![]()

Part I

Governing the Urban Climate Challenge

Understanding the Role of Cities in the Global Climate Regime

![]()

1 Introduction

Urban Resilience, Low Carbon Governance and the Global Climate Regime1

Craig Johnson, Heike Schroeder and Noah Toly

Introduction

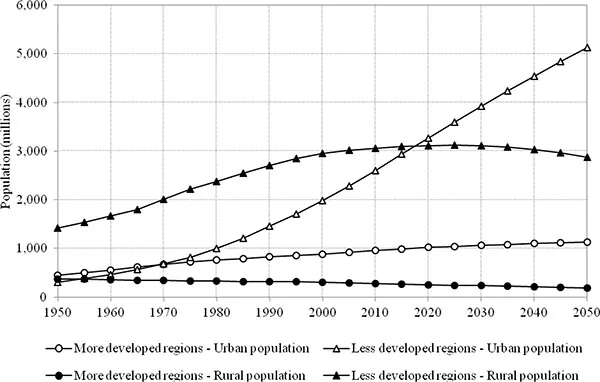

Urbanization has emerged as a major theme in world politics. For the first time on record, the number of people living in urban areas has exceeded the world’s rural population (Satterthwaite et al., 2010: 2809). According to the United Nations, the world’s urban population is projected to grow by another 3 billion people by the year 2050, increasing demand for clean air, water, land and essential public services, and putting unprecedented pressure on these and other resources (McDonald et al., 2011: 1). Most of the growth in urban population is expected to occur in the developing world (Figure 1.1).2

By virtue of the fact that they concentrate significant resources and numbers of people, cities are highly vulnerable to climatic hazards, such as floods, heat waves, storms and water-borne disease, especially in low elevation areas (McGranahan et al., 2007; Munslow and O’Dempsey, 2011; McDonald et al., 2011; Adamo, 2010; Romero-Lankao and Dodman, 2011). According to the 2011 Revision of the World Urbanization Prospects (UN/DESA, 2012: 18), 39 of the 63 urban areas with populations greater than 5 million are located in areas with a high risk of flooding, cyclones or drought; 72 percent are located “on or near the coast,” two-thirds are in Asia.3

At the same time, cities are also major emitters of greenhouse gases. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA, cited in World Bank, 2010), cities now account for 74 percent of the world’s carbon consumption.4 Left unchecked, rapid urbanization will have a profound effect on the world’s demand for renewable resources, creating new forms of vulnerability within cities, but also far beyond the urban footprint (IPCC, 2014: Chapter 8). Indeed, it is no stretch to suggest that processes of urbanization are the most significant forces shaping the global environment.

Improving the ability of cities to mitigate and adapt to climate change is therefore a pressing global priority. This book is about the ways in which cities, transnational urban networks and global governance institutions have repositioned themselves in the context of urbanization and global climate change. It starts from the premise that urban engagement with international climate policy discourses has influenced new forms of urban and global climate governance that are as yet poorly understood. Drawing upon contributions from scholars working in the fields of global environmental governance, urban sustainability and climate change, the volume explores four questions that have strong bearing on the ways in which we understand and assess the changing relationship between cities and the global climate regime.

- First, how and in what ways are cities incorporating climate change into urban planning and policy?

- Second, what is the impact of international climate change norms on urban and domestic climate policy?

- Third, how are cities and transnational urban networks engaging with global climate governance politics?

- And fourth, what are the implications for the study of international relations and global climate governance?

Figure 1.1 Urban and rural population growth trends and projections: 1950–2050.

This chapter introduces the volume by reviewing the state of existing knowledge about the ways in which cities have been conceptualized in the field of urban and global climate governance. In so doing, it explores the ways in which climate change considerations have been articulated and disseminated through the global climate regime, a term we use to describe the rules, norms and procedures that have been established through the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (hereafter UNFCCC). This is not to suggest that the international climate regime is only or primarily a function of the UNFCCC. Rather, it implies that urban engagement in international climate policy discourses has been framed by the norms and institutions established by the UNFCCC, an assumption we explore more critically in due course.

