![]()

1 Introduction

Synopsis

Customer satisfaction is the primary aim of marketing. In focusing on the future the enterprise ensures the best possible chance of attaining long-term stability and competitive standing. For the small enterprise faced with limited resources and the day-to-day pressures of business, marketing may sometimes seem an unnecessary luxury. However, as the enterprise moves along the growth cycle, the pressure for systematic planning and the associated information needs increases. The added cost of implementing the marketing function must be weighed against the possible consequences of living with a greater level of risk and uncertainty.

The nature of marketing

Marketing makes the basic assumption that customer satisfaction should be the primary aim of the business. Such satisfaction can only be achieved and sustained through the provision of competitive products or services, at competitive prices and by ensuring that communication with customers, directly or indirectly, is appropriate and effectively targeted. The marketing concept also acknowledges that in servicing the needs of the customer more effectively than competitors, the firm will optimize profitability over the longer term.

The longer-term (strategic) viewpoint provides the focal point for planning the future direction of the firm and the efficient harnessing of scarce resources towards achieving long-term goals. Although this focus will naturally enlarge the factor of uncertainty, it becomes increasingly important as the firm experiences the pains of growth.

Decisions on product development, pricing and distribution policies and promotional strategy (the marketing mix) will require support from appropriate and up-to-date information on the market(s) concerned, if the marketing planning function is to be effective. Not only is it a question of how to respond to the various market forces in the present, but also, to attempt to predict future change and to plan marketing responses accordingly.

Problems of generalization

While marketing principles have, in general, universal acceptance, marketing practice does not readily lend itself to standardization. Unlike, say, standard accounting routines which are widely accepted and practised, marketing is very much situation-specific in that it is dependent on several factors. For example, the nature of the markets served, the growth stage of the firm, the type of products or services offered, and the quality of management.

Therefore, it is difficult to generalize regarding the application of certain marketing theories and techniques. What may be appropriate for a manufacturing company in the way of new product development procedures, will probably be inappropriate for the retailing firm. Similarly, sophisticated marketing organization theories will have little meaning for the sole-ownership enterprise, but be highly applicable to the multi-market, multi-product firm.

In the final analysis, it is for the individual organization to judge what particular theories and techniques are most relevant to the situation, although the basic concept of marketing described previously applies in most cases.

The nature of the small enterprise

Definition

There seems to be little official agreement on what constitutes a ‘small business’. Various combinations of turnover, profit, and number of employees etc., have been suggested, but these classifications have proved somewhat arbitrary and thus any attempt to produce a rigid classification becomes meaningless. It seems however, that the stage of growth of the firm and the number of personnel involved in its management are probably better indicators. These factors have implications for responsibility of the individual business functions such as production, finance, sales etc., the extent to which these functions are formally (or informally) organized, and the availability of resources to support these.

For example, in the formation and early growth stages, it is common practice for the small enterprise to buy-in financial expertise and it is probably not uncommon for one person to be responsible for more than one function such as production and sales. As the burden of growth begins to tell, the divisions of responsibility become more apparent, and management will generally slot into the function which best serves their individual capability and/or interests, leaving gaps for others to fill.

