- 1,056 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Handbook of Carbohydrate-Modifying Biocatalysts

About this book

This book provides an actual overview of the structure, function, and application of carbohydrate-modifying biocatalysts. Carbohydrates have been disregarded for a long time by the scientific community, mainly due to their complex structure. Meanwhile, the situation changed with increasing knowledge about the key role carbohydrates play in biological processes such as recognition, signal transduction, immune responses, and others. An outcome of research activities in glycoscience is the development of several new pharmaceuticals against serious diseases such as malaria, cancer, and various storage diseases. Furthermore, the employment of carbohydrate-modifying biocatalysts—enzymes as well as microorganisms—will contribute significantly to the development of environmentally friendly processes boosting a shift of the chemical industry from petroleum- to bio-based production of chemicals from renewable resources.

The updated content of the second edition of this book has been extended by discussing the current state of the art of using recombinantly expressed carbohydrate-modifying biocatalysts and the synthesis of minicellulosomes in connection with consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulosic material. Furthermore, a synthetic biology approach for using DAHP-dependent aldolases to catalyze asymmetric aldol reactions is presented.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Basics in Carbohydrate Chemistry

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Classification of Carbohydrates

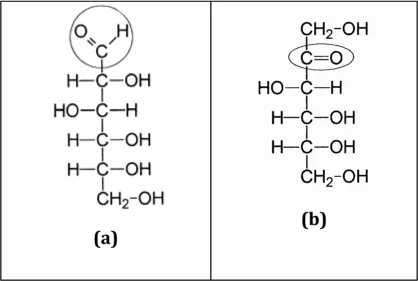

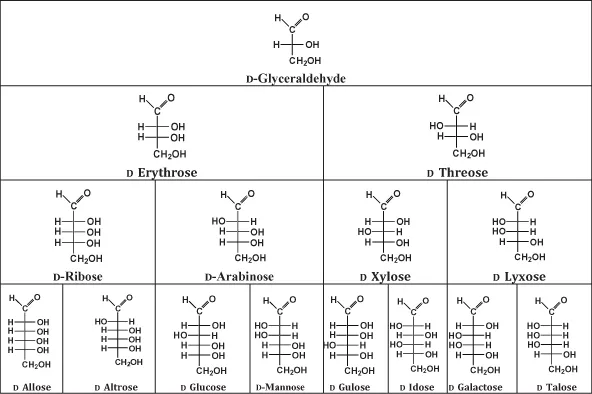

1.2.1 Monosaccharides

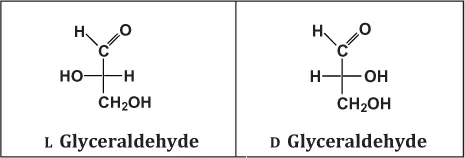

1.2.1.1 Configuration and nomenclature

1.2.1.2 Ring structures of carbohydrates

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Basics in Carbohydrate Chemistry

- 2 Glycoconjugates: A Brief Overview

- 3 Oligosaccharides and Glycoconjugates in Recognition Processes

- 4 Glycoside Hydrolases

- 5 Disaccharide Phosphorylases: Mechanistic Diversity and Application in the Glycosciences

- 6 Dihydroxyacetone Phosphate-Dependent Aldolases: From Flask Reaction to Cell-Based Synthesis

- 7 Enzymatic and Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Nucleotide Sugars: Novel Enzymes, Novel Substrates, Novel Products, and Novel Routes

- 8 Iteratively Acting Glycosyltransferases

- 9 Bacterial Glycosyltransferases Involved in Molecular Mimicry of Mammalian Glycans

- 10 Sulfotransferases and Sulfatases: Sulfate Modification of Carbohydrates

- 11 Glycosylation in Health and Disease

- 12 Sialic Acid Derivatives, Analogs, and Mimetics as Biological Probes and Inhibitors of Sialic Acid Recognizing Proteins

- 13 Enzymes of the Carbohydrate Metabolism and Catabolism for Chemoenzymatic Syntheses of Complex Oligosaccharides

- 14 From Gene to Product: Tailor-Made Oligosaccharides and Polysaccharides by Enzyme and Substrate Engineering

- 15 Synthesis and Modification of Carbohydrates via Metabolic Pathway Engineering in Microorganisms

- 16 Metabolic Pathway Engineering for Hyaluronic Acid Production

- 17 Microbial Rhamnolipids

- 18 Chitin-Converting Enzymes

- 19 Linear and Cyclic Oligosaccharides

- 20 Fungal Degradation of Plant Oligo-and Polysaccharides

- 21 Bacterial Strategies for Plant Cell Wall Degradation and Their Genomic Information

- 22 Heterologous Expression of Cellulolytic Enzymes

- 23 Engineered Minicellulosomes for Consolidated Bioprocessing

- 24 Design of Efficient Multienzymatic Reactions for Cellulosic Biomass Processing

- Index