First, however, we begin by describing the urban climate challenge.

The Urban Climate Challenge

Empirical insights about the impact of urban systems on global emissions raise important questions about the extent to which cities can act autonomously and collectively to develop alternative industries, technologies and institutions that may encourage more sustainable patterns of consumption and production. At the international level, considerable attention has been paid to the capabilities of national governments to forge new commitments to support deep and meaningful cuts in emissions while at the same time investing in adaptation measures (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005; Betsill and Bulkeley, 2006; Toly, 2008; Kern and Bulkeley, 2009; Bulkeley, 2010; World Bank, 2010; IPCC, 2014: Chapter 8). In recent years, cities like Toronto, New York and Seattle and transnational urban alliances, like the C40 and the International Council on Local Environmental Initiatives, have forged new commitments of their own, often in parallel to the post-2012 framework.

Whether cities will make a difference in terms of actually reducing emissions and vulnerability to climate change will depend on the will and ability of municipalities, corporations and civil society organizations to effect meaningful change at the local level by investing in infrastructure and institutions that can be replicated and maintained in the face of future social and environmental stress (World Bank, 2010; Atkins, 2012). But it will also depend on the ability of cities to support policy initiatives that work with a wider range of state and non-state actors whose diverse interests, actions and institutions have important bearing on the ability to engage in mitigation and adaptation at wider scales of interaction.

In theory, new sources of international funding (like the Green Climate Fund) will provide an important means of investing in adaptation and mitigation measures that may reduce emissions and vulnerability to climate change (World Bank, 2010; Kennedy, 2011). However, the ability of cities to invest in “climate smart” technologies that can lower emissions while at the same time building resilience to climate change is limited. Urban infrastructure, for example, often persists for decades and sometimes lasts for centuries. Overcoming the rigidities put in place by years of investment (or lack thereof) in particular modes of transportation, electricity generation, sanitation, water treatment and so forth entails an ability to understand the costs and potential risks of maintaining the status quo and an ability to mobilize (public and private) resources in the name of (long-term) infrastructural development (cf. Moser and Luers, 2008; World Bank, 2010; Kennedy, 2011; IPCC, 2014: Chapter 8). In some cases (e.g., raising transmission boxes and insulating electrical cables in New York), investing in resilience can be relatively straightforward (Klinenberg, 2013). In others (e.g., building the 10,000ha Marina and Barrage Reservoir in Singapore or the Delta Works/Climate Proof Program in Rotterdam), it can span generations (Klinenberg, 2013).

Promoting higher-density settlement is often advanced as a means of reducing urban emissions, especially in transportation and building systems (World Bank, 2010: 19; IPCC, 2014: Chapter 8). However, higher-density living can also exacerbate traffic congestion if personal car ownership is high, which leads to further emissions.5 Moreover, the factors affecting urban demand for land, energy and resources are arguably part of a wider political process that both frequently transcends the formal authority of local cities and municipalities and also drives global environmental change, highlighting the importance of scale (Sassen and Dotan, 2011; World Bank, 2010).

Effective urban climate governance is therefore constrained by the fact that the historical and socio-economic factors driving urban resource dependence and vulnerability are often operating at a scale that is well beyond the formal authority of urban authority structures (cf. Sassen and Dotan, 2011). Further complicating the distribution of adaptation and mitigation costs and benefits is the North-South dynamic of global climate politics. Until recently, global climate agreements have required emissions reductions only on the part of northern countries, those belonging to Annex I of the UNFCCC. However, as emerging economies such as China, India, South Africa and Brazil continue to grow, there is now an expectation that rapidly developing non-Annex I countries will make a commitment to future greenhouse gas reductions, and indeed many have made voluntary pledges following the 2009 Copenhagen COP.