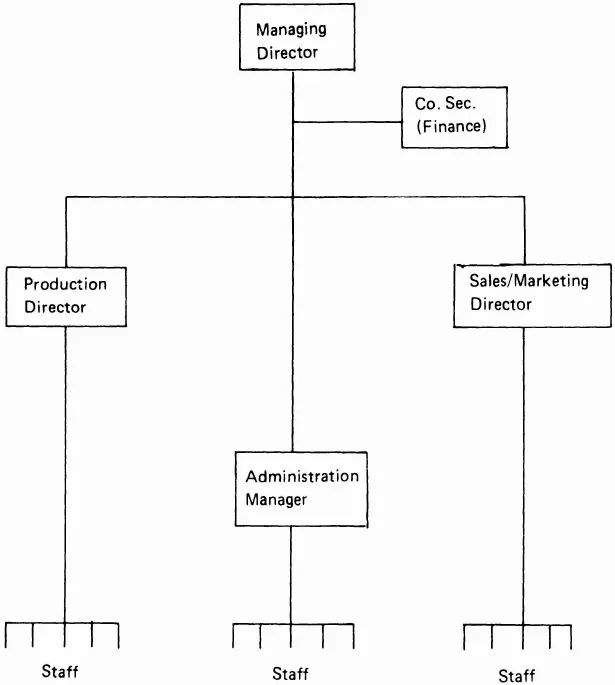

These early signs of formalization probably represent the transition from a small to a medium-sized enterprise, although again, it may be somewhat misleading to generalize. However, it is not unreasonable to assume that the organizational structure depicted in Figure 1.1 represents the upper limit beyond which the enterprise would probably not be considered ‘small’.

Figure 1.1 Functional organization

With further growth, through, for example, product and/or market diversification, changes in structure such as the formation of product groups or divisionalization are invariably accompanied by a relatively significant growth in number of employees and turnover.

Some facts and figures

Small enterprises are an integral and important part of the UK economy. In 1987 some 1.4 million small companies were registered for VAT in the UK and the average rate of new registrations was well over 100,000 per annum. However, past research has shown that the most critical period for the small enterprise is during the first thirty months of operation and that over a ten-year period, some 50 per cent of companies registering would have deregistered by the end of the period.

Research has also shown that unincorporated businesses such as sole proprietorships and partnerships, seem to have a better survival record in production, construction, transport, wholesale, motor trades, and other services. Companies, on the other hand, have done better in, agriculture, retailing, professional and financial services, and catering.

Marketing and the small enterprise

For the small enterprise hampered by regulatory constraints and coping with the day-to-day stresses of business, marketing theory and more so practice may at times, seem somewhat of an unnecessary luxury. It needs to be understood that if marketing is to be of any use, then time and scarce resources must be allocated to an activity which often may only show a return in the longer term. In the early stages of growth there are of course, seemingly more important activities which represent a considerable drain on resources such as the requirements of employees, purchasing, production, and financial reporting. Therefore, it is not hard to understand management’s over-preoccupation with these internal considerations and, indeed, this may well be the correct strategy depending on the particular situation.

As the firm moves along the growth cycle however, a much more externally orientated view is needed which takes account of changes in competition, customer demands, the economy, and technological developments among others. As the need for a more systematic approach to business development emerges, so the necessity to cope with greater uncertainty arises and the pressure for more information, skill at interpretation, and commitment to higher-risk decisions, collectively increase the burden on management.

There is of course the cost factor to consider in adopting a systematic planning approach and with the drain on resources faced by most small enterprises, marketing often tends to take a back seat. None the less, it is important to consider the possible cost of ignoring the issues and the subsequent longer-term problems that may arise.

Sometimes, management may only have a subjective or at best, a limited objective assessment of growth opportunity. Often, such recognition of an opportunity is based on an internally-generated idea or actual product, with little or no evidence of likely market response. Under these circumstances the risks associated with further development investment are considerably multiplied.

Information needs

For the various marketing decisions that face the small enterprise, more often than not, information on the market has to be gathered and interpreted. The sources of information may include customers, distributors, or published data on the industry and markets concerned. For many small enterprises specializing in fairly minor sectors of the market, broad statements on the market as a whole may be of little value; therefore much of the published information on markets will have its limitations. Reliable information is essential for effective market planning and the firm may have to resort to primary market research, that is, gathering relevant information which is not already available, be it on customers or competitors.

Decisions on products, pricing, promotion, and distribution (where appropriate) require at least a reasonable understanding of the market forces at play and this point is continuously stressed in the following chapters. Occasionally, the small enterprise will not only need information for its own use, but also to convince outside-interest groups of its credibility as a viable concern, as the following case study illustrates.

Precision Engineering Services

Simon Carter commented: ‘With my redundancy pay I set up a small engineering company mainly producing precision engineered components. As the orders increased I found I had to borrow to buy more machinery and the loan was secured on my house.

‘About three years later when I ran into cash-flow problems I approached the bank but they just didn’t want to know. The irony was that the business looked so promising, it just seemed unfair that even accepting the lack of security I wasn’t considered a safe bet.

