![]()

1

Reimagining Healthy Sexuality

“All things are subject to interpretation. Whichever interpretation prevails at a given time is a function of power and not truth.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, 1967

The concept of healthy sexuality has always been culturally defined by groups and individuals with the strongest overarching social influence. The lay public construct notions of healthy sexuality by sociocultural and financial influences. Moviegoers of all ages are bombarded by common storylines enacted by idolized actresses like Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman, or Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. Professional groups have also used marketing strategies to leverage panic and anxiety as motivating forces to get urgent treatment for unfounded ‘disorders’ like sex addiction. This chapter will highlight the historical underpinnings leading to social and professional concepts of healthy sexuality.

Pathologizing Sexuality

Richard von Krafft-Ebbing was a German psychiatrist who advocated a medical model of classification for alternative sexualities in his book Psychopathia Sexualis: Eine Klinisch-Forensische Studie (Sexual Psychopathy: A Clinical-Forensic Study), published in 1886. He cited case histories primarily concerning non-consensual sexual violence, which have no resemblance to what is now referred to as consensual sadomasochism or SM. Krafft-Ebbing was Sigmund Freud’s inspiration for developing a system of classification of pathology, of which Freud said, “sadomasochism was the most perverse” (Freud & Strachey, 1975). The ambitious Freud knew that by setting up his pathology classification, his theories would get co-opted into legal fields.

Freud’s legacy of pathologizing non-normative sexualities continues to this day. Until recently, research has been biased in that hypothetical foundations seek pathology and are non-ethnographically and nonempirically based. Freud’s misinformed classifications, as they pertain to modern-day BDSM, live on in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Over time, these definitions have become central to informing legal opinions and attitudes that lead to social, political, and cultural discrimination and persecution. In the clinical setting, this dynamic results in misdiagnosis due to demonizing what is unknown, feared, and misunderstood.

Until recently, homosexuality was an example of this form of institutionalized sociocultural pathological construction. In 1973, as a result of community organization and political activism, the gay community successfully had the classification of homosexuality removed from the DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). This led to de-pathologizing and decriminalization of homosexuality and the cascade of dramatic social shifts we still experience in today’s postmodern cultural and political discourse. This change also initiated an ongoing, large-scale process of acceptance of homosexuality as a legitimate expression of sexuality, and is now considered a cultural identity as well as a sexual orientation (Bayer, 1987; Drescher & Merlino, 2007). However, the other paraphilias continue to remain in DSM-5, largely without any unbiased clinically scientific evidence to support these expressions being pathological.

Healthy Sexuality Defined

If healthy sexuality is defined by those with the most influential voice in society, then who are they and how are they defining healthy sexuality in the current postmodern technological age? Healthy sexuality is changing as social and cultural awareness becomes open to new ideas. This prolific exposure occurs through the arts, media, and, in particular, the Internet. As a result, hidden and marginalized members of the BDSM communities are increasingly becoming more public. These social changes are preceding research and affecting the practice of psychotherapy – in particular, understanding definitions of healthy sexuality pertaining to emerging alternative sexualities.

Currently, there are no comprehensive and clear definitions of healthy sexuality that encompass emerging sexualities, particularly when addressing clients who identify with the BDSM lifestyle. The closest applicable definition was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in conjunction with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in 2006 and then partially updated in 2010.

- Sexual health: “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.” (World Health Organization, 2006)

- Sexuality: “a central aspect of being human throughout life encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. Sexuality is experienced and expressed in thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles and relationships. While sexuality can include all of these dimensions, not all of them are always experienced or expressed. Sexuality is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, legal, historical, religious and spiritual factors.” (World Health Organization, 2006)

It is essential to point out – and very obviously clear – that these definitions are largely addressing body integrity, safety, eroticism, gender, sexual orientation, emotional attachment, and reproduction from a public health perspective, in relation to broad cultures and specific scenarios around the world.

Various authors have contrasted sexual health with sexual well-being. Sexual well-being is constructed by an individual’s subjective assessment of their psychological well-being, which utilizes either a balance between positive and negative feelings pertaining to their sexual life or a favorable comparative assessment of their current sexual life with their ideal sexual life (Byers & Rehmann, 2014). Therefore, sexual health differs from sexual well-being in that the former is a broader concept. The later involves a subjective assessment of various aspects of the person’s sexual relationship and functioning, satisfaction with their responsiveness, frequency of activity, and sexual repertoire.

Figure 1.1 WHO definition of healthy sexuality.

![]()

2

There Are More Than Fifty Shades of BDSM

“One can say that S&M is the eroticisation of power, the eroticisation of strategic relations … the S&M game is very interesting because it is a strategic relation, because it is always fluid.”

– Michel Foucault (in an interview given to the Advocate [Gallagher & Wilson, 1984])

BDSM is an emerging phenomenon in mainstream society and, according to ethnographic research, is significantly misrepresented in the media (Ortmann & Sprott, 2013; Taylor & Ussher, 2001). The publication of E. L. James’s novel Fifty Shades of Grey (2011) is one example of how unreliable sources lead to profound confusion and controversy within professional communities. Hollywood’s rendition of BDSM as scandalous titillation precedes public and professional understanding of what this alternative sexual expression truly entails (Allen, 2013). BDSM is also more likely to be misunderstood and pathologized by behavioral health professions. In particular, professional psychotherapists have contributed to the perpetuation of stereotypes by codifying uninformed personal bias and opinions into interventions purported to be therapeutic for this population. This codifying process is very similar to the historical interventions and treatments for people who are homosexual.

