![]()

1

Introduction

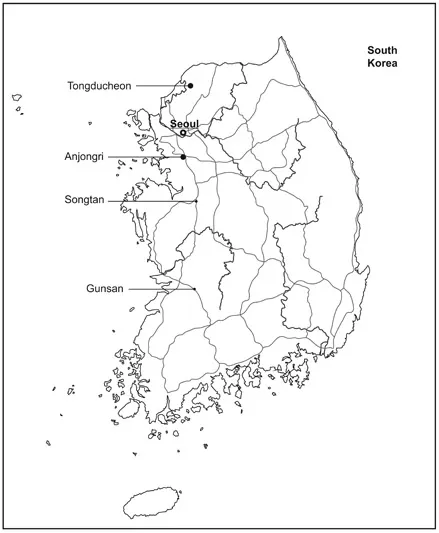

Rosie and I sat at a quiet corner table of a tiny coffee shop in a backstreet of Seoul’s trendy youth district of Hyehwa-dong and chatted about her life and how she had ended up in South Korea. Rosie arrived in 2001 to take up a job as an entertainer in a bar in the town of Tongducheon (known as TDC by the migrant entertainers and US military personnel who live there), which is located on the edge of Camp Casey, the largest US military base in South Korea, forty kilometres south of the North Korean border (see Figure 1.1). Rosie, who was sixteen at the time, had no intention of migrating abroad until she was awoken one evening by a knock on the door of her boarding house in Manila. The woman at the door was a recruiter for an entertainer’s promotion agency. She asked Rosie if she would like to earn a lot of money by working overseas. Rosie was told that everything could be arranged very quickly through the agency. When Rosie showed up at the agency in Santa Cruz, Manila, two days later, she was asked by a Korean woman to strip, put on a see-through negligee and dance (turning around slowly and shaking her hips). Rosie informed the woman that she didn’t know how to ‘slow dance’. Nonetheless, of the thirty or so young women who were at the agency for an audition that day, Rosie was amongst the five chosen to go to Korea. She signed a contract which said she would entertain customers by serving them drinks, sitting with them and chatting. She was also told she would dance on the stage, ‘like a star’. The work appeared to combine dancing with hostessing for a promised wage of USD 450 (KRW 500,000) per month.

In Korea, Rosie was deployed in Y Club. Her Korean boss owned two other clubs in nearby Toka-ri – the infamous M Club and NBC Club. She was sent to M Club to learn how to dance before being transferred to Y Club, where she had a six-month contract to work as an entertainer, renewable for a second period of six months. With the assistance of her American soldier boyfriend Rosie ran away from the club on her fourth attempt to do so. Some of the reasons that Rosie gave for running away from the club meet the United Nations definition of her as a ‘trafficked person’. First, Rosie discovered that hostessing meant much more than dancing, chatting with customers and serving them drinks. Within one week of being at Club Y she was sent to one of the two VIP rooms at the rear of the club for ‘VIP sex’ (ten to fifteen minutes) with a customer. She had to take a condom and a tissue with her whenever she went into one of these rooms. Sex was also performed in the club as ‘short time’ (thirty minutes) and ‘long time’ (six to seven hours overnight upstairs in private rooms). Rosie serviced on average two or three customers this way each night during the three months she was there.

Figure 1.1 Map of the Korean Peninsula showing major US military camp towns

Y Club did indeed have dancing, but not exactly the kind of dancing Rosie was expecting. Nightly strip shows started at 9 p.m, and each woman had a song she would perform to. Each woman was required to strip completely naked before the completion of her song. A woman was required to get on stage when her song began to play, even if she was having sex with a customer at the time – the mama-san would knock on the door to tell her to go to the stage. “We have to run quickly, otherwise we would be punished”, Rosie said. The DJ played the music loud enough to be heard anywhere in the club. Rosie said, “We would get so cold in winter and we would all go to the heater before the customers arrived. But when the mama-san sees this she would turn the heater off and tell us to get up on stage and practice our dancing. Because, you know, none of us knew how to dance when we came to Korea”. The women would usually dance for three hours a night between the hours of 9 p.m. and 12 midnight. On average Rosie said she would get no more than five hours of sleep a night and even less on weekends, when the working hours were 2 p.m. to 5 a.m. At night all the women in Y Club were confined upstairs in their sleeping quarters.

