![]()

1 A quasi-colonial context

An imprint of decolonisation

Interventions by external forces have been highlighted as crucial elements impacting the construction of post-war identities in many modern Asian countries. Yet according to various physical conditions and different social forces, the representations in different cases are also various. Among all of them there are several remarkable similarities and differences that can be traced from Hong Kong and Singapore and contribute to an analytical platform for this research. In other words, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan can be regarded as three typical forms, briefly speaking, representing centripetalism, centrifugalism and nomadism of Asia Pacific architecture and urbanism.

When one reads the cases of Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan as representative examples in the context of Asia after the Second World War, the definite similarities are the most obvious and general points to legitimise the case study selections in terms of the focus on Asian countries’ spatial imprints of the external interventions, or more precisely, the decolonisation process since the end of the war. Amongst them, the dominant population of the so-called ‘Chinese Diaspora’ is immediate.1 According to official statistics, more than 90 per cent of modern Taiwan’s population has a consanguineous relation to various Chinese ethnicities; approximately 95 per cent of Hong Kong’s population was rooted in Chinese civilisation, which is slightly higher than Singapore’s 75 per cent Chinese community across its whole population. Ethnic compositions, in fact, not necessarily pure ethnic compositions – blurred ethnic imageries should be a more precise description instead – comprise the first important element when one examines the characteristics of any urban fields within the Asia Pacific context. Ethnic imageries represent cultures; dominant ‘ethnicity’ represents one specific region’s high culture; and high culture shapes representative, not exactly authentic but inarguably immediate and surface, urban landscape and architecture in its dominant region. For instance, Australia’s ‘white’ culture, although it comprises various Western ethnic groups, shapes the West-imagery culture and therefore West-imagery urban landscape in Australia. In China, a country comprising different ethnicities, the urban landscape is also shaped by its high culture, Han, which is established by an ideologically emerged ethnicity – the ‘Chinese nation’. Geopolitically, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore all have the character of maritime-based cultures when compared to the mainland cultures that correspond to them geographically. Unlike Europe, urban fields in the Asia Pacific, apart from capital cities, are relatively fragmental and in small scales. A characteristic that most of them share is that they developed from the coast or the riverbank because of Asia Pacific’s geographic condition. That is to say, the ‘mainland’ character of urban areas in the Asia Pacific, when compared to European metropolises, is less relevant. This urban geographic character is clearly evident not only in Hong Kong, Singapore and most cities in Taiwan but also in many metropolises in the Asia Pacific, such as Sydney, Jakarta, Manila, Ho Chi Minh City, Shanghai and Bangkok. Moreover, sometimes a colourful colonial past or an on-going colonial process in the present is another pivotal element with regard to Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, especially in the period up to the end of the Second World War when they were ruled by the Japanese Empire.2 The Asia Pacific, in terms of colonialism, can be put, interchangeably, into two categories, imperialism and globalism, which comprise a unique and complicated context different to Europe and other third world regions. In the first category, the Asia Pacific is a site including both imperialist colonies and imperialist ‘propers’ (a ‘proper’ being the ‘motherland’ of the colonised). Japan, for instance, not only achieved colonisation in the Asia Pacific, competing with the then European empires in the Asia Pacific, but also developed its empire internally. Some dictatorships in Asia have been transformed into semi-autocratic forms of governance, giving rise to quasi-colonialism, while in other cases compromised democracy has been the outcome – the Chinese Nationalists’ internal colonisation of Taiwan is one remarkable example. In the second category, globalism as a form of broad imperialism and a representation of globalisation today also has its impact on the Asia Pacific region. ‘Americanisation’ as a form of popular culture in Asia is one example. In architecture, global trends and modern technology contrasting with traditional forms, material and techniques are almost a universal phenomenon that ‘colonises’ the present built environment in the world. Finally, in resisting colonial influence, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore all construct cultural identities which oppose the so-called orthodox (mainstream) Han culture. Representations in languages clearly testify to this fact. The primary native language in Taiwan (Taiwanese), Hong Kong’s Cantonese and English and Singapore’s various southern Chinese dialects, the official language (English) as well as other non-Anglophone languages, are all able to demonstrate the different identities opposed to the mainstream modern Chinese language, Mandarin. This highlights the postcolonial element of urban Asia Pacific. The rise of ‘Otherness’, as posited by Edward Said in his book Orientalism (Said, 1978), is one phenomenon that is characteristic of the Asia Pacific. For instance, the use of other languages, no matter whether native or popular ones such as English, in place of an official or dominant language as a cultural form can be seen not only in Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan but also in Australia, Malaysia, Thailand and many Asia Pacific countries. In architecture and urban development, regionalism and the cultural revitalisation of either previously marginalised native cultures or previously repressed, externally introduced cultural legacies are prodigiously highlighted in recent built projects in urban Asia. The recent status of heritage conservation in Taiwan that focuses on Japanese-built buildings strongly confirms this. This postcolonial standpoint integrates the other elements and highlights an imprint of decolonisation in the present-day Asia Pacific.

