eBook - ePub

Cognitive Processes in Writing

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cognitive Processes in Writing

About this book

Originally published in 1980, this title began as a set of questions posed by faculty on the campus of Carnegie-Mellon University: What do we know about how people write? What do we need to know to help people write better? This resulted in an interdisciplinary symposium on "Cognitive Processes in Writing" and subsequently this book, which includes the papers from the symposium as well as further contributions from several of the attendees. It presents a good picture of what research had shown about how people write, of what people were trying to find out at the time and what needed to be done.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

THEORETICAL APPROACHES

1 | Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes |

Carnegie-Mellon University

Many have recognized that attention to process is potentially very important for the teaching of writing (Britton, Burgess, Martin, McLeod, & Rosen, 1975; Young, Becker, & Pike, 1970). Unfortunately, relatively few researchers have actually studied writing processes experimentally. Although noteworthy exceptions may be found in the work of Emig (1971), Zollner (1969), and Harding (1963), it is still true, as Britton et al. (1975) say, that “there has been very little systematic direct observation of fluent writers at work [p. 19].”

Cognitive psychologists have developed the technique of protocol analysis as a powerful tool for the identification of psychological processes (Newell & Simon, 1972). Although protocol analysis has most typically been used to identify processes in problem-solving tasks, as we will see, it can be used to identify processes in writing as well.

In this chapter:

1. We describe the technique of protocol analysis.1

2. We show how it can be used to identify writing processes.

3. We describe some early results in identifying writing processes that we obtained through its use.

WHAT IS A PROTOCOL?

A protocol is a description of the activities, ordered in time, which a subject engages in while performing a task.

A protocol, then, is a description, but not every description of a task performance is a protocol. Often we describe tasks mentioning only their outcomes or goals. We may say, for example, “My Great Dane, Spot, convinced me to give him his supper.” This description tells us that the dog did one or more things to get food, but it doesn’t say what these things were or in what order they occurred. That description, therefore, is not a protocol. The following description is a protocol, however.

Experimenter: | [seated at dinner table cutting into his steak] |

Spot: | [seated directly behind the experimenter, his chin resting on the experimenter’s shoulder. Spot watches intently as the steak is being cut.] |

Experimenter: | [skewers a large piece of steak with his fork] |

Spot: | [tail wags, stomach rumbles ominously] |

Experimenter: | [begins to raise fork to mouth] |

Spot: | [places paw on experimenter’s arm and looks intently into experimenter’s eyes] |

Experimenter: | “Spot!” |

Spot: | [removes paw, continues to watch intently] |

Spot: | [drools into experimenter’s shirt pocket] |

Experimenter: | [abandons own dinner and feeds dog] |

This is a protocol because it lists the activities that Spot engaged in and the order in which they occurred. In the same way, when we collect protocols of people solving problems, we are interested not just in the answers they give us, but, also and more important, in the sequence of things they do to get those answers. For example, they may draw diagrams, make computations, ask questions, and so forth, and they do those things in a particular order.

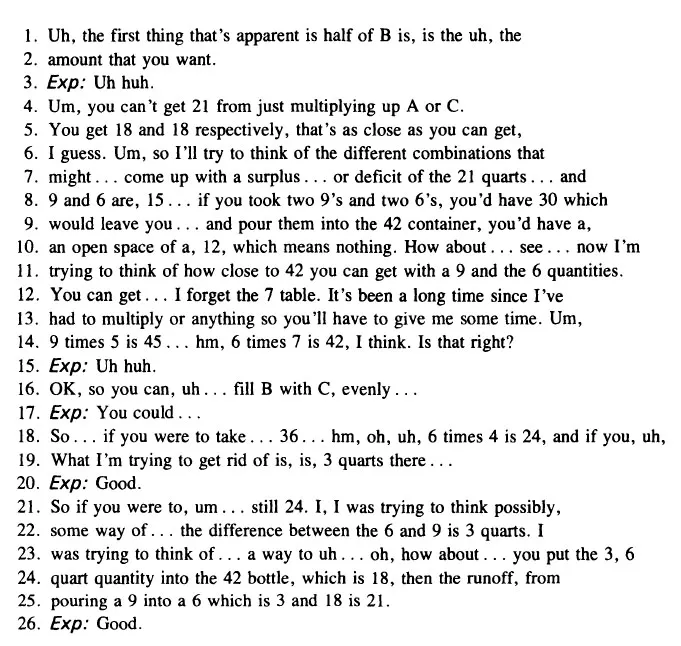

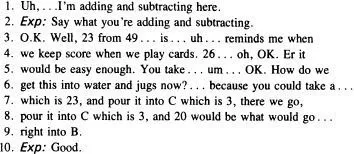

VERBAL PROTOCOLS

In a verbal, or “thinking aloud” protocol, subjects are asked to say aloud everything they think and everything that occurs to them while performing the task, no matter how trivial it may seem. Even with such explicit instructions, however, subjects may forget and fall silent—completely absorbed in the task. At such times the experimenter will say, “Remember, tell me everything you are thinking.” Figure 1.1 shows a typical thinking-aloud protocol for a subject solving a water jug problem.

