![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

A framework for exploring relations between lifelong learning and work in the computer era

D.W. Livingstone

Appeals for lifelong learning are a common response to the apparently increasing demands of work in advanced market societies. Growing information content of jobs, proliferation of information technologies based on micro-electronics and small computers, and widening global competition to produce more information-laden goods and services more efficiently are presumed to require greater learning efforts from both the current labour force and prospective workers. This book questions this widespread presumption and offers extensive empirical assessments of relations between work and learning. The basic question is: ‘What are the actual learning responses of adults to the demands of work in contemporary advanced market societies?’

A wider conceptual framework

The book is distinctive in basing its assessments on a more inclusive framework than prior studies for understanding relations between learning and work. The conceptual frame includes a continuum of formal and informal learning, and considers unpaid household work and volunteer work as well as paid employment. Prior research has ignored learning in household work and volunteer work, and has also given little attention to relations between formal education and informal learning in paid work.

Table 1.1 Forms of activity and learning

Basic forms of activity | | Forms of learning |

• Paid employment | | • Formal schooling |

• Unpaid household work | | • Further education |

• Community volunteer work | → | • Informal education |

• Leisure (sleep, self-care, hobbies) | ← | • Self-directed learning |

An adequate understanding of contemporary relations between learning and labour requires careful consideration of both unpaid as well as paid forms of work, and of informal as well as formal learning activities. As Table 1.1 suggests, in advanced market societies there are at least four conceptually distinguishable forms of basic activity (paid employment, household work, community volunteer work, and leisure including hobbies, self-care and rest) and four forms of learning (informal training, self-directed informal learning, initial formal schooling, and further or continuing adult education).

‘Work’ is now commonly regarded as synonymous with ‘earning a living’ through paid employment in the production, distribution and exchange of goods and service commodities. But most of us still must also do some household work, and many need to contribute to community volunteer work in order to reproduce ourselves and society. Both household work and volunteer work are typically unpaid and underappreciated, but they remain essential for our survival and quality of life (see Waring 1988). Household work, including cooking, cleaning, child-care and other often complex household tasks, has been largely relegated to women and gained some public recognition only as women have gained power through increased participation in paid employment. As community life has become more fragmented with dual-earner commuter households, time devoted to community work to sustain and build social life through local associations and helping neighbours has declined, and the productive importance of this work has been rediscovered as ‘social capital’ (Putnam 2000). All three forms of labour should be included in any careful accounting of contemporary work practices. Leisure refers to all those activities we do most immediately for ourselves, albeit often out of necessity, including sleep, self-care and various hobbies.

‘Learning’, in the most generic sense, involves the gaining of knowledge, skill or understanding anytime and anywhere through individual and group processes. Learning occurs throughout our lives. The sites of learning make up a continuum ranging from spontaneous responses to everyday life to highly organized participation in formal education programmes. The dominant tendency in contemporary thought has been to equate learning with the provision of learning opportunities in settings organized by institutional authorities and led by teachers approved by these authorities. Formal schooling has frequently been identified with continuous enrolment in age-graded, bureaucratically structured institutions of formal schooling from early childhood to tertiary levels (see Illich 1971). In addition, further or continuing adult education includes a diverse array of further education courses and workshops in many institutionally organized settings, from schools to workplaces and community centres. Such continuing education is the most evident site of lifelong learning for adults past the initial cycle of schooling. But we also continually engage, as we always have, in informal learning activities to acquire knowledge outside of the curricula of institutions providing educational programmes, courses or workshops. Informal education or training occurs when mentors take responsibility for instructing others without sustained reference to a pre-established curriculum in more incidental or spontaneous situations, such as guiding them in learning job skills or in community development activities. Finally, all other forms of explicit or tacit learning in which we engage either individually or collectively without direct reliance on a teacher/mentor or an externally organized curriculum can be termed self-directed or collective informal learning. As Allen Tough (1971, 1978) has observed, informal learning is the submerged part of the iceberg of adult learning activities. It is likely that, for most adults, informal learning (including both informal training and self-directed learning activities) continues to represent our most important learning for coping with our changing environment. No account of lifelong learning can be complete without considering people’s informal learning activities as well as their initial formal schooling and further adult education courses through the life course.

As will become evident in the following chapters, all of these basic activity and learning distinctions are relative and overlapping. For example, volunteer work may be done as preparation for paid work and also be paid (see Chapter 4). Among leisure activities, sleep may involve thinking about paid or unpaid work, hobbies such as making crafts may become works sold for pay, and self-care can be seen as work particularly when needed to prepare for paid work (see Chapter 7 and Matthews forthcoming). Most pertinently, virtually all other activities involve learning. To distinguish basic forms of activities, and even more so to distinguish different forms of learning, is primarily a means to emphasize the expansive character of both work and learning. The conceptual frames of many prior studies of work and learning have been preoccupied with paid employment and formal education and are far too narrow. Virtually all forms of human activity and learning are relational processes rather than categorical ones. Valuable flows of knowledge may occur among these four basic forms of learning and the other forms of our activities. The basic assumption in this book is that in information-rich societies all forms of work and learning are implicated in each other and cannot be effectively understood unless their interrelations are investigated.

