- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Himalayan Bridge

About this book

The centrality of the Himalayas as a connecting point or perhaps a sacred core for the Asian continent and its civilisations has captivated every explorer and scholar. The Himalaya is the meeting point of two geotectonic plates, three biogeographical realms, two ancient civilisations, two different language streams and six religions.

This book is about the determinant factors which are at work in the Himalayas in the context of what it constitutes in terms of its spatiality, legends and myths, religious beliefs, rituals and traditions. The book suggests that there is no single way for understanding the Himalayas. There are layers of structures, imposition and superimposition of human history, religious traits and beliefs that continue to shape the Asian dynamics. An understanding of the ultimate union of the Himalayas, its confluences and its bridging role is essential for Asian balance.

This book is a collaborative effort of an internationally acclaimed linguist, a diplomat-cum-geopolitician and a young Asianist. It provides countless themes that will be intellectually stimulating to scholars and students with varied interests.

Please note: This title is co-published with KW Publishers, New Delhi. Taylor & Francis does not sell or distribute the Hardback in India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART - I

Himalayas: Geology, Genetics, Identity

1

India-Asia Collision and the Making of Himalayas

A critical evaluation and comparison of the available geological and geochronological data from the northern parts of the Himalaya and Trans-Himalaya mountains highlight that these mountains did not initially evolve by the collision of continents of the Indian and Asian plates. Instead, the subducted Tethyan oceanic lithosphere in front of the Indian continent melted to produce the calc-alkaline suite of the Shyok–Dras volcanic arc and the Ladakh batholith. Hence, the Indian plate initially subducted beneath and started building up the then existing intra-oceanic island arc. The timing of the first impingement of the Indian and Asia plates has been better constrained at around 57.5 Ma by comparing (i) the bulk ages from the Ladakh batholith (product of partial melting of the Tethyan oceanic lithosphere) with (ii) the subducted continental lithospheric and UHP-metamorphosed Indian crust in the Tso Morari, and (iii) biostratigraphy of the youngest marine sedimentation in Zanskar. Thus, the Himalayas witnessed their first rise and emergence from a deeply exhumed terrain in the Tso Morari after around 53 Ma, followed by a sequential imbrication of the Indian continental lithosphere and associated exhumation during the rise of the Himalayan mountains from the north to the south since 45 Ma.

Various palaeogeographic reconstructions of India and Asia since the Palaeozoic era have postulated that the vast Palaeo- and Neo-Tethys ocean spanned and separated the southern Asian plate and the northern Indian plate margins—this region now constitutes parts of the Himalayan and Trans-Himalayan mountain ranges like Ladakh, the Karakoram Mountains and the vast Tibetan plateau [1–3] (Figure 1a). In a relatively stationary Asian plate reference frame, the Indian plate converged northwards at about 180 ± 50 mm per year during 80 and 55 Ma and subsequently slowed down to 134 ± 33 mm per year at the collision which was not later than 55 Ma (Figure 1b) [4]. This movement coincided with the anti-clockwise rotation of the Indian plate, thereby impinging the Asian plate earlier in the northwest in contrast to its hit in the east [4]. The impingement of the Indian plate even persisted during the whole of the Cenozoic era and is still an ongoing process. Hence, estimating India–Asia impingement/collision is one of the most controversial topics in the Himalayan tectonics, as it is estimated anywhere between 65 and 35 Ma (refs 1, 5–18).

![Figure 1.1 a, Palaeogeographic reconstruction of the Neo-Tethys domain after the fragmentation of Gondwanaland and the movement of the Indian plate. Of interest is the Mesozoic passive platform on the northern Indian margin, the spread of the Neo-Tethys and development of the intra-oceanic Dras volcanic arc within the subduction zone. Redrawn after Stampfli and Borel [3]. b, Movement of the Indian plate with reference to Asia since 80 Ma and two points in the Himalayan syntaxes. Redrawn after Copley et al. [4].](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1641953/images/fig1_1-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 1.1: a, Palaeogeographic reconstruction of the Neo-Tethys domain after the fragmentation of Gondwanaland and the movement of the Indian plate. Of interest is the Mesozoic passive platform on the northern Indian margin, the spread of the Neo-Tethys and development of the intra-oceanic Dras volcanic arc within the subduction zone. Redrawn after Stampfli and Borel [3]. b, Movement of the Indian plate with reference to Asia since 80 Ma and two points in the Himalayan syntaxes. Redrawn after Copley et al. [4].

Evidences for the India–Asia collision and its timing are given below.