The club instituted a points system to regulate the women’s work. One ‘ladies drink’ (at USD 20) equalled two points. Twenty minutes after the drink was bought the woman had to stand up and ask the customer to buy her another drink or she would move to another table. The mama-san advised:

When you sit with a GI you have to sit on his lap facing him [straddled over his legs] and dance – even before he buys you a drink. If after one minute he doesn’t buy you a drink, you have to go to another customer and do the same thing until a GI buys you a drink.

For each ladies drink sold in a week, the woman would receive KRW 2,000 (USD 1.50), and this money would be given to her every weekend. If a woman earned 200 points (that is, 100 drinks) in a month, she was allowed one day off. Any less and she had no days off.

Rosie did not receive any of her promised USD 450 a month salary in the three months she was in Y Club, only tips from customers and the commission generated through her drink sales. All the salary was supposedly deposited in a bank account of which the mama-san was the signatory, so only the mama-san could sign withdrawal slips. After Rosie ran away and checked the bank account she discovered that only half a month’s salary had ever been deposited into her account and not the USD 1,350 she was expecting.

For Rosie it was the arbitrarily imposed punishments that she and the other women were routinely subjected to that cemented her decision to run away from Y Club. The woman who sold the lowest number of drinks per week was punished by having to do the cooking, cleaning and laundry for all the women for that entire week. This meant getting up at 7 a.m., even if she had worked until 5 a.m. the night before. The week before Rosie ran away she sold the lowest number of drinks and had this punishment imposed. The other form of punishment Rosie described was being locked in a closet with the light switched off for up to half a day. Rosie received this punishment three times in the three months she was at the club. The first time was when the MPs (United States Army Military Police) came to the VIP room, as they routinely undertook inspections of all the clubs near US military bases looking for infringements, including evidence of prostitution involving US military personnel. She was in the VIP room with a customer and an MP asked her what was going on in there. She replied, “This is part of my job. That is why I’m here doing this”. The mama-san was so mad at her for saying it was part of her job that she locked her in the closet for punishment. The closet contained the used condoms and tissues from the women’s sexual encounters, and there was no room to stand up or a bucket to relieve oneself.

A few days after I met Rosie in 2002, she told this same story, as well as other dimensions of her migration experience, to a reporter from Time Magazine (see McIntyre 2002). The story was widely circulated in the United States and Korea, as well as other parts of Asia, and even provoked a reaction from the US government (see Goldman 2002). But because I knew Rosie, I knew what the Time Magazine reporter had omitted from her story as well as what he had chosen to include in the article that was published. McIntyre employed a ‘politics of sex trafficking storytelling’ that requires victims to be presented in a particular way or according to a particular framing of the problem. Much of the information that circulates publicly as knowledge about trafficking into the sex and nightlife entertainment sector produces selective truths that incite some form of political action or, more accurately, reaction. Nicolas Lainez (2010) has elsewhere called this “the victim staged”.

I knew what Rosie had told this reporter, what he had chosen to omit and what I thought were the equally important aspects of her experiences in Korea and in Manila. What was still unknown about Rosie’s experience from McIntyre’s story, for instance, was how exactly she executed her departure from the club and what happened to her afterwards. There was a fifteen-month gap between the time Rosie ran away and her return home to Manila. What had happened to Rosie in the interim period between running away and telling her story to Time Magazine? How had she overcome her experiences in Y Club and attempted to forge a more positive migration experience during this time? How had Rosie, in other words, moved on from her experience of trafficking?