What Is BDSM?

The term ‘BDSM’ is an abbreviation that stands for a variety of concepts and consensual behaviors enacted within a particular relationship dynamic (Magliano, 2015). The term itself dates back to 1969 (Partridge et al., 2006). Within its wide range of expressions, activities, and definitions, BDSM also includes ‘kink,’ a broad colloquial term for non-normative sexual behavior.1 The general behaviors referenced here may include fetishistic interests, which may include wearing rubber, animal role-play (“furries,” “dressage,” puppy play), leather-sex culture and age play (“littles,” Daddy/girl or Daddy/boy), to name just a few (Bean, 1994; Hébert & Weaver, 2015; Miller & Devon, 1995; Taormino, 2012; Taylor & Ussher, 2001; Williams, 2006; Wiseman, 1996). Given the aforementioned scope and focus of this handbook, it is not possible to thoroughly outline all categories, subcategories, and scenarios within these specific lifestyles and fetishes. To do so would be voluminous. The most general, overarching and essential concepts will be presented and explored in relation to BDSM, its practice and practitioners. For a more in-depth and broad look at BDSM categories readers are referred to the reference list as well as Sexual Outsiders by Ortmann and Sprott (2013).

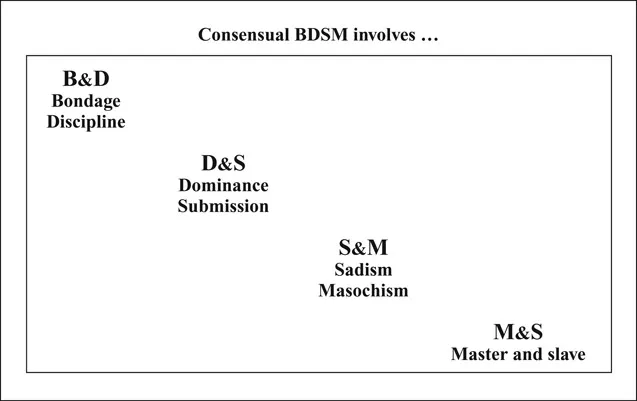

- The ‘B’ and ‘D’ traditionally stands for bondage and discipline, which include activities related to restraining and inflicting extreme sensations in the form of punishment.

- The ‘D’ and ‘S’ stands for Dominance and submission and pertain to the psychological aspects of control in which one person gives the orders and the other complies. This often takes place with a written social contract. This contract may outline protocols, expectations, limits, and boundaries.

- The ‘S’ and ‘M’ stands for sadism and masochism, usually simply known and written as “SM.”2 In the media and as part of scintillating titillation, the most vivid images of BDSM relate to inflicting and receiving intense sensation, like pain. In actuality, this may not necessarily be a part of any BDSM relationship.

- Finally, the ‘M’ and ‘S’ stands for Master and slave.3 This relates to a relationship dynamic between two consenting adults where one assumes varying degrees of authority and responsibility over a willing partner.

Strength of identification and affiliation with a common BDSM community and frequency of practice are primary determining factors that differentiate one who is curious or a fetishist from one who considers this as a part of their personal and/or sexual identity.

BDSM Practices

Consent is one of the most essential hallmarks of ethical BDSM practice (Barker, 2013; Fulkerson, 2010; Langdridge & Barker, 2007; Surprise, 2012). When adequate informed consent (permission) is provided, it is assumed that the practitioners understand the expected (intended) and potentially unexpected (unintended) outcomes of the BDSM activity or behavior that will be engaged in by the couple. Therefore, adequate consent is provided only when practitioners understand all known risks associated with the activity. Consent continues to remain even after unintended or unexpected outcomes that could not have been known when consent was initially provided. Clearly stated, consent is not retracted because of an unpredicted outcome.

Figure 2.1 Defining what the acronyms mean in consensual BDSM.

The activities represented by BDSM fall along a continuum ranging from egalitarian sensation play, represented on the left in our chart, to total authority exchange (which may or may not include sensation play or fetishistic activities) on the right (Hébert & Weaver, 2015; Midori, 2005; Moser, 2006; Newmahr, 2010; Rubel & Fairfield, 2014, 2015; Taylor & Ussher, 2001). Total authority exchange is also referred to as “consensual non-consent” or “total power exchange” (TPE).4 Authority exchange in general is also sometimes referred to as a “power dynamic relationship” or “power dynamic.” This relationship dynamic may last for a few hours during a scene, or as extensively as a full-time day-to-day discipline, and may involve a complex social and emotional contract (see BDSM Relationships section below for more discussion on this). On the sensation end of this continuum, there are a huge variety of physical activities that comprise BDSM and do not necessarily involve pain experiences (Turley et al., 2011). As one moves to the right along this continuum, there is an increase in the mental and emotional control one person exercises over another (Stein et al., 20...