- (i) Palaeomagnetism: Convergence in the northward movement of the Indian plate and its slowdown took place at around 55± 1 Ma from the palaeomagnetic anomalies in the Indian Ocean [4, 7, 11].

- (ii) Palaeolatitude Evidences: The India–Asia suturing of the Tethyan succession in the Himalaya with the Lhasa terrane to the north took place at 46 ± Ma when these terranes started to overlap at 22.8 ± 4.20 N palaeolatitude [19, 20].

- (iii)Stratigraphy: (a) 56.5–54.9 Ma as the maximum age of initiation of the India–Asia collision was deciphered from a termination of the continuous marine sedimentation within the Indus Tsangpo Suture Zone (ITSZ) in Ladakh and 50.5 Ma was deciphered as the minimum age of closure of the Tethys along the ITSZ [17] or ~ 51 Ma (ref. 21). In this scenario, the Indian continental lithosphere travelled to the ITSZ trench at 58 Ma (ref. 5). (b) The final marine deposition in south Tibet at ≤ 52 Ma was a consequence of the initiation of collision and the onset of fluvial sedimentation ca. 51 Ma (refs 8, 9); this date was subsequently modified to 50.6 Ma (ref. 15).

- (iv)Sedimentology: Closure of the Neo-Tethyan Ocean during the earliest India–Asia collisional stage at ~ 56 Ma (ref. 18) is indicated from a renewed clastic supply to the Tethys Himalayan margin in Zanskar, fore bulge related uplift, evaporite nodules in the Upper Palaeocene and later red beds having caliche palaeosols [18]. The timing of the first arrival of the Asian-derived detritus in the uppermost Tethyan sediments provides another indication of the collision at ~ 50 Ma (ref. 22).

- (v) Magmatism: The Trans-Himalayan Ladakh batholith (LB) grew episodically and interruptedly with the very first small pulse at 105–100 Ma and subsequently between 70 and 50 Ma due to the melting of the subducting Tethyan oceanic lithosphere till 49.8±0.8 Ma to indicate the timing of the India–Asia continental collision [23–26]. This age is now constrained to 50.2±1.5 Ma as the initial collision age of the Kohistan–Ladakh Island Arc (KLA) with India along ITSZ and the final collision between the assembled India/Arc and Asia ~ 10 Ma later at 40.47±1.3 Ma along the Shyok Suture Zone (SSZ) by integrating U–Pb zircon ages with their Hf, whole-rock Nd and Sr isotopic characters [27].

- (vi) Metamorphism: The Indian continental crust was eclogitised in the vicinity of the ITSZ trench, when the ultrahigh pressure (UHP) coesite-bearing eclogite in Tso Morari was produced at 55± 7 Ma (ref. 10) or 53.3 ± 0.7, to be more precise [13, 14], while these are dated at 46 ± 0.1 Ma at Kaghan in Pakistan [16, 28].

- (vii) Integrated Geological Data: Two-stage events have been recorded in southern Tibet and elsewhere indicating a ~ 55 Ma collision of an island arc system with India (Event 1) and a younger Oligocene age of the India–Asia continental collision (Event 2) [29]. The two-stage Cenozoic collision has also been postulated from estimating the amount of convergence: 50 Ma collision of an extended microcontinent fragment and continental Asia, and 25 Ma hard continent–continent collision [30].

In the whole gamut of evidence for the India–Asia collision, the best possible age appears to be ~ 56 Ma—by correlating the geochronological constraints on the deep-seated metamorphism of lithosphere with the near-surface sedimentological facies and biostratigraphic age [11, 12].

It is, therefore, evident that the data on stratigraphy, sedimentology, palaeontology, geochronology, palaeomagnetism and palaeogeographic reconstruction provide different timings for the India–Asia collision. This chapter adopts a different approach to this intricate and difficult problem and evaluates the detailed geological and geochronological data from two tectonic units which were immediately juxtaposed across the ITSZ—the plate boundary along which the two plates converged and sutured in the NW Himalayas. It compares the ages of the two critical units as the products of changeover from the oceanic lithospheric subduction to the continental lithospheric subduction of the Trans-Himalayan LB on the southern edge of the Asian plate and the Himalayan Tso Morari Crystallines on the northern edge of the Indian plate respectively. An attempt is made to critically answer: (i) different tectonic units that were involved in the initial India–Asia convergence (ii) the timing of India–Asia impingement/collision and (iii) initial shaping of the Himalaya/Trans Himalaya.

