eBook - ePub

Integrating Climate Change Actions into Local Development

- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Integrating Climate Change Actions into Local Development

About this book

To date, climate change adaptation and mitigation have been treated separately both in research and in the climate negotiations. However, a growing body of literature is now being developed that points to actual and potential synergies and trade-offs between responses to climate change and sustainability. This literature has evolved in a spontaneous way with diverse approaches and no common methodology to help practitioners explicitly plan for these synergies. This special issue of the Climate Policy journal addresses this gap between scientific knowledge and practitioners' needs by focussing on linkages between climate change and sustainable development at the level of conceptual framework and methods. In particular, the papers address in an integrated way local development options involving both adaptation and mitigation in order to promote resilience to climate change in human and natural systems. The special issue provides policy and methodological guidelines for linking local deveopment pathways with responses to climate change, based on collaboration between local practitioners, the public and scientists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Scale and sustainability

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37831–6038, USA

Geographical scale is a factor in interactions between climate change and sustainable development, because of varying spatial dynamics of key processes and because of varying scales at which decision-making is focused. In a world where the meaning of ‘global’ and ‘local’ is being reshaped by technological and social change, a challenge to sustainable development is realizing the impressive, but often elusive, potentials for climate-change-related actions at different scales to be complementary and reinforcing. Climate change adaptation is suggested as an example.

Keywords: adaptation; bottom-up; cross-scale; governance; multi-scale; scale; sustainability actions; sustainable development; top-down

L’échelle géographique est un facteur dans l’interaction entre changement climatique et développement durable, étant donnés les différentes échelles spatiales encadrant les processus clés et la prise de décisions focalisée à différentes échelles. Dans un monde où le sens des mots «mondial» et «local» est redéfini par les changements technologiques et sociaux, un enjeu relatif au développement durable est de réaliser le potentiel prodigieux mais souvent insaisissable de complémentarité et de synergie des actions la lutte contre le changement climatique applicables à différentes échelles. L’adaptation au changement climatique est proposé en tant qu’exemple.

Mots clés: actions durables; adaptation; bottom-up; développement durable; échelle; gouvernance; inter-échelle; multi-échelle; top-down

1. Introduction

Interactions between climate change and sustainable development are expressions of an ever-changing dance that happens at a variety of geographical scales, and appreciating this dance is one of the keys in assuring that sustainability can be realized.

This article considers how geographical scale is a factor in climate change/sustainable development interactions, especially in determining what kinds of actions are best focused on which scales and how actions at different scales may affect each other. First, it summarizes the conceptual starting points in a world in which the meanings of such constructs as ‘global’ and ‘local’ are being reshaped by technology and other forces of change. Next, it addresses ways in which scale is an aspect of sustainability, with brief examples. It then focuses on ways in which scale relates to sustainability actions. Finally, it turns to potentials for making climate-change-related sustainability actions at different geographical scales complementary and reinforcing, rather than unrelated or even in conflict, using climate change adaptation as an example.

2. Conceptual foundations

For the purposes of this article, geographical scale is defined as the spatial dimensions of a process, an observation, or a decision (see Capistrano et al., 2003). Sustainable development is defined as development that meets the social and economic needs of the world’s population, current and future, without endangering the viability of environmental systems important to meeting those needs. In many cases, however, current understandings about relationships between scale and sustainable development are rather similar even if the definitions vary to some degree.

Scale can be viewed as a continuum between micro (very small) and macro (very large) (Meyer et al., 1992), but in practice the processes that drive and shape sustainability tend to organize themselves more characteristically at some scales than others, giving the sustainability scale continuum a kind of lumpiness (Wilbanks, 2003a). In many cases, reflecting this lumpiness, scales related to particular levels of system activity can be represented as mosaics of ‘regions’, each reflecting a characteristic scale, with smaller-scale mosaics apparently nested within larger-scale mosaics (Costanza et al., 2000) – which tends to invite speculations about spatial hierarchies, whether relevant to process relationships or not.

Geographical scale, of course, is not the only kind of scale important for sustainability (Cash et al., 2006). For instance, along with scales (or ‘levels’) of organizational structure, scale is a factor in time as well. Drawing on the literature in such fields as ecology, there has been a tendency to associate spatial and temporal scale: e.g. suggesting that sustainability-relevant time-scales in larger geographical areas are longer, while time-scales in smaller geographical areas are shorter (Capistrano et al., 2003), although many exceptions can be noted (such as the time horizons of some elected officials at national scales).

