![]()

Section IV

Material culture in action

![]()

15

The material culture of lineage in late Tudor and early Stuart England

In 1632 Sir Thomas Shirley commissioned what was, perhaps, the largest documentary text celebrating lineage in early modern England. It was a pedigree roll the size of a large advertising billboard (11 ft 9 in by 29 ft 2 in), consisting of a series of parchment strips sewn together. On it was recorded the genealogy of the Shirley family of Staunton Harold in Leicestershire, from their Anglo-Saxon ancestor, Sewale of Ettington, to the current head of the family, Sir Thomas’s elder brother, Sir Henry Shirley, Bart. At the top of the roll were pictures of knights, barons and earls bearing the escutcheons of noble families into which the Shirleys had married. At its foot was the Shirley coat of arms, with its 50 quarterings and family crest of a Saracen’s head. The body of the text contained the family tree and coloured drawings of the various sources which Sir Thomas had used for tracing his genealogy: deeds and documents, armorial glass from church windows, and funeral monuments and brasses1 (Figure 15.1).

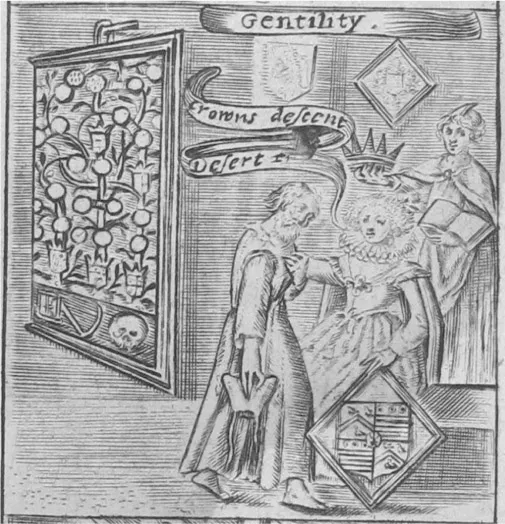

Pedigree rolls – often known as ‘tables’ or cards’ – had been introduced in the thirteenth century, mainly to depict the lineage of monarchs. But from the mid-fifteenth century, and especially in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, they became a familiar accompaniment to gentility, proclaiming and advertising the illustrious descent of the family being celebrated. Heralds and arms painters, such as the Chester deputy heralds Thomas and Jacob Chaloner and Randle Holme (I), regularly produced these, not only for the leading gentry but also those on the cusp of gentility.2 They became treasured artefacts, displayed on the walls of halls and parlours and passed down through the generations as ‘proof’ of a family’s illustrious ancestry and right to bear arms3 (Figure 15.2).

The earliest versions consisted of simple rectilinear pedigrees recording family members and coats of arms in circular boxes, but over time they evolved into something more elaborate, incorporating stylised portraits of family members – as in the renowned Hesketh genealogy of c.1594 or the brasses and monuments of the Shirley pedigree.4 In the latter case the sheer size and lavishness of the illustration considerably enhanced the impact. It was probably intended for display in the great hall of the family seat at Staunton Harold, which had been rebuilt on an extensive scale in the mid-sixteenth century.5 In this setting, it could take on the functions of a historical wall painting, setting out the Shirleys’ past achievements for others to learn from and emulate and depicting the particular glories of the lineage: the quality of its marriages, the enduring connection with places where ancestors lay buried and its sheer longevity. The roll is a classic representation of how a gentry family of the period wanted to imagine itself and wanted others to imagine it.

Figure 15.1 The foot of the Shirley Pedigree Roll of 1632 showing the family’s coat of arms, and, above it, the family tree and illustrations of funeral monuments. (Leicestershire and Rutland Record Office, 26D53, 2681. Reproduced by permission of the Archivist, the Leicestershire and Rutland Record Office.)

Figure 15.2 ‘The English Gentlewoman’ contemplating her descent following the demise of her husband, with a framed pedigree roll in the background: Richard Brathwait, The English Gentlewoman (1631), frontispiece. The Huntington Library, Rare Books: 60409.

The pedigree roll is just one example of a whole range of artefacts which were first produced in large numbers during Elizabeth’s reign and then became commonplace in gentry households and parish churches, all designed to celebrate lineage and ancestry. These included elaborately decorated grants and exemplifications of arms; furniture, wall hangings, family portraits, window glasses, fireplaces, plaster ceilings, book plates, embossed bindings, silver plate and earthenware with prominent heraldic decoration; funeral monuments and box pews in parish churches; and the various accoutrements which attended the increasingly popular heraldic funeral, such as pennants, banner rolls and replica armour.6 Cottage industries sprang up to cater for the demand, ranging from the workshops of tomb sculptors such as the Roileys and Hollemans at Burton on Trent and Garret Johnson and Richard Stevens at Southwark to the all-purpose manufactories of herald/arms painters, like Randle Holmes (I) and (II) of Chester.7 Taken together, these artefacts constituted a remarkable flowering of the visual and material culture associated with lineage. Most had been introduced and created in earlier centuries, but mainly for the benefit of royalty and the upper nobility. What is striking about the products of the Elizabethan and early Stuart period is their sheer ubiquity. They were everywhere – in houses, churches, schools, almshouses and civic buildings – and they were appropriated by all the different ranks amongst the gentry, from the long established to the newly risen and marginal.

