which were argued to fall disproportionately upon small firms. The view was widely held (Westrip 1982) that a relaxation of the legislative constraints upon small firms would enable them to take on the extra worker identified by the 1978 Expenditure Committee, and so reduce or eliminate unemployment.2

For much of the 1980s, researchers interested in the relationship between small firms and employment concentrated on four main issues. The first was to attempt to quantify the extent of the job creation provided by small firms. It focused upon the findings of Birch in the USA and the extent to which he was correct in drawing ‘legitimate’ inferences from the data. In the UK and in other European countries, efforts were made to replicate the Birch methodology to see whether similar results were obtained. This we may categorize as research on the total number of jobs, or job quantities. It focused upon the inferences which may be made from very large, yet incomplete, data bases; on the appropriateness of sampling techniques; the extent to which these results vary according to the state of the business cycle; and how employment change over time can be ‘decomposed’ into its component parts, such as births, deaths, and in situ change. Finally, it examines the extent to which employment change within the small firm sector can be influenced by public policy.

The second employment-related issue for researchers interested in small firms was the quality, as opposed to the quantity, of jobs in small firms. However, during the 1980s the emphasis given to this element of the research agenda was much less than that upon counting the number of jobs. Even so, a group of researchers continued to be interested in the nature of industrial relations within small firms, trade union membership, the availability of training for members of the work force, wage rates and non-wage benefits to the work force, implementation of employment legislation, job duration tenure, job satisfaction, etc. It has to be said that this type of research was clearly flying in the face of government initiatives to promote the small firm sector. As observed above, for much of the 1980s government saw its role as being to liberate the small firm sector from trade union membership, legislation involving workers’ safety, workers’ rights, etc. In so doing, it believed more jobs would be created and unemployment lowered. There was therefore little interest by public policy-makers in research on these questions, since policy was non-negotiable.

A third major topic of interest to small firm researchers concerned with employment issues was the spectacular growth in self-employment. In June 1979, 1.9 million people were classified as self-employed, with this constituting 7.5 per cent of the UK work force. By June 1990, 3.3 million people were classified as being self-employed, with this constituting 12.2 per cent of the work-force in employment (Campbell and Daly 1991).

By the late 1980s and early 1990s the research agenda on employment in small firms had begun to shift somewhat. More researchers began to consider how the small firm interacted with its local labour market. For much of the 1980s the implied assumption of policy had been that if constraints upon the small firms were lifted, this would lead to job creation and reduced unemployment. By the end of the period, however, researchers began to look at this issue from a fundamentally different perspective. They began to ask about the extent to which small firms were influenced by the labour market in which they operated, rather than assuming that small firms, as a group, had the ability to influence the character of that labour market. Researchers began to have an interest in how small firms acquired their labour, how they developed managers, how they were constrained by the labour market and, in turn, how this influenced the performance of the firm. Instead of examining the impact which small firms had upon the labour market, the reverse question also began to be addressed. Researchers began to recognize the complexities of the interaction between small firms and the labour market. This we regard as the fourth main issue.

In categorizing research developments in this very general manner, we do not intend to imply that researchers were unaware of the clear differences which exist between different ‘types’ of small firms. These differences of type have many dimensions. For instance, there are many different definitions of a small firm (Cross 1983; Dunne and Hughes 1990). The European Community definition of an SME, with less than 500 workers, is clearly different from the European Community definition of a craft firm which had less than ten employees, yet both are included within the interest group for Directorate General (DG23) of the European Community. Some leading researchers such as Curran et al. (1991) are reluctant to use any single definition of a small firm which applies across industry or service sectors. They prefer to use a ‘grounded definition’ in which those within the sector are asked for their definition of what constitutes ‘small’. Hence employment or financial criteria for a small firm in the petrochemicals or oils sector would be orders of magnitude larger than that for the small firm in retailing.

Researchers also became aware there were major differences amongst small firms’ performance according to the age of the firm (Evans 1987) and, to a lesser extent, according to its ownership (Varyam and Kraybill 1992). For example, the 1980s saw a growth in the number of business franchises on a major scale (Stanworth 1988), together with the development of community enterprises (Buchannan 1986; Jacobs 1986), and cooperatives (Cornforth 1983). The notion that the small firm sector was a homogeneous entity, suffering similar problems and experiencing similar opportunities, is fundamentally misguided.

The purpose of the essays in this volume is to provide an authoritative examination of issues relating to employment in small businesses. Each relates, at least partially, to the four themes which have been outlined above. Our purpose in this overview is to provide a context for these papers. To do this we provide a brief review of the research in the four key areas which we have already referred to above, and then link it to the new empirical material produced in the contributing essays.

HOW MANY JOBS?

