![]()

1

An overview: top down or bottom up?

The debate concerning world development1 has been a topical one for several decades. The persistent emphasis on Western biased models of development, men as the predominant social actors and production, provided the reader of the expansive literature with less than an integrative approach. The primary work in the seventies which moved the economic debate in the direction of a holistic argument encompassing men, women and children as social actors who resided in families and households in non-capitalist sectors was Ester Boserup’s influential book Women’s Role in Economic Development (1970). Boserup’s thesis was a radical departure from the assessment of economic indicators based on GNP made by modernisation theory. She argued that GNP does not incorporate non-marketable indicators which include the bulk of women’s informal sector, indirect waged, family and other unremunerated “invisible” contributions to the overall condition of a nation’s economy. She also emphasised the importance of recognising social historical patterns in different global regions which condition the particular type of wage labour pattern in any given region of the world. The issue of women therefore served to focus on the weak aspects of analysis within the development literature. This is an especially important focus at the present time for the discipline of development because debate has stagnated in general (see Booth 1985) and has not carried Boserup’s thesis forward. The inclusion of women, children and gender issues may be utilised to overcome this impasse (Taplin 1989, Sklair 1988, Dixon Mueller 1985). One of the major weaknesses in the bulk of development literature is that in relation to development it has concentrated either on the macro international facets of the economy or the national economy or the community in some cases of the microlevel. In addition, such analyses have consistently argued that social and economic change is directed from the external level of the world economic order. It is such unconnected analyses stressing one level of analysis or another, uniformly attributing change to external, world economic order and subsequently male dominated spheres that is causing an impasse in the discipline. This book suggests that what has been missing from such analyses is a macro-micro approach that takes account of multi-level linkages, both inter and intra. Such multi-level linkages we argue demonstrates that social, economic change may occur from the “bottom up” of the household/farnily level and not just from the “top down” world economic order level. This form of analysis is encapsulated in the proposed combination modes approach which is both a methodology and theory that serves to incorporate the necessary factor of women and children into the development equation as they are mainly concentrated within the bottom sphere of the family and/or household. Boserup’s book initiated a debate that has expanded traditional discussions of the processes of development to include such vital dimensions as gender, ethnicity and the reproduction of the family. The depth of the debate may be seen in the number of different schools of thought that have emerged in the past decade and a half. They include:

- The historical-materialist school of thought that produced the domestic labour debate which focussed on the theoretical question of whether housework in the broadest sense creates surplus value.

- The women in development (WID) school of thought which has modernisation leanings is located mainly in the United States and international organisations such as the ILO which views the incorporation of women into the capitalist marketplace as a primary focus for development planning.

- The world system/dependency school of thought that has very recently recognised the household as a feature of the world capitalist system focusses on the centrality of the Western capitalist (centre) world system showing how the household/wornen are affected by the world system rather than how the household/women may affect the world system.

- The cultural anthropological/feminist school of thought which redirected the debate towards the importance of cultural traditions socialisation and psychology in shaping the role of gender and ethnicity within the processes of development.

The expansive body of literature associated with these different schools of thought will be reviewed critically in this book after summarising the diverse constituent parts. A summation of the fifteen year long debates which have attempted to broaden the narrow foci of traditional development literature will seek to clarify gains made in theoretical understanding based on empirical evidence which maybe used to move forward the current impasse in the debate. In this particular book women will be used as a vehicle to show the vital necessity of including levels of analyses that focus primarily on gender, ethnicity, the family, household and reproduction for an integrated, holistic understanding of the processes of development and social change.

The critical review of the literature will emphasise both the strengths and weaknesses of the literature. Three primary weaknesses of the current literature will be isolated and addressed in Chapter One. The three major weaknesses that will be addressed in relation to the various schools of thought include:

- The lack of historical specificity, recognition of cultural diversity and the equal importance of many levels of analysis. These concepts are inter-related in that the history which comprises a unique accummulation of cultural experiences over a prolonged period of time occurs at multi-levels of society. The cultural history, the historically rooted ethnic identity of a nation or region shapes it in a manner that is specific to that nation or region. The household/family level of society is neglected in a number of ways in a good deal of development literature showing a lack of definition and more to the point its importance as a level of analysis. The insistence of many dependency or world system theorists that the societal level of the world economic order is the primary or sole unit of analysis that determines all other forms of historical movement neglects the equal importance of the household/family, ethnic grouping, nation and so forth as a unit of analysis. The capacity for the household level of society to initiate social change from the “bottom up” rather than from the “top down” of the world system level is not recognised by many development theorists. Analyses of women are therefore neglected inherently because female activity is often centred at the household/family level of society rather than at the level of the world economic order.

