![]()

1 | Surface Chemistry and Geochemistry of Hydraulic Fracturing |

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Man has been using fire as an energy source for almost half a million years. Mankind’s need for energy (fire, electricity, combustion engines, heating and air-conditioning, and so on: all kinds of everyday energy needs) has been increasing at a rate of about 2% per year (in proportion to the world population increase) over the past decades. Modern mankind (ca. 7 billion people) is thus totally dependent on energy (as related to food, transport, housing and building, medicine, clothing, drinking water, and protection against natural catastrophes (floods, earthquakes, storms, etc.) to sustain human life on earth. For example, one of the most energy-consuming essential products for sustaining life on earth for mankind is food. The major sources of energy during the past decades have been

• Wood

• Coal

• Oil

• Gas (methane)

• Hydro-energy

• Atomic energy

• Solar energy

• Wind energy, and so on

At present, oil (about 100 million barrels per day), gas (about 30% of oil equivalent), and coal (about 30% of oil equivalent) are the biggest sources of energy worldwide (Appendix I). The origin of coal (solid), oil (liquid), and gas (mostly methane) has been the subject of extensive research. Chemical analyses have shown that coal, oil, and gas (mostly methane) have been created inside the earth over millions of years from plants, insects, and so on (under high pressure and temperatures) (Burlingame et al., 1965; Levorsen, 1967; Calvin, 1969; Tissot and Welte, 1984; Yen and Chilingarian, 1976; Russell, 1960; Obrien and Slatt, 1990; Jarvie et al., 2007; Singh, 2008; Bhattacharaya and MacEachem, 2009; Slatt, 2011; Zheng, 2011; Zou, 2012; Melikoglu, 2014) (Appendix I).

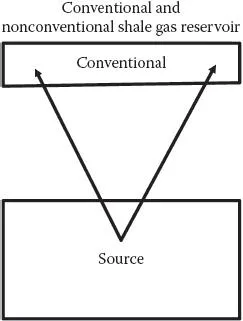

Furthermore, it is known that there are vast reserves of coal, oil, and gas under the surface of the earth. In this context, it is important to mention that the core of the earth is known to be a region of very high temperature (6000°C) and pressure (Appendix I) as compared with its surface (1 atmosphere pressure; average temperature around 25°C near the equator). This gradient in energy difference means that dynamics exist in the diffusion (migration) flow of fluids and gases. For example, it is reported that methane is present in the inner core of the earth. The flow takes place through fractures and fissures in the earth matrix. In other words, most of the phenomena on the surface of the earth are maintained at much lower temperature and pressure than inside the core of the earth. This also suggests that many fluids/gases (such as oil, lava, and gas) found in the inner core of the earth are at a higher potential compared with the surface of earth (in a low temperature and pressure state). This indicates that the natural phenomena on the earth are not static as regards physical and chemical thermodynamics. Hence, these materials (such as gases and fluids [lava, oil]) are able to migrate upward toward the surface of the earth due to the difference in energy through natural cracks and fractures (i.e., fluid/gas flow through porous rocks). Oil or gas is known to be found in two different kinds of reservoirs (Appendix I) (Figure 1.1):

• Conventional sources

• Nonconventional sources (source rock)

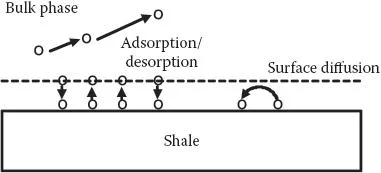

Conventional reservoirs are pockets in which the material (oil/gas) that has migrated from source rock has become trapped in the rock structure. Oil/gas has been produced from these conventional reservoirs for almost a century. The conventional reservoirs exhibit physico-chemical characteristics that are different from those of the source rocks (nonconventional) (i.e., from where the oil/gas material has migrated). As regards the origin of oil/gas, it is suggested that this has been generated from plants, animals, and so on over millions of years and is found to be trapped within the source rock (such as shale reservoirs). In a different context, one finds large reserves of methane in the form of hydrates in ice, in many parts of the globe (Kvenvolden, 1995; Aman, 2016; Bozak and Garcia, 1976) (Appendix I). The supply of oil and gas from conventional reservoirs has been decreasing during the past decades. This has resulted in an urgent need to explore new sources of energy. Both oil and gas have been found in some parts of the earth where the shale (oil/gas) reserves are known to be of very large quantities (e.g., oil reserves of over 10 trillion barrels!). Further, during the past decade, gas has been recovered from shale reservoirs (nonconventional) in large quantities (mostly in the United States and Canada). This technology is being extensively analyzed in the current literature, and there are some aspects that require more detailed analyses, since the physico-chemical phenomena in such processes are complex. In all kinds of phenomena in which one phase (liquid or gas) moves through another medium (such as porous rocks), the role of surface forces becomes important. In the current literature, one finds that the surface chemistry of reservoirs has been investigated at different levels (Bozak and Garcia, 1976; Borysenko et al., 2008; Scheider et al., 2011; Zou, 2012; Josh et al., 2012; Deghanpour et al., 2013; Striolo et al., 2012; Engelder et al., 2014; Mirchi et al., 2015; Birdi, 2016; Scesi and Gattinoni, 2009). This system can be described basically as being composed of macroscopic and microscopic phases (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.1 Oil/gas reservoirs are defined as (a) conventional or (b) nonconventional (source rock).