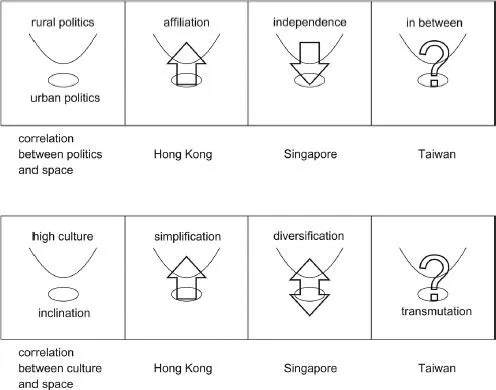

Figure 1.1 An analytical model of the post-war cultural politics between Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan. (Source: the author)

Although these similar points provide a platform from which to examine urban metropolises in the Asia Pacific, they are, however, too general to clarify the post-war scenario amongst Asian countries but merely assist in forming an analytical base. Indeed, by looking at the differences between the three cases and their spatial representations as well as the cultural-political interactions, certain issues in post-war Taiwan can be discussed and developed. This is initially observed from an abstract model which differentiates the cultural-political characteristics and the correlations with the spatial representations in Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan (Figure 1.1).

In looking at the interactions with the political context of each case, the relationship between rural and urban politics constructs the model when one reads the space as a text. This model suggests three typical forms of the urban built fields, as mentioned earlier, representing centripetalism, centrifugalism and nomadism respectively. Hong Kong is a typical example of the first urban field which shows the dynamic of a centripetal move in terms of its politics, culture and space. Examining the interaction between politics and space, the transfer of the sovereignty over Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997 has meant that the current political status of Hong Kong affiliates, as a relative rural political power, to the Chinese mainland: i.e. from the spatial contrast between a fine internationalisation and a dominant nationalism and between a geographic urban autonomy and a state autocracy. On the other hand, Singapore shows the opposite, a representation of the second form, originating when it announced its independence in 1965. Spatially, independence drew Singapore’s post-war direction from a regional localisation to a national internationalisation and from a subordinate city to a centralised city-state. By contrast, the case of post-war Taiwan shows an ambiguous situation somewhere in between and therefore a nomadic characteristic of its urban field.

From another point of view, a dominant high culture and an emergent cultural inclination indicate another correlation with space. First, based on its geographic and historical advantages, Hong Kong’s political affiliation with the PRC presents a cultural simplification which has been narrowed down from an international hybrid society to a comparatively Chinese-dominant society. Yet, on the other hand, without the burdensome considerations in geography and political economy from the Malay Peninsula, Singapore’s independence diversifies cultural movement as a result of the combination of its small geographic scale, its ethnic ties and its multi-racial population plus its new open-door economic policy. Nevertheless, with the similar awkward relationship to its political context, the case of post-war Taiwan shows equivocality amongst its dominant but transmutative shared Han culture society: its geographic segregation from China and the multi-aspects of its openness towards to the ocean and hence the world.

Amongst three forms, the third shows strong uncertainty while the first and the second move towards two opposite situations of the cultural politics of space – affiliating with or gaining independence from its cultural and political ‘relative’. Although the third form of the urban field indicates its unclear situation, this vagueness characterises one unique situation of the Asia Pacific in terms of its complicated postcolonial complex, e.g. India bears evident witness that it maintains an awkward relationship with British cultural politics – sometimes being intimate and sometimes antagonistic. Post-war Taiwan’s awkwardness in status and its wavering cultural-political conundrum, which caused forms of ambiguity in cultural identity and anxiety about locality in its architectural discourses and practices, is another remarkable example. The problematic issues of post-war Taiwan, from an architectural standpoint, then arise as follows: how do the physical spatial practices, in the field of architecture and urbanism, reflect this uncertainty in post-war Taiwan’s political and cultural chaos? To what extent does the trend of modern architectural and urban development in post-war Taiwan wander between two polar ends such as those chosen by Hong Kong and Singapore? How does the urban built environment of post-war Taiwan spontaneously represent the consequences of the conflict between this ideological anxiety and the pragmatic reality of its native society? These questions have to be answered from analyses of the unique nomadism of the Asia Pacific, which has different representations in terms of different positions between the two ends of the situation.

An issue-targeted comparison

A schematic context for these three forms, taking post-war Hong Kong, Singapore and early Taiwan’s spatial and cultural-political representations as examples, therefore has to be described first. This context, analysed here, is the contextual delimitation and starting point of this research on Taiwan. The spatial atmosphere constructed in Martial Law Taiwan was comparatively clear and simplified before the post-Martial Law scenario arose. After the law was lifted, the context and implications for post-war Taiwan became more complicated. Four emergent overall concerns of post-war Taiwan’s spatial evolution, which largely influenced the design strategies and identity construction in a quasi-colonial context, are listed and analysed through four quotations that indicate four different theoretical issues involved.

1: Patches and rags of daily life must be repeatedly turned into the signs of a coherent national culture.

