![]()

1 The Pub

It may seem somewhat insulting to begin our reading of Australia in the pub. But Australians are both proud and ashamed of their enthusiasm for alcohol. The Australian image has had an alcohol problem from the earliest days of the colony, and pubs have interested the analysts of Australian culture for almost as long. On the one hand, they have proposed a nexus (bond or link) between one image of Australian masculinity and the huge consumption of beer, still regarding the pub as the beer-stained site of the notorious 'six o'clock swill'. On the other hand, populists defend the pub as the location of the authentic Australian values of mateship and egalitarianism. For Craig McGregor, 'drinking provides the focus of much Australian life ... the pub has partly replaced the dance hall as a convivial gathering place for men and women'. He sees drinking as 'a determinedly egalitarian activity, the great social leveller— except for a Test Cricket crowd there is no more classless place in Australia than a hotel bar.' [p. 136] This (from Profile of Australia) was written in 1967. McGregor would want to modify thi judgment now, partly because there have been significant changes in pub culture and drinking customs in the intervening two decades. Those changes and their underlying structures of meaning provide insight into important levels of Australian society.

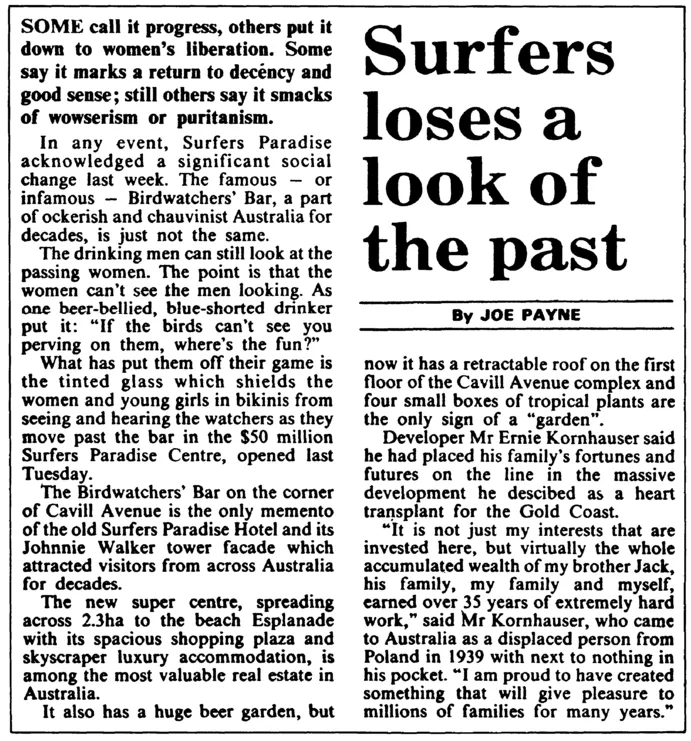

Revolution at Surfers Paradise

Surfers Paradise isn't usually regarded as the most likely place for a revolution, but fortunately such an event was recorded in December, 1984. The famous Birdwatchers' Bar, the glass-walled vantage point in the centre of Surfers Paradise where men could watch, heckle and whistle at passing women, has gone, or rather, has been

Bars, birds and change. Changes in the formal structure of pubs are connected with changes in the level of seriousness with which the needs of women are taken and the degree to which the pub is seen as entirely a masculine precinct. The compromise described in the renovation of the famous Birdwatchers' corner, may look like progress (and clearly the reporter sees it in this manner), but it leaves the basic position of the watchers unchanged. What it does is protect them from the accusation of sexism by allowing them to indulge in it privately. Still protecting the male, the pub's new windows transform him from predator to voyeur—an image of the change in male–-female relations in recent years. While updated and civilised, the pub still employs many of the same ideological principles embedded in its origins.

transformed. The terms through which this event are grasped by reporter Joe Payne are all weighted with cultural meaning. First there is the opposition between present and past, implicitly invoking an immemorial tradition (of at least twenty years) ended by the harsh realities of the present. The article announces its alignment towards the traditional past in the headline—Surfers has 'lost' something by the change, not gained anything new.

In the past that is invoked by Payne, the problem both raised and solved by pubs is the relationship between men and women. The terms of this relationship, at the old-style Birdwatchers' Bar, were 'male chauvinist', as all analysts readily agree, though not all would use those precise words. The pub was a male preserve, matching male preserves in many other cultures. But though the male-male relationship is normally seen as primary in the domain of the pub, the activity of the old Birdwatchers' Bar is a revealing exaggeration. The satisfaction, for the drinker, was not simply 'perving'—a displaced sexuality—but also being seen to perve, by women who would know and pretend not to respond. What the drinker missed was not simply the aggression of perving (which he can still indulge in through the one-way glass) but the complicity of women with that asymmetrical male power. Male solidarity, then, provides not so much a positive value in its own right, but a barrier protecting male sexuality and aggression from female counteraggression. The glib reference to 'women's liberation' in the report's first sentence is somewhat misleading, if it implies that the women's movement has been struggling for years to require men to look at women through one-way glass, but it does carry the obscure sense of male vulnerability to women that existed in the past as in the present. It was never the case that relations of man to man in a pub setting were offered as an autonomous and fully satisfying form of existence—real Australian males weren't homosexuals and were very disturbed at that accusation. What the Birdwatchers' Bar makes clear is the role of the pub world as a kind of anti-world, a bracketed space where the normative relationships of the real world were suspended or inverted, though only temporarily. Its cultural function was both to achieve that status and to control it; to limit it in place (the pub, not the home or workplace, or anywhere else) and time (the hours of business of the pub, whose opening and closing times are laid down).