- The tendency to perceive particular groups of social actors such as women, peasants, the working classes or specific ethnic groups as passive victims of another group of social actors such as the capitalist classes, men or specific ethnic groups mainly because of a purported rigid, unchanging social structure that perceives one group of social actors as perpetually dominant to another subordinate group of social actors. Mass subordination that is rooted in rigid social structure implies passive victimisation which obscures the reality of the active resisting nature of “victims” lives. Many cultural anthropological/feminist and historical materialist analyses that emphasise the subordination of one group of social actors to another group of social actors explore the victimisation of the subordinated group rather than it’s resistance. Both the victimisation of the subordinate group and their resistance to the dominant group demands exploration as they are integrally linked phenomena. Analysis of the resistance of subordinated social groups may provide more vital information than details of victimisation because patterns of resistance illustrate the extent to which the particular social group has been effectively subordinated. The dominant group also demands a more rigourous investigation to determine how it is or if it is victimising the subordinate group. The reaction of the dominant group to the resistance of the subordinate group will demonstrate the intent of the former to victimise and the extent to which the latter group aids its own victimisation and presents itself as the victim. Too often the emphasis of theorists on the victimisation of a social group they deem subordinate amounts to a justification for the political ideology of the theorist.

Women in developing societies are often presented as helpless victims who passively accept their subordinate position to all men in society or an international capitalist class. The evidence shows the futility of portraying all women as universal victims of men or of an international capitalist class because in many societies they are not subordinate to males and are actually benefitting more for example, from multinational based opportunities than their male counterparts. The woman’s role of mother-in-law differs from that of daughter-in-law, for example.

- A methodological problem exists in a good deal of the development literature because of a lack of neutral categories of analysis free from ethnocentric bias and categorisation. Many theorists tend to analyse other developing societies in terms of their own, projecting ideas about their own society’s social organisation in a generalised manner to the society under observation. Phenomena unique to one country are universaiised and believed to be common to all nations. In the process of projection these theorists chauvinistically imply that their culture or attitudes are superior to all other social groups. Modernisation theory for example implies strongly in its terms of reference such as modern and traditional which correspond to Western and non-Western societies that modern is good and progressive while traditional culture is less than acceptable, even backwards. Feminists in turn are criticised for uni versaiising and projecting feminist concepts based on Western experience to women in developing societies.

Simply arguing as many neo-Marxist theorists do that social change inevitably emanates and is initiated from the “centre” (i.e. Western capitalist) region of the world is ethnocentric because the West is presumed to be the main influence on the lives of people throughout the world. A neutral set of categories that allows the analyst to explain and understand the constituent parts of the society under observation could be used to circumvent problems of ethnocentric bias.

Towards developing a theory that transcends many of the aforementioned weaknesses a presentation is made of the combination modes theory. This theory identifies three independent modes that incorporate their own dynamics and which may be used to define social change in world development in a neutral, historically specific manner. The three units of analysis of the combination modes approach include the organisation of work and related resources, the organisation of kinship and related resources and the organisation of ethnicity and related resources. It is suggested that none of these organisational modes of society exist in a “pure” form. The specific historical linkages between the organisation of work, kinship and ethnicity in any given society at any particular historical period produces a specific set of circumstances that is manifested at various levels of society and which affects men, women and children equally but differently depending on the level of society at which they are most actively involved with at the time of observation. The three conceptual units of analysis which are manifested at three levels of society include:

- The organisation of work and related resources (i.e. unearned accumulated wealth and the products of labour power) at the levels of the world economic order, nation state and community.

- The organisation of kinship and related resources (i.e. children, reproductive activities and human resources) at the levels of the family, household and lineage (clan).

- The organisation of ethnicity and related resources (i.e. religion, language, art and identity) at the levels of nationality, ethnic groups and tribe.2

Using the combination modes theory, the analyst may assess the nature of social change in terms of the particular combination of the three modes (including the various levels) found in a specific world region at a specific period of historical time. Social change may be initiated in any of the three modes at any particular level from either the “top down” (i.e. the world economic order within the organisation of work) or the “bottom up” (i.e. the family within the organisation of kinship). Social change may be initiated in this approach by one or more modes at one or more levels, (i.e. social change initiated by change in organisation of kinship may be manifested at the three levels of the family, household and lineage (clan). Each mode has its own internal dynamic and change occurs dialectically.