After running away Rosie had in fact gone to the Archdiocesan Pastoral Centre for Filipino Migrants in Seoul (hereafter, the Centre) for advice and assistance. While she was sheltering at the Centre, the staff found her a job at a nearby factory. Rosie worked six days a week, twelve hours a day for a year at the factory as an undocumented migrant. During this time she kept in contact with her American soldier boyfriend, who had assisted her in running away from the club. After a year she decided to return to Manila because she was tired of having to remit all her monthly salary each month to pay for her mother’s expenses and medical costs. Remitting all her salary from the factory meant she had to continue to rely on her boyfriend in Korea for money for her own living costs. Once back in Manila Rosie returned to the impoverished squatter district of Tondo where she lived with her mother and two younger siblings. She soon met and fell in love with a Filipino man to whom she became pregnant. They planned to marry and rent a house together not far from Rosie’s mother in Tondo, but her mother had other ideas. After she returned to Manila, Rosie’s American soldier boyfriend regularly sent her money. Rosie’s mother was hopeful that this American boyfriend would eventually marry Rosie, so she sent her back to Korea to become engaged. Rosie was naturally reluctant to go given her new romance in Tondo. When she arrived at the apartment in TDC that her ex-boyfriend had rented for her and revealed that she was three months pregnant with another man’s child, he tried to strangle her. Although she was badly beaten, Rosie managed to kick him and run from the apartment without her clothes, passport or any money. She made her way back to the Centre for a second time and sought their assistance to recover her passport so she could go home. Although Rosie told this story to the Time Magazine reporter he decided not to include this information because, as he later told me, it diluted Rosie’s positioning as a “pure victim” and was thus not in the best interests of the story. Now pregnant at eighteen years of age, unmarried, subject to abuse by a former American boyfriend, employed as an irregular migrant worker in a factory in Seoul … these were, I was told by the reporter at the time of the story’s publication, unnecessary complications to an unambiguous story of sex slavery involving a minor.

Two years after Rosie first migrated to Korea as an entertainer she returned to Manila to marry her Filipino boyfriend and have her baby. She resumed her life as a survivor of trafficking in ways I had never seen reference to in the burgeoning literature on human trafficking, where victims are commonly understood to be in need of rescuing, rehabilitating in shelters and subsequently reintegrating into their home communities, or in ways that were reflected in Time Magazine’s reporting of Rosie’s story. This disjuncture between the ‘victim staged’, which privileges a particular discourse of sexual servitude, and the lived experience of trafficking and post-trafficking for women like Rosie, with its silences, absences and anxieties, forms the basis of this book.

Points of contention: trafficking, post-trafficking and moving on

This book has two aims. The first is to examine exactly how some migrant Filipinas who come to South Korea on entertainer’s visas are ‘trafficked’. In the context of current academic literature on human trafficking understanding exactly how a group of migrant women is trafficked is a contentious exercise because of an increasingly influential body of scholarship eschewing a trafficking framework in interpreting women’s experiences of marginal migration into the sex and nightlife entertainment sectors. To elaborate, we might divide human trafficking research into two broad categories: those which attempt to document the experience of sex trafficking, as in the Time Magazine story, and those which attempt to refute claims of trafficking through alternative interpretations of women’s experiences of vulnerable migration and precarious work in the sex and nightlife entertainment sectors. The latter studies make various arguments to the effect that a trafficking framework is not useful in interpreting women’s experiences because the women concerned knowingly and willing participate in pub and bar work, including where they perform sexual labour, and because current anti-trafficking interventions often act to further marginalise women and compromise their human and labour rights. Thus, even though women may operate under “constrained choices” (Sandy 2007) when they agree to migrate for sexual and erotic labour, they nonetheless exercise agency in their migration and work decisions. This argument has been made in relation to many groups of migrant sexual labourers and specifically in relation to Filipina migrant entertainers in Japan (Parrenas 2011) and in Korea (Cheng 2010).