FIGURE 1.2 Shale gas reservoir (shale matrix–adsorbed gas–fractures [free gas]).

Shale gas reservoir structure: macroscopic structure-microscopic structure

The macroscopic technology is related to the design of pumps, pipes and tubing, transport, pressure regulation, and so on. The microscopic analyses are related to the essential principles of fluid and gas flow at the production well. This analysis is generally based on laboratory-scale experiments and data, using samples of reservoir rocks. The recovery process from shale reservoirs has been found to be different from those from conventional reservoirs. This is obviously as one would expect. One of the main differences arises from the use of horizontal drilling, which allows greater recovery than vertical drilling (Appendix I). Further, shale gas recovery is a multistep process:

• Step I: High-pressure water injection (with suitable additives and creation and stabilization of fractures)

• Step II: Gas recovery (desorption process and diffusion through fractures)

In Step I, the process is related to surface forces between water and shale. The initiation of the fracture process is where the molecules at the surface of the rock are involved. This means that surface forces determine the fracture formation. Further, the fluid flow will be described by the classical flow of liquids through porous material. The gas recovery (Step II) (i.e., gas desorption) is described from the solid–gas interaction theories of surface chemistry (Chapter 4). The first step is mainly the liquid flow through porous media. This is known to be related to capillary forces (Chapter 2). The second step is found to be the flow of gas (methane) through very narrow pores (Howard, 1970; Tucker, 1988; Civan, 2010; Javadpour, 2009; Allan and Mavko, 2013; Engelder et al., 2014; Yew and Weng, 2014). It is also suggested that most of the gas is in an adsorbed state (Hill and Nelson, 2000; Shabro, 2013; Ozkan et al., 2010). Experiments have shown that this is a reasonable assumption. It is reported that gas (mostly methane) is self-generating in shale, and that free gas and adsorbed gas coexist. Methane, as an organic molecule, will also be expected to adsorb to the organic (kerogen) part of the shale (Appendix I). The oil–shale (illite clay) adhesion characteristics have been investigated (Bihl and Brady, 2013). The impact of hydraulic fracturing and the degree of flow-back have also been studied.

The adsorption–desorption surface chemistry principles of gases on solid surfaces have been investigated in the literature (Adam, 1930; Chattoraj and Birdi, 1984; Adamson and Gast, 1997; Holmberg, 2002; Matijevic, 1969–1976; Somasundaran, 2015; Birdi, 2016) (Chapter 4). It is also estimated that 20%–80% of the total gas in place is present in the adsorbed state. The complex description of the gas shale reservoir is delineated in Figure 1.3. It is thus obvious that this technology requires a long-term production research and development approach. The surface area over which gas is adsorbed is also very extensive. Surface diffusion is the important step in the flow and recovery of gas (Bissonnette et al., 2015). If the pores are >50 nm (macropores), then the collision frequency between gas molecules will be expected to be greater than the frequency of collisions between gas and the solid surface. In the case where the gas molecule free path length is larger than the pore diameter, the frequency of collision between gas molecules dominates the process (the so-called Knudsen diffusion domain [Appendix II]). Surface diffusion dominates in micropores (<2 nm diameter). Accordingly, the pressure, the temperature, the solid surface, and the interaction parameters between the gas and the solid surface determine surface diffusion.

FIGURE 1.3 Gas-recovery process in shale reservoir: (a) adsorption–desorption; (b) diffusion in pores and surface diffusion.

This description of a shale gas reservoir is the most plausible in the current literature. The science of surface chemistry has been applied in various technologies (such as geology, geophysics, geochemistry, hydrology, reservoir engineering, petroleum exploration, biochemistry, paper and ink, and cleaning and polishing) (Birdi, 1997, 2003, 2014, 2016).

In any system where one material (oil, gas, or water) is flowing through given surro...