The State, naturally, has always been concerned with regulation and control of this inherently antisocial activity and its legitimated sites. Australia stopped short of America's experiment with prohibition, and instead introduced six o'clock closing during the First World War. This upper limit, combined with a five o'clock end to the working day, created the legendary 'six o'clock swill', and this only slightly less repressive regulation lasted longer than prohibition, with effects on drinking customs in Australia that continue. In an interview in the American magazine Rolling Stone in 1984, the Australian rock band Men at Work regaled the reporter with memories of the swill in Melbourne, offering an apparently gratuitous account of local customs which it is highly unlikely that they were old enough to experience. This is the 'Legend of the Swill', with drinkers fighting for beers, vomiting and urinating where they stood in order to keep their places at the bar, tiles on the walls and floors, and lino-covered counters to lean against which could simply be hosed down after closing.

The six o'clock rule was repealed in New South Wales in the mid-1950s, and even later in some states, but as a myth it still has explanatory power about contemporary habits and conditions in pubs (as Men at Work recognised when they drew on it). Craig McGregor, again in Profile of Australia, had this to say:

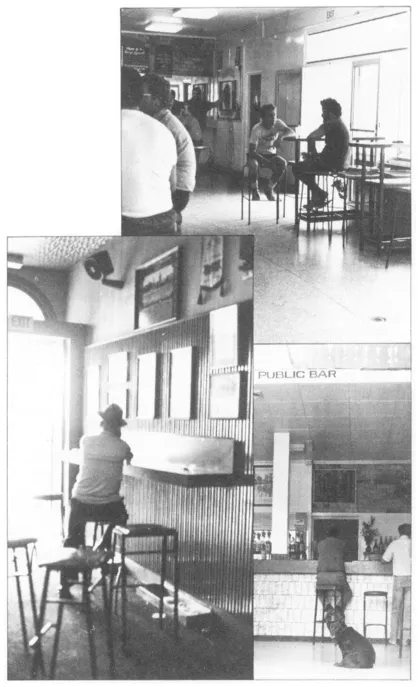

Once they were strictly utilitarian places, designed for hard drinking and nothing else: long, slops-wet bars which men could rest an elbow on as they drank standing up, lavatory-tiled floors and walls so they could be hosed down when the pub closed for the night, no chairs or tables to sit at, a couple of calendars pinned to the wall, a decrepit radio for listening to the races on Saturday afternoons, a large public bar, a small saloon bar, and tiny 'Ladies Lounge', and, so the publican hoped, a fiercedrinking clientele which didn't give the barmaids too much trouble by ordering fancy drinks. Most pubs are still like that, given over entirely to men in the bars, with faded old-fashioned beer posters in glass cases outside the swing doors and perhaps a chalk and black board counter lunch menu and a TV set jammed high in one corner of the bar as the only concessions to changing taste. [p. 136]

When he started the first long sentence with 'once', McGregor clearly thought he was going to contrast this utilitarian beastliness with something different and better, but by the time he finished the inventory he realised that not much had changed after all. There are signs of change, however, that qualify the dominance of the public bar and of an exclusively masculine pub culture. The growth of lounge bars and taverns and international-styled hotel bars has seen a real increase in numbers of women patrons. In Centrepoint Tavern in Sydney, for instance, one will see almost as many women as men on an average weeknight, many of them not accompanied by men. Yet such instances can still be seen as exceptions, whose significance is still read off from the dominant model. In spite of its seeming brutality, and claims that the social mores have radically changed, the traditional public bar retains its centrality and ubiquity, and rather than join either the knockers or the drinkers we must try to read it and understand the cultural necessity of its often puzzling features.

A Home Away From Home

The pub is a building, but more importantly it is a category of place, organised as one of a set of 'domains'. A domain in this sense is not simply a physical location. It is a social space, organised by a set of rules which specify who can be in it and what they can do. It also controls meanings: what meanings can be expressed and how, and how they will be interpreted.