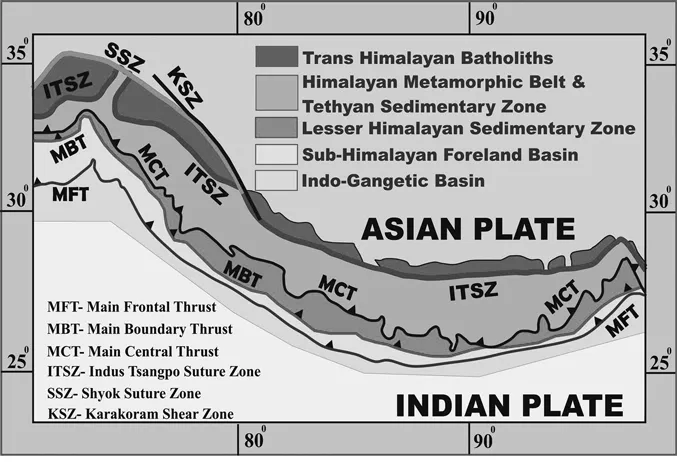

Geological Framework

In the northwest, the Trans-Himalayan Mountains, the Ladakh Range and the Karakoram Mountains demarcate the northern margin of the Himalayas. Drained largely by the river Indus and its tributaries, the Shyok and Nubra rivers, these mountains constitute the most inaccessible and difficult terrain in the northwest. As the Indian plate started subducting under the Asian plate, its Neo-Tethyan oceanic floor north of the plate melted at depth to produce the intra-oceanic Shyok–Dras Volcanic arc [31–37] (Figure 1). Between this arc and the Asian plate, a thick Palaeo-Mesozoic Karakoram sedimentary sequence was deposited on the southern Asian margin [31–37]. This ocean closed along two suture zones: SSZ in the north and ITSZ towards the south. These sutures demarcate the contact between the two plates and preserve the tectonic signatures of the following geological events from the north to south respectively [31–33, 35–41] (Figures 2 and 3).

- Initial Late Mesozoic subduction of the Neo-Tethys oceanic lithosphere along the SSZ during the Early Cretaceous–Lower Eocene with the intervening intra-oceanic Dras–Shyok volcanic island arc.

- Emplacement of the younger calc-alkaline Trans-Himalayan plutons to the south of SSZ (Figure 3).

- Final closure of the Neo-Tethys along ITSZ during the India–Asia collision.

Figure 1.2: Geological map of the Himalayas and Trans-Himalayas showing major tectonic units of the Indian plate, its contact with the Asian plate (ITSZ and SSZ) and location of the Trans-Himalayan batholith belt with a reference to the suture zones.

![Figure 1.3 Geological map of the northernmost Himalayas, Trans-Himalayas and Karakoram Mountains with lithounits of the southern Asian margin, extension of the Karakoram batholith, SSZ and KSZ. Two sutures, ITSZ and SSZ, contain fragmented oceanic crust pieces as ophiolites and are separated by the Trans-Himalayan Ladakh batholith. The UHP terrane in Tso Morari is juxtaposed against the southern suture. Compiled after the author’s work in Ladakh and Karakoram, published literature, and Jain and Singh [36].](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1641953/images/fig1_3-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 1.3: Geological map of the northernmost Himalayas, Trans-Himalayas and Karakoram Mountains with lithounits of the southern Asian margin, extension of the Karakoram batholith, SSZ and KSZ. Two sutures, ITSZ and SSZ, contain fragmented oceanic crust pieces as ophiolites and are separated by the Trans-Himalayan Ladakh batholith. The UHP terrane in Tso Morari is juxtaposed against the southern suture. Compiled after the author’s work in Ladakh and Karakoram, published literature, and Jain and Singh [36].

Further south of ITSZ, the Himalayan Metamorphic Belt (HMB) forms the leading edge of the remobilised continental India. It was covered by the vast Tethyan Palaeo-Mesozoic Sedimentary Zone (called as the Tethyan Himalaya), deposited on the northern passive margin of the Indian plate. The deepest parts of the leading edge of the Indian plate underwent UHP metamorphism in the Tso Morari area around 55 ± 7 Ma (ref. 10) or 53.3 ± 0.7 Ma (ref. 13) at a depth of mor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication Page

- About the Editors/Contributors

- Abstracts

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: Himalayas: Geology, Genetics, Identity

- Part II: Prism of the Past

- Part III: Mosaic of Politics

- Part IV: Philosophy, Art and Culture

- Part V: Spiritual Odyssey

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Himalayan Bridge by Niraj Kumar,George van Driem,Phunchok Stobdan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.