Any discussion of this question has to begin with the seminal work by David Birch in the USA (Birch 1979). His work was interpreted as demonstrating that two-thirds of the increase in employment in the USA between 1969 and 1976 was in firms with less than twenty workers. As was pointed out in Storey and Johnson (1987), any work as influential as that of Birch will inevitably be the subject of intense scrutiny. Looking back over the last decade or so since Birch’s work first appeared, it is clear that, despite the major questions raised by the critics, it continues to be used by policy-makers as the seminal research which demonstrates the importance of small firms to job creation. Indeed, it seems that the more successful the critics were in undermining the methodology and the inferences, the greater was Birch’s credibility amongst influential groups of politicians.

The criticisms of Birch were first levelled by Armington and Odle (1982) who, using an identical data set, were unable to replicate the findings of Birch. This was essentially because the Dun & Bradstreet data used by Birch is incomplete in the sense that there are many missing establishments. Hence assumptions have to be made about establishments which are in the data base but which should not be, and those which are not in the data base but which should be. The nature of these assumptions fundamentally affects the numbers of jobs which can be attributed to small firms, primarily because coverage of the small firms sector is very much weaker than it is for larger firms. In more recent times Brown, Hamilton and Medoff (1990) have returned to the attack on Birch’s results:

We have seen that small employers do not create a strikingly high share of jobs in the economy, especially if we count only jobs that are not short-lived. Most jobs are generated by new firms, which happen to be small; existing small firms have relatively high chances of failing, and when this failure rate is taken into account they do not grow faster than larger firms. Indeed, in recent years they have shrunk faster than large firms. The share of employment accounted for by small firms has been remarkably constant.

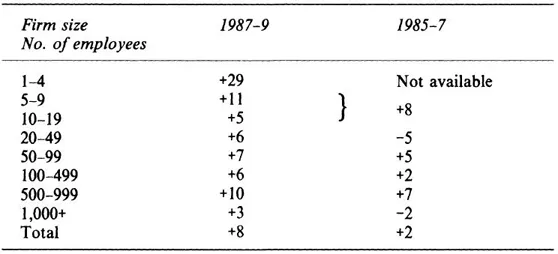

Table 1.1 Net job generation in the UK 1985–9

Sources: Gallagher, Daly and Thomason (1990); Daly, Campbell, Robson and Gallagher (1991).

Note: The table shows the change in employment (births minus deaths plus in situ change) for each size group expressed as a percentage of employment in that size group in the base year.

In the United Kingdom a similar debate has taken place. United Kingdom Dun & Bradstreet files were analysed (Gallagher and Stewart 1986) along similar lines to that which Birch employed in the USA. In a string of publications over a number of years, Gallagher and a number of other colleagues (Doyle and Gallagher 1987; Daly, Campbell, Robson and Gallagher 1991) have purported to show that small firms have been a major source of job creation in the UK. Table 1.1 illustrates these findings for the most recent time periods of 1985–9.

The results produced by Gallagher and his colleagues have been the subject of similar criticism to that levelled at Birch. In essence, the incomplete coverage of smaller firms in the UK Dun & Bradstreet data base means that the data on firms in the data base has to be scaled upwards to take into account these missing firms. The argument presented by Storey and Johnson (1986) is that the firms included by Dun & Bradstreet are not a random sample of firms in the UK. They are more likely to include firms which are growing, since Dun & Bradstreet is a credit-rating agency which is therefore more likely to include growing, and hence credit-seeking, firms. To scale up without adequately taking this into account leads to an over-estimation of employment created in small firms. Storey and Johnson (ibid.) also questioned the extent to which the data base had been adequately ‘cleaned’ to remove errors and mistakes.

The more recent studies, such as those by Daly, Campbell, Robson and Gallagher (1991), show that substantial work has been undertaken in ‘cleaning’ the data base. However, the scaling-up problem still seems to remain, and a genuine difference of opinion does exist between Gallagher and his critics on the importance of this issue.

In addition to the Storey and Johnson (1986) critique, criticisms of Dun & Bradstreet data base have also been levelled by Hart (1987). Hart argues that the Dun & Bradstreet data base looks to be fundamentally flawed because the death rates of firms appear to increase with firm size. He concludes: ‘The Dun & Bradstreet data are insufficiently reliable to draw any firm conclusions about the death rates of large and small firms’ (Hart ibid.).

Peter Johnson (1989) has also looked at employment change according to size, but only for UK manufacturing establishments. He shows that, whilst there has been an increase in the percentage of employment in establishments with under 200 workers, a substantial proportion of this is because of former large firms which have contracted in size. The increase in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- 1 Small firms and employment

- 2 Running to stand still: the small firm in the labour market

- 3 Employers' work-force construction policies in the small service sector enterprise

- 4 Labour market support and guidance for the small business

- 5 Labour intensive practices in the ethnic minority firm

- 6 Employment and labour process changes in manufacturing SMEs during the 1980s

- 7 Employment in small firms: are cooperatives different? Evidence from southern Europe

- 8 Generating enterprise and employment in disadvantaged urban areas

- 9 The characteristics of the self-employed: the supply of labour

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Employment, the Small Firm and the Labour Market by John Atkinson,David J. Storey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.