![]()

I | ASSOCIATION LECTURE |

![]()

1 | The Case for Interactionism in Language Processing |

James L. McClelland

Carnegie-Mellon University

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

ABSTRACT

Interactive models of language processing assume that information flows both bottom-up and top-down, so that the representations formed at each level may be influenced by higher as well as lower levels. I describe a framework called the interactive activation framework that embeds this key assumption among others, including the assumption that influences from different sources are combined nonlinearly. This nonlinearity means that information that may be decisive under some circumstances may have little or no effect under other conditions. Two attempts to rule out an interactive account in favour of models in which individual components of the language processing system act autonomously are considered in the light of the interactive activation framework. In both cases, the facts are as expected from the principles of interactive activation. In general, existing facts do not rule out an interactive account, but they do not require one either. To demonstrate that more definitive tests of interaction are possible, I describe an experiment that demonstrates a new kind of influence of a higher-level factor (lexical membership) on a lower level of processing (phoneme identification). The experiment illustrates one reason why feedback from higher levels is computationally desirable; it allows lower levels to be tuned by contextual factors so that they can supply more accurate information to higher levels.

INTRODUCTION

When we process language—either in written or in spoken form—we construct representations of what we are processing at many different levels. This process is profoundly affected by contextual information. For example, in reading, we perceive letters better when they occur in words. We recognise words better when they occur in sentences. We interpret the meanings of words in accordance with the contexts in which they occur. We assign grammatical structures to sentences, based on the thematic constraints among the constituents of the sentences. Many authors—Huey (1968), Neisser (1967), and Rumelhart (1977), to name a few—have documented some or all of these points.

Clearly, this use of contextual information is based on what we know about our language and about the world we use language to tell each other about. How does this knowledge enter into language processing? How does it allow contextual factors to influence the course of processing?

In this paper, I will describe a set of theoretical principles about the nature of the mechanisms of language processing that provides one possible set of answers to these questions. These principles combine to form a framework which I will call the interactive activation framework. The paper has three main parts. In the first part, I will describe the principles and explore a central reason why they offer an appealing account of the role of knowledge in language processing. In the second part, I will consider two prominent lines of empirical investigation that have been offered as evidence against the view that particular parts of the processing system are influenced by multiple sources of information, as the interactive activation framework assumes. Finally, in the third part, I will discuss one way in which interactive processing might distinguish itself empirically from mechanisms that employ a one-way flow of information.

To summarise the main points of each part:

1. In the interactive activation framework, the knowledge that guides processing is stored in the connections between units on the same and adjacent levels. The processing units they connect may receive input from a number of different sources. This allows the knowledge that guides processing to be completely local, while at the same time allowing the results of processing at one level to influence processing at other levels, both above and below. Thus, the approach combines a desirable computational characteristic of an encapsulationist position (Fodor, 1983) while retaining the capacity to exploit the benefits of interactive processing.

2. Two sources of empirical evidence that have been taken as counting against interactionism do not stand up to scrutiny. The first case is the resolution of lexical ambiguity in context. Here I re-examine existing data and compare them with simulation results illustrating general characteristics of interactive activation mechanisms to show that the findings are completely consistent with an interactive position. The second case considered is the role of semantic constraints in the resolution of syntactic ambiguities. Here I review some recent data that demonstrate the importance of semantic factors in phenomena that had been taken as evidence of a syntactic processing strategy that is impervious to semantic influences. In both cases I will argue that the evidence is just what would be expected from an interactive activation account.

3. It is an important and challenging task to find experimental tests that can distinguish between an interactive system and one in which information flows only in one direction. Unidirectional and interactionist models can make identical predictions for a large number of experiments, as long as it is assumed that lower levels are free to pass on ambiguities they cannot resolve to higher levels. However, experimental tests can be constructed using higher-level influences to trigger effects assumed to be based on processing at lower levels. I will illustrate this method by describing a recent experiment that uses it to provide evidence of lexical effects on phonetic processing, and I will suggest that this method may also help us to examine higher-level influences on lower levels of processing in other cases.

THE INTERACTIVE ACTIVATION FRAMEWORK

The following principles characterise the interactive activation framework. These principles have emerged from work with the interactive activation model of visual word recognition (McClelland & Rumelhart, 1981; Rumelhart & McClelland, 1982), the TRACE model of speech perception (Elman & McClelland, 1986; McClelland & Elman, 1986), and the programmable blackboard model of reading (McClelland, 1985; 1986). The principles apply, I believe, to the processing of both spoken and written language, as well as to the processing of other kinds of perceptual inputs; however, all the examples I will use here are taken from language processing.

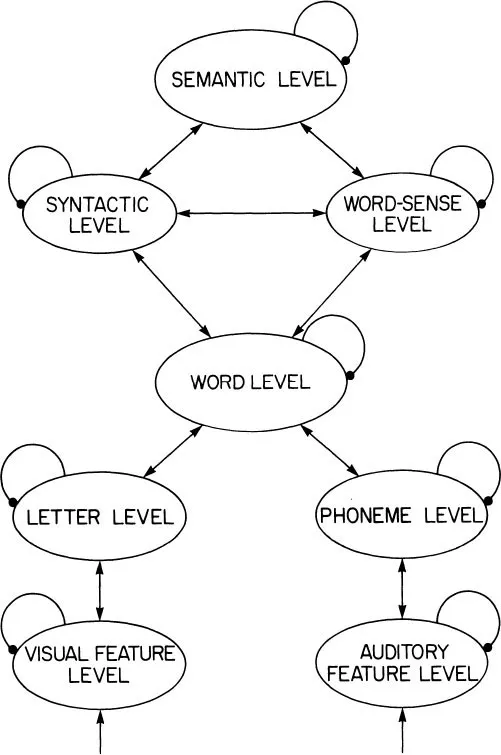

The Processing System is Organised Into Levels. This principle is shared by virtually all models of language processing. Exactly what the levels are, of course, is far from clear, but this is not our present concern. For present purposes, I will adopt an illustrative set of levels to provide a context in which to discuss the processing interactions that may be involved in reading a sentence. These levels are a visual feature level, a letter level, a word level, a syntactic level, a word-sense level, and a scenario level, on which the representation captures the nonlinguistic state or action described by the sentence being processed. Higher levels are, of course, required for longer passages of text, but the set of levels will provide a sufficient basis for the phenomena we will consider here. For processing speech, we also need a phonetic level and an auditory feature level to provide input to the phonological level.