(Bhabha, 1994)

Homi K. Bhabha’s idea of ‘everyday life’ appears to be the first hidden point amongst the observation of post-war Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. This highlights the notion that the issue of ‘state’ is no longer the most pivotal concern with regard to the context of the ‘quasi-colonial’ (no matter whether this means late-colonial, internal-colonial, postcolonial or new-colonial scenarios with different social, cultural conditions and representations) but instead it is the idea of ‘everyday life’. More precisely, Bhabha asserts that race, religion, patriarchy and homophobia are all the ideological forms of everyday life. That is to say, the realistic outline of society is closer to the necessities of everyday life rather than the operational nationalist strategies which would merely represent the collectivity of the transcendental minority (ruling authority).

The quotidian landscape of Hong Kong since the Second World War has changed in accordance with different conditions during different periods. Developing from a primitive fishing village, Hong Kong turned quickly and dramatically into an international port city once the colonial powers – the British Empire and the Japanese Empire – were involved. The everyday scenario of Hong Kong therefore was sophisticated from a simplified fishing life into trade, international, modern and Westernised society. The colonisation process in Hong Kong obviously changed its political dynamic. The representations of the everyday, however, told the detailed story of Hong Kong’s urban landscape. The image of a primitive southern Chinese fishing village was suddenly turned into that of an international trade port in 1842; since then, Western architecture and modern urbanisation have been introduced. In less than four years, between 1941 and 1945, Japanese culture had infiltrated into Hong Kong’s educational system and introduced social policies which impacted on its daily routines as well as urban landscape. Street names, urban and religious landmarks, during that period, started to be further hybridised and complicated amongst southern Chinese, Western and Japanese cultural elements. Before and after 1945, when the British was reclaiming the ruling power from the Japanese, Hong Kong society started to face its fate of high density when there was a sudden increase in population; this was due to an influx of émigrés from China caused by the founding of the PRC and the war-time chaos in China during the Second World War and the Chinese Civil War. Northern Chinese images, for instance, had been added into Hong Kong’s everyday life. Confrontations amongst different ethnic groups, political forces, religious forces and cultural legacies therefore forged the basis of Hong Kong’s modern urban landscape. From the 1970s onwards until 1997, Hong Kong society moved towards stability and prosperity; its high-density and internationalised population shaped the general imagery of today’s urban architecture in Hong Kong. Yet the nature of Hong Kong’s urban landscape was not so much fixed as changeable; the PRC, which took over sovereignty from the British in 1997, adds a variable into Hong Kong’s quotidian condition. New social policies and systems which incline towards the mainland heavily reshape Hong Kong’s day-to-day urban landscape owing to a considerable increase of mainland visitors and interventions into Hong Kong’s daily routines. The real estate industry that is currently impacted by this situation and is therefore reorganising the existing streetscape of Hong Kong using mainland Chinese investment is one remarkable example. These changes, from the spatial point of view, are indirectly connected to the issue of ‘state’ but directly associated with the everyday of Hong Kong which is actively pushed by its ‘cultural politics’ instead.

The change in the nature of Singapore’s everyday landscape was activated by motivating events similar to those in Hong Kong but it results in different presentations and moves in dramatic directions. Singapore also moved into a social and cultural-political sophistication owing to British and Japanese colonisation from a Malay island. Owing to its geostrategic relationships with these colonial forces and various political forces from the Asian continent, e.g. with Malaysia and China, Singapore reflects even more colourful representations in its everyday landscape in terms of its ethnic communities, languages and cultures. Joining the Federation of Malaya in 1963 distanced Singapore from British control, but in 1965 it gained independence and joined the Commonwealth, which moved it in a different direction from that of Hong Kong. Being geographically and racially complex, Singapore’s quotidian face is always open and diverse, and this becomes the one unique characteristic, including both harmonious and conflicting representations, that shapes Singaporean urbanism. This everyday face gained its balance through a neutral imagery which had been ideologically added into its streetscape by the new government after independence. Targeted at internationalisation, this neutral imagery forges modern and new construction of urban architecture as well as infrastructure in Singapore and provides a space of public sphere reorganising its complex social and cultural everyday life. Everyday life again in the case of Singapore plays an immediate motif of shaping its urban landscape. Although political involvement can never be eliminated from the context, the ‘cultural politics’ that is associated with the daily routines is the more precise issue when its spatial representation is examined.

In considering the case of post-war Taiwan, a series of questions again arise when compared to Hong Kong and Singapore. What is the typical representation of the built environment in post-war Taiwan which shaped a general understanding for the public? What is the corresponding spatial tendency when Martial Law was lifted? Is the spatial ethos which interplays with the cultural politics in Taiwan, from the early post-war period to the present, different to the scenarios in Hong Kong and Singapore? What are the spatial strategies and reality in post-war Taiwan in such a similar quasi-colonial context? These questions are unfolded along with the perspective of everyday life by analysing three other essential concerns below – the issues of ideology, multiplicity and subjectivation.3

2: Hey, you there.

(Althusser, 1994)

Louis Althusser believes that ideology is an illusion which is a representation of the ...