This chapter is about this extraordinary and underappreciated phenomenon, which was at its height in England for just over a hundred years – from the 1560s through to the era of the Glorious Revolution. What survives is a small fraction of what was originally produced, but by contextualising what has remained and setting the objects alongside the textual evidence of how they were understood and interpreted by contemporaries it is possible to offer some explanations as to why this sudden flowering took place and how it helped to structure the contemporary environment and habits of thought and belief. These were artefacts which ranged from the everyday to the extraordinary – from the window glasses and decorated plate which must have been so familiar to everyday users as to pass virtually unremarked to the paraphernalia of the highly theatrical heraldic funeral or the motifs of the church monument when a visitor first encountered it. They could function in different ways for different audiences in different contexts. The large painted coat of arms, set in stone over the entrance to a manor house, had a very different resonance from the armorial windows, embossed tableware and heraldic fireplaces encountered in the more intimate space of a dining parlour. The former, through its scale and colour, was a public affirmation of rank and status that was accessible to all; the latter spoke very deliberately to the refined and heraldically educated sensibilities of one’s fellow gentlemen. Both, however, were drawing on a common language which, at an unconscious as well as a conscious level, did much to structure contemporary beliefs and assumptions.

Lineage

There is an influential narrative, exemplified in the work of Mervyn James, which argues that the attention and importance accorded to lineage was declining in the Elizabethan period. James describes a process of transition from what he calls a ‘lineage’ to a ‘civil’ society, from a society organised around the affinities of the great landed families to one based on association between the heads of patriarchal, nuclear families. Within this newly emerging society the ideal role for the gentleman changed from Christian knight to godly magistrate, and the ‘honour due to blood’ was downplayed in favour of the ‘civic’ virtues of wisdom, temperance and godliness.8 This idea of a transition from one notion of aristocratic honour to another has been criticised in more recent accounts, where the emphasis has been on ‘multi-vocality’ and ‘a medley of values’ co-existing and competing within contemporary honour culture.9 Felicity Heal and Clive Holmes, in particular, have demonstrated that whilst the political dominance of the great noble affinities may have been waning, belief in dynasticism and lineage was still extremely powerful. Sustaining one’s lineage was seen as providing purpose, substance, identity and a measure of security to landed families faced with unprecedented social mobility and the harsh demographic fact that in each generation around a quarter of them would die out in the male line. The reflections of the Isle of Wight gentleman Sir John Oglander, written down for the benefit of his surviving grandson, encapsulated the mixture of pride and anxiety which fuelled this preoccupation:

The de Oglanders are as ancient as any family in the Isle of Wight. They came in with the Conqueror out of Normandy and there have not wanted worthy knights of this family. But I confess they were of better esteem the first hundred years immediately after the Conquest then they have been since. Yet this is their comfort – that they have not only matched and given wives to most of the ancient families of the Island, but the name is still extant in a lineal descent from father to son…. We have kept this spot of ground this five hundred years from father to son, and I pray God thou beest not the last, nor see that scattered, which so many have taken care to gain for thee.10

What Christian Liddy describes as the ‘symbiotic connection’ between blood and land that characterised an ‘ancient’ gentry family, the satisfaction in an ancestry which could be traced back to the Norman Conquest and, above all, the sense that the continuity of the line was ultimately dependent on God’s providential blessing were all highlighted in Oglander’s musings; and his preoccupation with celebrating and perpetuating his lineage has been widely documented for other landed families.11 However, what has been less thoroughly documented is the sudden proliferation of interest in the cultural artefacts associated with lineage in Elizabeth’s reign.

The origins of this can be traced back to the sense of alarm amongst social commentators and royal officials in the mid-sixteenth century that if more was not done to fix in place existing social hierarchies the nobility and gentry would be deprived of the means to carry out their traditional tasks of governing and defending their country. This was a Europe-wide phenomenon, and it gave rise to similar concerns to tighten up definitions of nobility and find new ways of designating and proclaiming status.12 In England, much of the responsibility for this devolved to the heralds, who were given the task of drawing a clear line between gentleman and commoner. During the 1560s, under the auspices of the young reforming Earl Marshal, Thomas Howard, fourth duke of Norfolk, they expanded the scope of their activities, launching the first round of systematic, nation-wide, county visitations, recording gentry descents and coats of arms and publicly ‘disclaiming’ anyone who tried to usurp the title of a gentleman. Under Norfolk’s successor, the sixth earl of Shrewsbury, reform stalled, but the demands for the services of the heralds went on growing, and they developed a reputation for issuing coats of arms to whoever could afford them. The ...