FIG. 1.1. Protocol of a water jug problem.

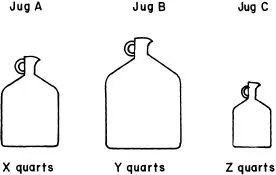

Water jug problems require the subject to measure out a specified quantity of water using three jugs, as shown in Fig. 1.2. None of the jugs has calibration marks. That is, there are no marks indicating a one quart level, a two quart level, etc. The subject is told only how much each jug will hold when it is full.

One typical water jug problem requires the subject to measure out 31 quarts when: jug A will hold 20 quarts; jug B, 59 quarts; and jug C, 4 quarts. The problem can be solved in four steps as follows:

1. Fill Jug B.

2. Fill Jug A from Jug B, leaving 39 quarts in B.

3. Fill Jug C from B, leaving 35 quarts in B.

4. Empty C and fill it again from B, leaving the desired quantity, 31 quarts, in B.

FIG. 1.2. Non-calibrated jugs used to solve the water jug problem.

It is helpful when you analyze a protocol to have done the task yourself beforehand. So, before beginning to analyze the protocol in Fig. 1.1, try to solve the following problem.

Measure 100 quarts given Jug A, holding 21 quarts; Jug B, holding 127 quarts; and Jug C, 3 quarts.

When you finish this problem, solve the problem in Fig. 1.1 if you have not already done so.

AN EXAMPLE OF PROTOCOL ANALYSIS

Now, let’s examine the protocol in Fig. 1.1 in detail and try to make some reasonable guesses about what the subject was doing.

In his first sentence, the subject mentions something that appears to be irrelevant to solving the problem. He mentions the fact that the desired amount (21 quarts) is just half the quantity contained in Jug B. Now, division is a very useful operation in many algebra problems. In this problem, if we could divide Jug B in half, the problem would be solved. But alas! There is no division operation in water jug problems. All we can do is add and subtract the quantities in Jugs A, B, and C. Why, then, does the subject notice that the desired quantity is half of B? The simplest answer seems to be that he is confusing water jug problems (perhaps because he isn’t thoroughly familiar with them) with the more general class of algebra problems. If this answer is correct, we would expect that the subject would stop noticing division relations as he gains more experience with water jug problems. In fact, that is what happened.

On line 3, the experimenter (Exp.) does just what the experimenter is supposed to do—that is, he is noncommittal. In general, the experimenter should answer only essential questions and remind the subject to keep talking.

From lines 4 and 5, we can guess that the subject has successively added 9’s to get 9, 18, 27… and 6’s to get 6, 12, 18, 24… and realized that neither sequence includes 21. From lines 6 through 10, we can see that the subject begins to consider combinations of 9’s and 6’s that may be added together to obtain interesting sums or that may be subtracted from the 42 quart container to obtain interesting differences. While considering sums, the subject fails to notice that the sum 6 + 6 + 9 solves the problem.

In lines 11 through 14, the subject tries to find out if 42 quarts can be obtained by adding 9’s and 6’s. The answer is “yes,” but it doesn’t help the subject to find a solution. It appears to be a “blind alley.” In this section, the subject indicates several times that he doesn’t feel confident about multiplication.

In lines 15 and 17, the experimenter provides the subject with a small amount of information by confirming his uneasy suspicion that 6 times 7 equals 42. On occasion, the experimenter must decide whether or not to provide information the subject requests. In this case, because the experimenter was really interested in water jug problems rather than in arithmetic, he decided to supply an arithmetic fact.

In lines 18 and 19, the subject realizes that if he had a way to subtract 3 quarts from 24 quarts, he could solve the problem. In line 20, the experimenter appears to slip by providing the subject with approval when he would better have remained silent. In line 21, the subject is still thinking of working from 24 quarts. In line 22, he discovers a way to add (rather than subtract) 3 quarts by pouring A into C and catching the overflow. In lines 23 and 24, he decides to work from 18 quarts rather than 24 quarts and then (on line 25) immediately solves the problem.

Now, let’s stand back from the details of the protocol to see if we can characterize the whole problem-solving process that the subject engaged in. Before reading further, review the discussion of the protocol and then try to characterize the problem-solving process yourself.