The Representation Constructed at Each Level is a Pattern of Activation Over an Ensemble of Simple Processing Units. This assumption is central to the entire interactive activation approach, and strongly differentiates it from other approaches. In this approach, representations are active—they can influence, and be influenced by, representations at other levels of processing. In this paper, I will adopt the formal convenience of assuming that individual processing units stand for individual conceptual objects such as letters, words, phonemes, or syntactic attachments. Thus, a representation of a spoken word at the phonetic level is a pattern of activation over units that stand for phonemes; these units are role-specific, so that the pattern of activation of “cat” is different from the pattern of activation of “tac.”

Activation Occurs Through Processing Interactions that are Bi-directional, Both Within Levels and Between Levels. A basic assumption of the framework is that processing interactions are always reciprocal; it is this bidirectional characteristic that makes the system interactive. Bi-directional excitatory interactions between levels allow mutual simultaneous constraint among adjacent levels, and bi-directional inhibitory interactions within a level allow for competition among mutually incompatible interpretations of a portion of an input. The between-level excitatory interactions are captured in these models in two-way excitatory connections between mutually compatible processing units; thus the unit for word-inital /t/ has an excitatory connection to the unit for the word /tac/, and receives an excitatory connection from the unit for the word /tac/.

Between-level Processing Interactions Occur Between Adjacent Levels Only. This assumption is actually rather a vague one, since adjacency itself is a matter of assumption. I mention it because it restricts the direct processing interactions to a reasonably small and manageable set, rather than allowing everything to influence everything else directly. One possible set of interactions between levels is sketched in Fig. 1.1. Note that even though some pairs of levels are not directly connected, each level can influence each other level indirectly, via indirect connections.

Between-level Interactions are Excitatory Only; Within-level Interactions are Competitive. A feature of the interactive activation framework that has gradually emerged over the years is the idea that between-level interactions should be excitatory only, so that a pattern of activation on one level will tend to excite compatible patterns at adjacent levels, but will not directly inhibit incompatible patterns. The inhibition of incompatible patterns is assumed to occur via competition among alternative patterns of activation on the same level. This idea is characteristic of assumptions made by Grossberg (1976 and elsewhere), and its utility has become clearer in later versions of interactive activation models (McClelland & Elman, 1986; McClelland, 1985). The principal reason for this assumption is that it allows possible alternative representations to accumulate support from a number of sources, then to compete with other alternative possibilities so that the one with the most support can dominate all the others. This allows the network to implement a “best match” strategy of choosing representations; for example, a sequence of phonemes that does not exactly match any particular word will nevertheless activate the closet word. Thus “parageet” for example can result in the recognition of the word “parakeet,” even though it does not match parakeet exactly.

FIG. 1.1. A set of possible processing levels and connections among these levels. In an interactive activation model, each level would consist of a large number of simple processing units. No claim is made that this is exactly the right set of levels; this set is given for illustrative purposes only. Bi-directional, excitatory connections are represented by double-headed arrows between neighbouring levels. Inhibitory within-level connections are represented by the lines ending in dots that loop back onto each level.

Activations and Connections are Continuously Graded. The activation of a representation is a matter of degree, as is the strength of the influence one representation exerts on another. Degree of activation of a unit reflects the strength of the hypothesis that the representational object the unit stands for is present; the strengths of the connections between units reflect the strengths of the contingencies that hold between the representational objects.

The Activation Process is Nonlinear. Each processing unit in an interactive activation network performs a very simple computation. It adds up all of the weighted excitatory influences it receives from other units and subtracts from these the weighted inhibitory influences that it receives from competing units. Then, it updates its activation to reflect this combined (what I will call net) input. The activation of the unit is monotonically, but not linearly, related to this sum; at high levels of excitatory input, activation levels off at a maximum value, and with strong inhibitory input, it levels off at a minimum value. Because of these nonlinearities, and because of the competitive interactions among units, inputs that are sometimes crucial for determining the outcome of processing may have little or no effect at other times.1 The specific details of the nonlinear activation assumptions that I have used are based on, though not identical with, those used by Grossberg (e.g., Grossberg, 1978).

Activation Builds Up and Decays Over Time. It is assumed that processing interactions occur continually, but that the activation process is gradual and incremental, so that it takes time for activation to propagate through the system. New inputs begin to have their effects immediately, but these effects build up over time and then gradually decay away as processing continues.

These assumptions are now being applied in the construction of models of higher-level aspects of language processing, such as the assignment of constituents of sentences to semantic roles and disambiguation of word meaning in context (Cottrell, 1985; Waltz & Pollack, 1985; Kawamoto, Note 4; McClelland & Kawamoto, 1986). At higher levels of processing, I and other researchers have tended to build models that make explicit use of distributed representation, in which a conceptual object is represented by a pattern of activation, rather than a single unit (Hinton, McClelland & Rumelhart, 1986). However, even here it is convenient to speak of whole patterns of activation as though they were separate information-processing constructs, that interact with each other via excitatory and inhibitory contingencies. Indeed the distributed representation can be seen as an implementation of the more abstract, functional descript...