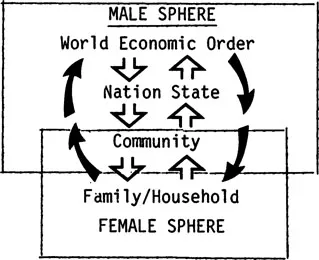

The case studies will analyse a number of societies using the combination modes theory as a basis for assessment. Women will be used as a vehicle for this assessment to demonstrate that the combination modes theory can accommodate the experience of women in an integrated manner which traditional development theory has failed to do. The case studies will focus on Malaysia, the Chinese Commune and the Israeli Kibbutz taking into account a variety of historical experiences, political regimes and economics; showing that diversity is so great in the arena of world development that social change may occur from the bottom up or top down in ways unique to the society under observation. Social change is so variable that change may be instigated by women in society, men in society, different ethnic groups or classes or a combination of two or more from all levels of analysis. Before proceeding to the review and criticism of the various approaches, beginning with the modernisation perspective, a diagram is presented below of the “Top-down - Bottom-up” paradigm of social change.

Top-down - Bottom-up Paradigm of Social Change

![]()

2

Review and critique of the literature and a theoretical proposal

The modernisation approach

Recent theories that have attempted to integrate the role of women into the development literature may be grouped into four broad categories including the modernisation, cultural-dualist, historical-materialist and dependency/sex/gender approaches. Modernisation theory has been one of the more widely known traditional analyses accepted by Western schools of thought which initially inspired criticism by Ester Boserup and subsequent authors.

The modernisation approach supports the idea that women have been in varying degrees subordinate to men; similar to structural-functionalism the formal structures of society that distribute power and authority are seen to determine the position of women in any given society. In what the modernisationists term a pre-modern or simple economy, the emphasis of this research resides with the degree of formal control that women exercise over resource distribution, decision making, services in society, patterns of childbearing and symbolic religious institutions (Freidl 1975). People in simple economies have fewer opportunities for self-advancement than they do in modern societies because of the dearth of occupational specialisation, technology, formal institutions and subsequent lower levels of productivity found in traditional societies. In modern or complex societies the degree of gender equality is measured by the position of women in jural, educational and work structures. Women in pre-modern societies are believed to be subject to patriarchal domination, oppressive childbearing and other family functions. Complex societies are seen to facilitate sexual equality with men, by providing new educational and occupational opportunities that allow access to the formal political-economic structures of society. Greater social mobility coupled with the higher levels of technology of the modern economy make commonplace conveniences such as household appliances and birth control devices that facilitate the participation of women in the formal sectors of society (i.e. Folbre, Ferguson 1981; Sullerot 1971; Freiden 1965). Social change is therefore predicated on upward social mobility into the formal institutions of society coupled by technological advances which move societies forward to modern or complex states of development, determining the position of women. Much of the literature dealing with women and development from a modernisationist perspective shares the belief that the lack of development in Third World nations is caused by the backwardness of traditional society and that the primary problem of Western (modern) development policies is that the benefits of these policies have mainly accrued to men. It is thought that women too require access to the modernised sectors of society. (Eisenstein 1981; Rogers 1981; Loutfi 1980; Zeidenstein and Abdullah 1979; Nelson 1979; Huston 1979; Whyte 1978; Dixon 1978; Epstein 1977; Clignet 1977; Kandiyotti 1977; Lahav 1977; Tinker 1976; Youssef 1974; Hammond and Jablow 1973; Sullerot 1971; Boserup 1970; Inkeles 1969; Kahl 1968; Wilensky 1968; Wood 1966; Weiner 1966; Collver and Langlois 1962).

Western ethnocentrism

The modernisation idea based on evolutionary structural-functionalist thought that all developing societies are in the process of becoming similar to the Western (modern) ideal is challenged for neglecting variation in different world cultures (i.e. Rothstein 1981; Geertz 1973; Goody 1973; Bendix 1970). The tendency of the modernisation approach towards Western ethnocentrism, and a lack of historical specificity is highlighted by its methodological emphasis on teleological progression towards a modern ideal. It is difficult to provide substantive quantitative or qualitative empirical evidence to document changes from simple to complex societies along a continuum while concentrating on the formal institutions of a society which are not uniform throughout all regions of the world. This makes it difficult to substantiate claims for example that male domination has been an integral part of traditional societies.

Many researchers (i.e. Clignet 1977; Kandiyotti 1977; Wilensky 1961) employing this approach place a number of different contemporaneous societies on a continuum scale to demonstrate progression towards complexity. Indicators utilised to assess complexity or higher levels of development tend to rely on generalised statistics such as GNP, mortality rates and educational achievement based on Western economic indices. Assessments of levels of development are predicated on Western models of capitalist industrialisation with socioeconomic indices compiled on the basis of those goods and services that enter a market. The concentration on the formal national market neglects the goods and services that are produced in the household/subsistence sector or other informal sectors often by women or national minorities.

Nash (1976) notes that increased self-sufficiency in agriculture is not viewed as progress by this approach...