In any case, appreciating the roles of geographical scale for sustainability is profoundly complicated by constant changes in the world around us, especially as technologies reshape the meaning of proximity and increase interconnections over what were once long distances (Wilbanks, 2003b), often speeding the diffusion of innovations. Some alternatives for interaction appear to be released from distance constraints by technologies (and associated cultural changes) such as cyberspace.

Observers of global processes see a ‘shrinking’ globe, as distant neighbours become nearer neighbours (e.g., Harvey, 1989). Observers of local processes see areas in a mosaic being transcended by nodes in networks, as individual contact networks become less dominated by geographical proximity. Meanwhile, technology is changing the character of places by shaping what happens there, and it changes social demands for nature’s services and tools for environmental management (Wilbanks, 2003b).

This suggests that familiar conceptions of physical scale are, at least in many parts of the developed world, evolving into a kind of virtual scale, which is changing the meaning of scale, location and locality in ways that are not yet fully understood.

3. Scale as an aspect of sustainability

Scale is an aspect of sustainability in that sustainable development involves differences between scales in systems and processes, understandings of issues, and abilities to act; relationships between scales in systems and processes, and in shaping each other’s perceived realities and one’s ability to act; and potentials for multi-scale analyses and actions (Wilbanks, 2003a; Kates and Wilbanks, 2003; Purvis and Grainger, 2004).

We know, for example, that sustainability in a neighbourhood is different from sustainability in a nation, and we know that sustainability in a localized ecology is different from sustainability in a regional ecosystem (Holling, 1995). We also know that what happens with sustainability at one scale affects sustainability at other scales. For instance, the subglobal component of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment reported that, in some parts of the world, local situations are not sustainable while their larger regional situations appear to be relatively stable; while, in other parts of the world, local situations are quite stable while their larger regional situations appear to be in a state of crisis (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005).

A part of the explanation for this divergence in perceptions – and realities – is that sustainability may be viewed differently at different scales, and relevant information may not be the same (Rebozatti, 1993; Wilbanks and Kates, 1999). In many cases, for instance, there are differences between scales in complexity and in vulnerability (Eriksen and O’Brien, 2007). Smaller scales exhibit less complexity but, as a result, are more tractable in tracing out relationships in all their richness, while larger scales include more complexity but can only be addressed by simplifying the relationships in order to make analysis and understanding manageable (Kates et al., 2001). Regarding vulnerability (e.g. to severe weather events due to climate change), smaller scales have a lower probability of threat but less resilience if that threat were to be realized, while larger scales have a higher probability of threat somewhere within them but more resilience in coping with the threat, because as a general principle they have access to a wider range of resources for damage response and cost-sharing.

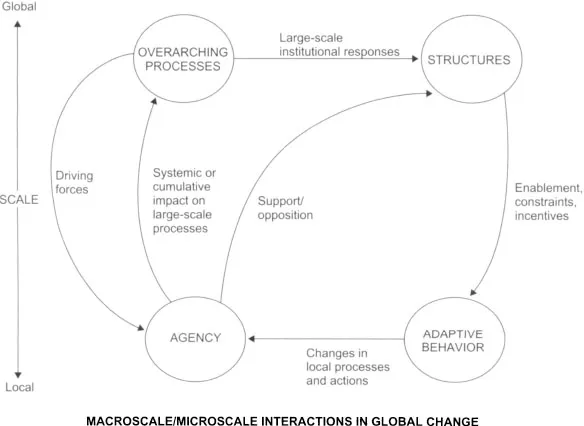

The different scales, however, are not independent of each other. As Figure 1 indicates, processes and actions at scales from local to global interact constantly, and these interactions can pose a number of challenges to sustainability (Cash et al., 2006; Wilbanks et al., 2007a). Top-down forces can threaten an insensitivity to local contexts, a backlash from disenfranchised local stakeholders, and a lack of empowerment of local creativity. Bottom-up forces can threaten an accumulation of relatively small changes that add up to very large changes (Turner et al., 1990), a lack of sensitivity to larger-scale driving forces and issues, a lack of information about linkages between places and scales, and a lack of access to resources to support effective actions.

FIGURE 1 Macroscale/microscale interactions in global change. Adapted from Wilbanks (2003a).