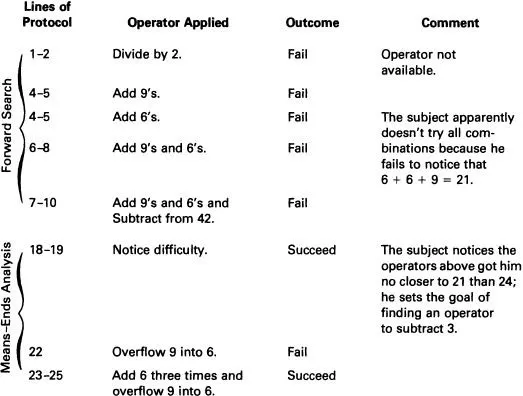

One way to characterize the problem-solving process is to describe it as a search for an operator or a combination of operators to solve the problem. (In this case, the operators are arithmetic procedures such as division and subtraction). In Fig. 1.3, where we have diagrammed this search process, we can see that search proceeds, generally, from simple to complex—that is, from single operators to complex combinations of operators.

Until line 18, the subject’s search for a solution could have been guided by the problem statement previously described. That is, by reading the problem statement, the subject could have decided that what was needed to solve the problem was some combination of algebraic operators. Until line 18, he could simply be trying one combination after another. We call this sort of search “forward search”; that is, it is search suggested by the problem statement alone. In lines 18 and 19, however, the subject formulates a goal on the basis of his difficulties in solving the problem. He notes that he hasn’t been able to get closer than 3 quarts to the answer and attempts to find an operator that will subtract 3 quarts. This goal depends not just on the problem statement but also on the subject’s experience in trying to solve the problem—that is, on his distance from the goal. It is a form of means-ends analysis in which the subject attempts to find a means to the end of reducing his distance from the goal.

FIG. 1.3. Analysis of water jug protocol.

The whole solution process then consists of:

1. An initial phase of forward search through an increasingly complex sequence of operators, followed by

2. A phase of means-ends analysis in which the subject succeeds in finding a solution.

In analyzing a protocol, we attempt to describe the psychological processes that a subject uses to perform a task. To do this, it is useful to be familiar both with the properties of the task and with the problem solver’s component psychological processes. In analyzing the foregoing water jug protocol, knowing that the task required algebraic operators and that human problem solvers often use processes of forward search and means-ends analysis helped us to recognize how the subject had organized these processes in his search for a solution. In the same way, when we analyze other protocols, knowledge of other tasks and of other psychological properties will be useful. This is not to say that we must already understand a performance before we can analyze it. It is just that when we do understand some things about the performance, we can use them very profitably to learn other things.

When we analyze the following water jug protocol, knowledge of the psychological phenomenon of set is very helpful. The problem used in this protocol can be solved in either of two ways. It can be solved by the procedure B-A-2C, or it can be solved by the simpler procedure A–C. Just before solving this problem, the subject worked a series of six problems, all of which required the procedure B–A–2C for solution. As a result, we would expect the subject to show a set to use the B–A–2C procedure. As lines 6 through 9 show, however, the subject actually solves the problem by the A–C procedure. Nevertheless, if we look back to 3 and 4, we see that the subject’s first problem-solving attempt was to subtract A from B, which suggests that he started to use the B–A–2C procedure even though he didn’t carry it through. Clearly, analyzing the protocol gives us evidence about the subject’s solution process that we can’t get just by looking at the subject’s answer.

PROTOCOL ANALYSIS — MORE GENERALLY CONSIDERED

As we have seen, protocol analysis can be used as an aid in understanding a wide variety of tasks from simple problem solving in apes to complex performances such as chess playing in humans. Typically though, protocols are incomplete. Many processes occur during the performance of a task that the subject can’t or doesn’t report. The psychologist’s task in analyzing a protocol is to take the incomplete record that the protocol provides together with his knowledge of the nature of the task and of human capabilities and to infer from these a model of the underlying psychological processes by which the subject performs the task.

Analyzing a protocol is like following the tracks of a porpoise, which occasionally reveals itself by breaking the surface of the sea. Its brief surfacings are like the glimpses that the protocol affords us of the underlying mental process. Between surfacings, the mental process, like the porpoise, runs deep and silent. Our task is to infer the course of the process from these brief traces.

FIG. 1.4. A water jug protocol.

The power of protocol analysis lies in the richness of its data. Even though protocols are typically incomplete, they provide us with much more information about processes by which tasks are performed than does simply exa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- I THEORETICAL APPROACHES

- II WRITING RESEARCH AND APPLICATION

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cognitive Processes in Writing by Lee W. Gregg, Erwin R. Steinberg, Lee W. Gregg,Erwin R. Steinberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.