Yet in reflecting on the experiences of women like Rosie in TDC it seems clear that trafficking does supply an important frame for understanding these Filipinas’ employment situations. And it is here that the ‘either/or’ dyad of sex trafficked or not trafficked is ultimately unhelpful in understanding experiences of women like Rosie and why I wish to advance a different trafficking interpretation of these women’s experiences in this book. My argument is that women like Rosie are trafficked but that their trafficking experience cannot be reduced to the types of sensationalist platitudes or superficial interpretations supplied in media accounts of sexual servitude or ‘thin’ research which emphasises extreme sexual exploitation as the key site through which their trafficking emerges. The opening vignette describing Rosie’s experiences illustrates that sexual exploitation is one element of a broader pattern of exploitative practices and labour relations in Club Y and that it was labour issues – non-payment of salary, arbitrary deductions and fines, humiliation and physical punishment and so on – that Rosie chose to emphasise in recounting her situation both to me and to the Times Magazine reporter. Rosie had three GI boyfriends and strategically deployed her sexuality and sexual intimacy to recover and advance her own goals in migration, so I find it difficult to endorse any suggestion that she was a ‘sex slave’ or victim of sex trafficking, even if she may have preferred a job where sexual labour was absent or less starkly performed. As I will demonstrate in this book, ‘labour exploitation’ more accurately describes the most significant realm through which women understand themselves as exploited and bonded labourers in Korea. Adopting such an understanding has implications for the ways we view various aspects of exploitative situations in gijich’on (lit. US military camp towns, in Korean) pubs and other sites where sex trafficking is supposedly rife.

The second aim of the book is to explore the trajectories of migrant Filipina entertainers after they leave the clubs to which they are deployed in Korea. I examine how vulnerable and exploited migrants like Rosie manoeuvre and work towards overcoming situations of marginality and exploitation in their migration through their own agentic expressions that emerge outside responses to them as sex trafficking victims. How, in other words, do women like Rosie enact trans-national possibilities of ‘moving on’ in ways that sit almost entirely outside a framework of anti-trafficking interventions? Despite a growing body of research on the migration of Filipinas as entertainers very little attention has focused on post-club lives of women, especially where they remain in the migrant destination, often as undocumented or irregular migrants. Despite their book-length treatment of the personal and working lives of Filipina entertainers in Korea and Japan respectively, neither Cheng (2010) nor Parrenas (2011) give more than passing treatment to post-club manoeuvrings of women who run away from the clubs and remain in the migration destination, with Cheng focusing principally on what happens to women only after they return home to the Philippines. Lieba Faier’s (2008) study of Filipina wives in rural Japan is an important exception to this omission in its ethnographic treatment of former Filipina migrant entertainers who marry Japanese men – often ex-customers in the bars where they previously worked – and remain as wives in Japan. Following Faier, I also found that women’s post-club lives are fraught with the challenges of breaking away from the club and the stigma attached to club work. In their romances, in other types of work and in relations with ‘home’ in the Philippines, as well as with service providers and support workers for exploited migrants, these women must continually negotiate, manoeuvre and resist the impositions of the club. This book focuses on the lives of women who run away and remain in Korea.

Points of contact: methodology

The silences and absences in the re-telling of Rosie’s and other women’s experiences are replicated in the vast majority of accounts of trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation.1 Many researchers who study human trafficking interview victims in shelters or rehabilitation facilities because these places provide a convenient source of potential research participants. This has led Brunovskis and Surtees (2010) to identify the problems with current approaches to research with women trafficked into sex industries globally as “selection effects”, where biases in who gets to tell their story, how and in what context (usually a shelter) result in narratives of many trafficked persons outside this narrow purview remaining untold. The overwhelming majority of accounts of any form of trafficking – by researchers, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and the media – are indeed based on a small number of identified and assisted victims, located predominantly within and through NGOs and shelters. This bias reflects one of the key issues facing researchers in this field – namely, the difficulty of finding and then accessing “hidden populations” of trafficked people (Laczko 2005). Researchers either access victims’ accounts first-hand from the women who use the services of NGOs (for example, Crawford 2010) or they interview NGO staff and obtain selectively drawn accounts based on NGO records (for example, Samarasinghe 2008). When researchers do manage to meet trafficked persons the line of questioning often pertains to a narrow range of topics, such as how many men the victim was forced to have sex with, if she was deprived of food and/or freedom, if she was abused and so on. This line of questioning, which also appears in media accounts like the Time Magazine story mentioned earlier, reveals only absences and reinforces only stereotypes of what is known and what is expected to be known about the ‘global problem of sex trafficking’.

Apart from selective and partial encounters between researchers or media and trafficked persons, much existing research on human trafficking does not actually aim to include the voices of trafficked persons. As Long (2004: 8) l...