‘As a last resort I contacted the local authority development corporation. Although I had to provide the usual forecasts and cash flows in support of the application I found it frustrating to answer pointed questions about the market, or my competitors, or my plans for the future. In truth, I didn’t have the answers at the time and of course I realize now I could hardly have expected any outsider to have shared my own faith in the business.

‘Although I wasn’t successful with the application I was advised to think about the issues and to re-apply at a later stage. As it happened, I had planned a weekend break in the Lake District, more for my wife’s sake really. She didn’t see much of me and I felt I needed to get away from the pressures of the business.

‘For the first time in the three years I had been in the business I began to collect my thoughts and to view things from the longer-term aspect. Surprisingly, my wife not only listened but she actually understood and seemed keen to be involved. In the relaxed atmosphere I was able to think morelobjectively and by the time we’d left the hotel I, or I should say we, had a much clearer idea of what was needed if the business was to survive.

‘Of course I had to get some professional guidance in the end, but I was much more confident and this seemed to rub off on customers. Eventually, I had a better idea of what, and who, I was up against, a much clearer view of the market, and, most important, a longer-term goal to aim for. I did get a loan after re-applying to the development corporation and looking back, I think the failure to get the money in the first instance was probably a godsend.’

Conclusion

From Simon Carter’s experiences we might assume that some of the problems facing small businesses result from a failure to project credibility on the one hand and caution – or over-caution – on the other. Clearly, conviction must be on both sides of the fence, whether dealing with customers, suppliers or potential sources of finance.

While in the early stages of development, the small enterprise may be relatively confident regarding decisions that come within the scope of marketing, successive growth plans, and growth itself, will increase the pressure both for more understanding of the market(s) and the effectiveness of existing and/or future marketing decisions. The latter may encompass new product development, pricing, distribution, and advertising and promotion decisions, all of which may require more information than is generally at hand. For example, price sensitivity of demand, advertising effectiveness, changing customer needs, and purchasing habits or the likely market response to a new product launch.

In contemporary business, sustaining success is largely to do with being competitive and this requires the enterprise to be aware of the behaviour of the market or markets, that it serves. While it may be tempting to reject the notion of gathering and interpreting information purely on economic grounds, the consequences could prove far more costly in the longer term. Certainly, it appears that marketing information and consultancy services are gradually coming within the pockets of smaller businesses and that such support is high on the list of government priorities:

The Enterprise Initiative announced last week by Lord Young, the Enterprise Secretary, promises a brave new world for Britain’s smaller companies. Little in the proposals is really new, but the government has provided much more money for a number of well-proven ideas, such as the subsidy of management consultancy.

The initiative attempts to overcome a particular hurdle facing any government attempt to get closer to small business. In the past the small-business owner has distrusted Whitehall as a source of finance or advice, convinced that civil servants do not understand his problems and that any help will be tied up in red tape.

The decision to create a network of offices around the country to provide counselling and, if required, referral to a professional management consultant, should overcome this reluctance to deal with government directly.

This network of offices – twenty-seven new ones are planned alongside the Department of Enterprise’s existing seven regional offices – will also add to the existing range of services available to small firms through the three hundred-plus Enterprise Agencies and the ten Small Firms Service Offices run by the Department of Employment.

Will the small businessman know where to go for advice? The answer is that the start-up or early-stage company in need of advice should approach its local Enterprise Agency or Small Firms Service office.

The Enterprise Agencies provide advice in an informal manner while the Small Firms offices give three sessions of free counselling followed by up to ten further sessions at £30 each.

The larger company which is already established but now wants to expand should apply to an enterprise counsellor in one of the Department of Trade and Industry offices. Many of the new ‘satellite offices’ will be based in Enterprise Agencies or chambers of commerce.

The new enterprise counsellors will give two days of free advice and assessment. If they think the problem justifies it they will recommend the use of professional management consultants. The government will meet half of the cost of advice for up to fifteen days though the subsidy rises to two-thirds in the assisted, and urban programme areas.

If t...