Still, despite these complications and limitations, there is little doubt that cities will play a crucial role in this process. According to a report recently published by the McKinsey Global Institute, 40 percent of the world’s 75 “most dynamic” cities are now in China (Dobbs and Remes, 2012: 63).6 In the words of the authors (2012: 63):

China’s urbanization is thundering along at an extraordinary pace; it’s happening at 100 times the scale of the world’s first country to urbanize—Britain—and at 10 times the speed. Over the past decade alone, China’s share of people living in large cities has increased from 36 percent to nearly 50 percent. In 2010, China’s metropolitan regions accounted for 78 percent of its GDP. If current trends hold, the Middle Kingdom’s urban population will expand from approximately 570 million to 925 million in 2025—an increase larger than the entire current population of the United States.

China of course is not alone in this regard. According to the 2011 World Urbanization Prospects, India’s urban population is expected to grow by another 497 million by 2050,7 Nigeria’s by 200 million, Indonesia’s by 92 million and the United States by more than 100 million.

Underlying these transformations are complex processes that have gradually redefined the ways in which land, labor and related resources (e.g., water, fishing, mining rights) are being governed for the purposes of commercial and industrial development (Satterthwaite et al., 2007; Roy, 2009; 2010; 2011; Seto, 2011; Seto et al., 2011; 2012; Sassen and Dotan, 2011). One is a macro-economic shift away from primary production into manufacturing and services (Satterthwaite et al., 2010). A second is a process of global integration whereby urban and peri-urban areas have emerged as important sites of production, processing and exchange (Satterthwaite et al., 2010). A third has been the acquisition and conversion of forests, wetlands, and agricultural land for industrial, commercial and residential development (Roy, 2009; 2010; 2011; Seto et al., 2011).

In many instances, new patterns of land and resource governance have entailed the conversion of areas previously used for agricultural production, creating new forms of vulnerability to climate change (McGranahan et al., 2007; Munslow and O’Dempsey, 2011; McDonald et al., 2011; Adamo, 2010; Romero-Lankao and Dodman, 2011). First, the conversion of forests, water bodies and wetlands for commercial and industrial purposes has affected the ability of urban and surrounding ecosystems to absorb variations in rainfall and discharge, exacerbating vulnerability to flooding (Revi, 2008; Moench, 2010). Second, the loss of agricultural land has undermined local food systems, raising new concerns about urban food security (Satterthwaite et al., 2010; Roy, 2009; 2010; 2011; Seto et al., 2011).8 Third, and related, urbanization has displaced the livelihoods of populations dependent upon hitherto marginal urban and peri-urban spaces, such as wetlands and canals, exacerbating poverty and vulnerability to environmental change (Revi, 2008; Roy, 2009; 2010; 2011; Penz et al., 2011). Fourth, rapid urbanization often undermines the ability of local and national authorities to provide public services in housing, sanitation, water treatment and healthcare, exacerbating vulnerability to water and climate-borne disease (Revi, 2008; Satterthwaite et al., 2010; McDonald et al., 2011: 1). According to another modeling exercise carried out by McDonald et al. (2011), the number of people living with inadequate access to fresh water (defined as less than 1 liter per day) in cities is expected to increase from 150 million to 1 billion people by the year 2050.

The urban climate challenge therefore presents a genuine policy paradox. On one hand, cities are major producers of wealth, productivity and ingenuity that allow us to understand and act upon the factors contributing to anthropogenic climate change (cf. Sassen and Dotan, 2011; Bulkeley and Broto, 2012). On the other, they are major emitters of greenhouse gases, highlighting the fact that the same forces that are driving an accumulation of wealth and prosperity in large urban centers are also often the factors that are creating new forms of poverty and vulnerability to global environmental change.

Understanding the Role of Cities in the Global Climate Regime

Recognizing the challenge of reducing emissions and vulnerability to global climate change highlights a number of conceptual and theoretical themes that have strong bearing on the study of environmental governance regimes. One concerns the challenge of incorporating mitigation and adaptation into urban policy and planning. Recent theoretical work on the ability of cities to mitigate and adapt to climate change has highlighted the importance of developing low-carbon strategies that can reduce the vulnerability of urban populations to climate change (Sassen and Dotan, 2011). The World Bank’s report on Cities and Climate Change (2010), for instance, suggests that urban adaptation and mitigation can be reconciled by adopting an “integrated approach” that “considers mitigation, adaptation and urban development.” Similar...