The fact is that sustainability is not a state; it is a trajectory of change (Wilbanks, 1994), depending on constant adjustments to both internal and external driving forces, both of which are subject to sometimes spontaneous and sometimes unpredictable changes, from technological innovation and socio-political leadership to biological mutation. In this regard, not all localities are shaped by every change at a larger scale; and not every large-scale system is affected by every change in every locality. But sustainability in any one place is to some degree threatened by a lack of sustainability in any other place, because ripple effects from non-sustainable circumstances can have far-reaching implications, from environmental migration to resource scarcity to roots of terrorism (Cutter et al., 2003).

Scale is also a factor in how we view and learn about sustainability (Wilbanks and Kates, 1999; AAG, 2003; Kates and Wilbanks, 2003). Sustainability is a challenge in multidisciplinary integration, and a major finding of sustainability studies over the past several decades is that such integration is most feasible if it is place-based (NAS, 1999; Kates et al., 2001; Wilbanks, 2003c). In many cases, it appears that responses to sustainability challenges that effectively integrate understandings of both natural and human systems, such as potentials for adaptation to climate change, depend heavily on locationally specific contexts, options, and avenues for action (Burch and Robinson, 2007).

Moreover, sustainability issues may appear different according to whether they are examined top-down or bottom-up. For instance, top-down analyses are strongly shaped by input assumptions that may not be appropriate for every locality, while bottom-up analyses can be so case-specific that extracting general lessons is difficult (Wilbanks, 2005; Wilbanks et al., 2007a).

Illustrations of scale as an aspect of sustainability are all around us. For instance, population growth is a global-scale driving force, but many of its implications are highly localized: e.g. historically, pressures in mainland Southeast Asia to make the painfully difficult socio-political transition from shifting agriculture to wet rice cultivation or, more recently, issues of equity in connection with larger-scale requirements for waste disposal in order to support economic growth.

Imbalances in the global carbon cycle, of which climate change is the most salient effect, are rooted in every aspect of scale relationships in our planet’s coupled nature-society systems, as depicted in Figure 1. Global driving forces such as population and economic growth and technological change pour down upon localities hungry for opportunities and newly aware of alternatives as the information technology revolution spreads. Local actions seeking new comforts, conveniences, mobility and job opportunities – in the context of these driving forces – produce carbon emissions that add up to rising total emission curves. The resulting increases in radiative forcing at a global scale feed back downward as changes in climate and associated impacts on temperature, precipitation, extreme weather events, and the sea level. Impacts (or concerns about impacts) at local and regional scales join together to push for actions at national and global scales; in fact, without such bottom-up encouragement, effective actions by larger scales tend to be limited in democratic systems of government. Larger-scale actions are then shaped and fine-tuned in association with smaller-scale stakeholders and, in fact, in large part implemented through smaller-scale actions, whether related to carbon emission source reductions or sink enhancements (Burton et al., 2007). If the results are not sufficient to address imbalances and associated impacts, the process iterates further.

4. Scale and sustainability actions

Often, views of the relevance of scale in sustainability actions have reflected different academic disciplinary perspectives, e.g. political scientists interested in global-scale governance structures contrasting with cultural anthropologists interested in local-scale knowledge (Cash et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2006a). A challenge has been to find ways to knit these perspectives together to combine the insights of all (Reid et al., 2006b).

Several things are known at a relatively high level of confidence.

1. We know that decision-making based on broad societal participation requires personal interaction. There is abundant evidence that many decisions are shaped by personal communications, which relate to what has been called a ‘choreography’ of human interaction (Parkes and Thrift, 1980; after Hagerstrand, 1975). Where those personal interactions benefit from physical proximity, there tend to be physical limits to the social and spatial scale at which consensus or accommodation can be reached for some purposes. Clearly, proximity contributes to decision-making as a social process, connecting with such issues as empowerment, constituency-building and public participation. In this sense, participative decision-making has a strong scale component, although changes in information technologies and associated social patterns may be shifting some aspects of participation towards involvement in electronic communication networks rather than direct personal interactions.

2. We know that many of the systems, pro...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Aims and scope

- About the contributors

- Linking climate change and sustainable development at the local level

- Scale and sustainability

- Making integration of adaptation and mitigation work: mainstreaming into sustainable development policies?

- A framework for explaining the links between capacity and action in response to global climate change

- Understanding and managing the complexity of urban systems under climate change

- Vulnerability, poverty and the need for sustainable adaptation measures

- Structured decision-making to link climate change and sustainable development

- Integrating adaptation into policy: upscaling evidence from local to global

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Integrating Climate Change Actions into Local Development by Livia Bizikova,John Robinson,Stewart Cohen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Ecología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.