General perspective

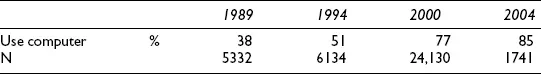

We can begin with two evident social facts. First, there has been a very rapid widening and deepening of use of computerized information technologies since the invention of small personal computers in the late 1980s, a period that may be termed the ‘computer era’. For example, Table 1.2 shows the growing prevalence of computer use among the employed Canadian labour force. In 1989, fewer than 40 per cent of workers were using computers in their paid workplaces; by 2004 over 80 per cent were. A greater amount of information is accessible to more people than ever before.

Table 1.2 Computer use in paid workplaces in Canada, employed labour force, 1989–2004

Sources: Statistics Canada 1989, 1994, 2000; WALL survey 2004.

Second, whereas the majority of married women with children in prior generations had devoted themselves largely to unpaid work, most now re-enter paid employment to continue their careers and/or make household ends meet. Between 1976 and 2003, the participation rate for Canadian women with children aged 6 to 15 grew from 47 to 77 per cent; for women with children under 6, it doubled from 31 per cent to 66 per cent. As a consequence, women’s general participation rate in paid employment reached 62 per cent by 2003. Whereas women made up only 31 per cent of the employed labour force in 1971, by 2003 they constituted 47 per cent (Statistics Canada 2004). While men’s labour force participation rate has declined marginally, the overall participation rate of the working-age population has reached the highest ever recorded level, with over two-thirds of all adults involved in paid employment.

So, there has been a very rapid computerization of paid work at the same time as the performance of unpaid work has become increasing problematic as the women who had previously done the bulk of it moved into paid employment. In this context, research attention to the lifelong pursuit of information and knowledge beyond formal educational institutions and particularly in both paid and unpaid work is very timely.

The general theoretical perspective used in the present studies posits an intimate connection between the exercise of workplace power and the recognition of legitimate knowledge, with greatest discrepancies between formal knowledge attainments and paid work requirements for the least powerful, including members of lower economic classes, women, visible minorities, recent immigrants, older people and those identified as disabled (Livingstone 2004). The present studies have been inspired by contemporary theories of adult learning that focus on the learning capacities of adults outside teacher-directed classroom settings, such as Malcolm Knowles’ (1970) work on individual self-directed learning and Paolo Freire’s (1974, 1994) reflections on his initiatives in collective learning through dialogue. Both theorists stress the active practical engagement of adult learners in the pursuit of knowledge or cultural change. General theories of learning by experience, emphasizing either the development of individual cognitive (Dewey 1916) or tacit (Polyani 1966) knowledge, also inform these studies. Other theories of cognitive development take more explicit account of subordinate groups’ socio-historical context (Vygotsky 1978). All of these approaches to adult learning encourage a focus on informal learning practices situated in the everyday lives of ordinary people. The studies of work and learning included in this book can be seen as contributing to increasing attention to this perspective (see Lave and Wenger 1991; Engestrom, Miettinen and Punamaki 1999; Livingstone and Sawchuk 2004).

All of these learning processes occur within advanced capitalist market economies, the most distinctive features of which continue to be: (1) inter-firm competition to make and sell more and more goods and services commodities at lower cost for greater profits (see Brenner 2000); (2) negotiations between business owners and paid workers over the conditions of employment and knowledge requirements, including their relative shares of net output (see Burawoy 1985); and (3) continual modification of the techniques of production to achieve greater efficiency in terms of labour time per commodity, leading to higher profits, better employment conditions or both (see Freeman and Soete 1994). These features lead to incessant increases in the types of commodities for sale, and shifts in the number of enterprises and types of jobs available. At the same time, popular demand for general education and specialized training increases cumulatively as people seek more knowledge, different specific skills, and added credentials, in order to live and qualify for paid jobs in such a changing society. Technological change, including tools and techniques and their combination with the capacities of labour, has experienced extraordinary growth throughout the relatively short history of industrial capitalism. Technological developments from the water mill to the steam mill to interconnected mechanical and electronic networks continually serve to expand private commodity production and exchange, while also making relevant knowledge more widely accessible.

The microelectronic computer era and the rise of global financial circuits have almost certainly contributed to the acceleration of these change dynamics of capitalist economies (Harris 1999). In rapidly globalizing markets, more and more people are drawn into the pursuit of waged labour, with an educational ‘arms race’ for formal credentials and consequent growth of underemployment (Livingstone 2009). Most notably for the current research, these dominant features of advanced capitalist economies drive workplace learning to become increasingly linked to computerization and unpaid work to become increasingly drawn towards paid work. The empirical studies presented in this book emphasize different aspects of work and learning practices. But all studies address a wide array of adult learning responses to the demands of computerization, the redistribution of paid and unpaid work or other recent workplace changes in contemporary advanced market societies; and all address connections between workplace power and recognition of knowledge.

Research methods

All studies include theoretically informed decisions in the selection and interpretation of evidence. Ensuring both representative selection and valid interpretation in the same study is extremely difficult – some would say impossible. In survey research, representativeness is typically considered to require random selection of a large number of respondents from a population. In interpretive case study research, more open conversation between the researcher and the researched is deemed necessary to reach valid understanding. Generally, survey researchers do not have the time, resources or disposition to achieve interpretive validity; interpretive researchers do not have the time, resources or disposition to achieve representative samples. Yet, surveys’ statistical profiles cannot tell compelling human stories; case study stories cannot address the question of the extent of the human conditions to which they speak; hence, the continuing quest to combine statistics and stories effectively.

The empirical studies reported in this book are based on a...