Pubs have different functions in different communities. The role of a traditional country pub, for instance, grows out of a community with many characteristics different from those of urban populations. Limiting ourselves to contemporary metropolitan pubs, however, we can notice one initial classification in terms of location and function. There are, simply, city pubs and suburban pubs, with the majority in the suburbs. The temporal positioning of drinking in a typical day and week shows two peaks: one at lunchtime during the working day, and a larger one after work finishes, especially on a Friday night. The first peak is situated at an interface between work and work, and the second between work and home. The city pub is situated closer to the working place, the suburban pub to the home (although there are important class differences in places of working which we should not ignore, since they result in different kinds of pub and different kinds of pub culture). The pub is determined by relations to these two domains, the places of work and the home. Its function is to mediate their opposition by a complex set of repudiations and incorporations of both. So, on the one hand the pub can be called a 'home away from home', while on the other hand it can be seen as a major threat to domestic life. In fact one of the motives for the six o'clock closing was to protect the family home by ensuring that the husband spent his nights there (however incapacitated by the effects of the 'swill') rather than in the pub. Yet the interface with work relations is equally marked. The relationship with mates is a continuation of the unsatisfactory relations with others in the workplace, but transformed under better conditions. If the 'boss' joins 'the boys' at the pub it is now as an equal (almost) and as a mate, sharing a common male humanity. From these two relationships the pub gains its double character, as an anti-home and an anti-workplace.

Initially the classic pub format, so accurately described by Craig McGregor, reveals its status as an anti-home. This explains what is otherwise the most puzzling feature of pubs: their sheer drabness. The heart of the pub is the public bar, which is not only opposed to the saloon or lounge bar but even more to the domestic lounge room. We can list some contrasts:

| Domestic lounge | Hotel bar |

| Ostentatious decor | Spartan, utilitarian decor |

| Carpet or rugs | Tiles |

| Plush seats/sofas | Bar stools, places to stand |

| Well lit | Poorly lit |

| Quiet | Noisy |

| Oriented to display | Oriented to use |

In our discussion of the role of the lounge room in the suburban family home, in Chapter 2, we shall point out that it is public not private space, sacrificed to others, not for the self, even though it seems to be the self that gains the credit for the display. It is this kind of space that is most strongly repudiated by the public bar, in which self-display of this kind is specifically rejected in favour of an egalitarian ethos and private self-indulgence.

Essential here is the conception of social relations which the pub world exists to preserve and express. We can set up two lists again, as follows:

The domain of the pub. Despite renovations, the floor can still be hosed down at the end of the day, the occupants are still male, and the outside world is the cause of the retreat. Vinyl stools, laminex benches, tiled bars, dart boards and counter lunch menus are still the norm. In one of these bars, a TV set bore the admonition, 'To Be Used For Watching Sporting Events Only'. Diminished it may be as the dominant area in the pub these days, but its values are still preserved, and defended.

| Domestic lounge | Hotel bar |

| Family and friends | Mates and acquaintances |

| Mixed sex | Single sex (plus barmaid) |

| Hierarchical | Non-hierarchical |

| Fixed and permanent relations | Temporary relations |

| Asymmetrical obligations | Symmetrical obligations |

In this scheme we note that is not family relationships, especially the relationship of the husband and wife, that are repudiated here, so much as the repressive formality of the bourgeois family, in which intimacy and sexuality are suppressed as strongly, though differently, as in an all-male bar. It is in the lounge room that society asserts its benign control over the couple, imposing a male role of dominance which is qualified by a crushing set of obligations and duties, and a female role of domestic expertise and cheerful acquiescence in a life of service. It is the lounge room that the male escapes from, not the heart of the house-if it has one for him.

Instead of the fixed, oppressive hierarchical relations of the family lounge room, the public bar eschews hierarchy and permanence. It does have one obligation, or it did have: the 'shout', the obligation of every drinker to pay for his round in turn. Because it seems equal, it seems fair, though its equality is coercive: everyone is assumed to drink the same amount at the same speed. It is also immediate justice, not a nebulous system of deferred repayments, as when the hosts in the family home, having expended money and effort on entertainment for others, are invited back in due course to a similar occasion. Because the 'shout' is the main obligation imposed on drinkers, its refusal becomes the supreme crime against this specially constituted society. But the set of obligations are temporary, confined to the world of the pub, not tediously continuous like those of parents to children, for instance. This can make them seem irrational to an outsider. This can be seen in the response of the middle-class school teacher in the film Wake in Fright, to a truck driver who has invited him for a drink, and is refused: 'What's wrong with you people?' he asks. 'You can steal from you, rape your wife, but if you won't have a drink you're the worst in the world.'

A central figure who both links and opposes the pub and the domestic lounge is the barmaid. Like the wife, she is female. She fulfils the stereotyped female functions of happy service and provision of sustenance. But she contrasts with the wife at least in her 'wifely' role in the lounge room. She can be discreetly chatted-up, within strong, if unarticulated limits. Sometimes her sexuality is frankly a commodity (as in pubs offering 'topless' or 'see-through' barmaids) and in this way contrasts with the ideology of marriage (whatever is said about its reality). Most important, she does not represent the 'civilising' and repressive function of woman as mother, censoring bad language and 'dirty' talk, banning it even in adults from the decorum of the family home. What the pub offers, then, in a schematic, temporary and emotionally uncomplicated form is an alternative version of the dominant familial relationships. Since it is, in effect, a critique of those relationships, it is undoubtedly a threat to them, as has been widely recognised. Although it ostensibly confines that critique to the domain of the pub, the boundaries of domains tend to leak under pressure; and pubs leak more than most.

The conditions of the pub world are implicitly a critique of the dominant ideology of ...