![]()

Part I

Examining non-timber forest product systems

![]()

The need to understand the ecological sustainability of non-timber forest products harvesting systems

Charlie M. Shackleton, Tamara Ticktin and Ashok K. Pandey

Introduction

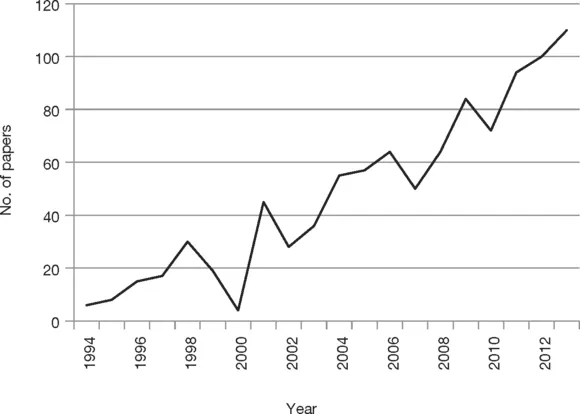

The importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) in rural livelihoods in developing countries has become widely acknowledged over the last decade or so within the research and, increasingly, policy arenas, on the basis of numerous studies from around the world. Indeed, there has been a tenfold increase in the annual number of research papers published over the last 20 years (Figure 1.1). Most of these studies are from developing countries, but they do include developed countries (e.g. Kim et al. 2012, Poe et al. 2013, Sténs and Sandström 2013). Additionally, most are from rural areas, albeit with a smattering from urban settings (e.g. Kilchling et al. 2009, Poe et al. 2013, Kaoma and Shackleton 2014), although with increasing urbanization this distinction is blurred with significant markets for rural NTFPs imported into towns and cities (Lewis 2008, Padoch et al. 2008, McMullin et al. 2012). Two pertinent findings of many of these studies is that NTFPs generally contribute in many different ways to local livelihoods (see Chapter 2) and that when translated into income terms many households earn a significant proportion of their income (cash and/or non-cash) from NTFPs (Shackleton et al. 2007, Angelsen et al. 2014). In other words, they are not simply minor products of little value, but rather they are vital components of livelihoods, and in some instances, of local and regional economies. This requires that they, and the land on which they are found, are managed in a responsible manner to ensure that these livelihood benefits continue to accrue to rural, and often impoverished, people.

Figure 1.1 The increase in research publications on NTFPs over the last two decades (the data reflect the number of papers returned by Scopus to a single search on the term ‘non timber forest products’ in all search fields)

Despite the importance of NTFPs in the livelihoods of rural communities, government agencies in most countries place considerable restrictions on which NTFPs can be harvested and in which quantities. This is interpreted as being a result of one or more of the following three reasons:

• The legacy of colonial restrictions and central government controls during much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Vandergeest and Peluso 2006a and 2006b, McLain and Lawry Chapter 15). While there has been a growing move towards devolution of forest ownership and governance over the last decade or two (Ambus and Hoberg 2011, Lawry et al. 2012), restrictive policies on the use of biodiversity continue to linger as an echo of the previous century of prohibitions and control (Ribot et al. 2006, Conkleton et al. 2012).

• Countering the calls for increased devolution of control and management of forests and NTFPs to indigenous peoples are the widely publicized concerns related to global biodiversity loss. Whilst such loss is a result of multiple causes (Krauss et al. 2010, Visconti et al. 2011), governments and authorities use this as an argument to limit harvesting of biodiversity resources, unless regulated by them. Such regulation is frequently associated with revenue streams for the authorities (Ribot et al. 2006).

• There are relatively few studies on the approaches to and impacts of harvesting and guidelines for promoting ecological sustainability. Consequently, many authorities adopt a precautionary approach rather than an adaptive one (Alexander and McLain 2001, Shackleton et al. 2009). The absence of clear guidelines is largely a result of the daunting multitude of NTFP species for which in-depth studies are required (Ticktin and Shackleton 2011). Moreover, this challenge is magnified by the need to further understand how harvesting impacts and responses differ in different locations and contexts even for the same species (Gaoue and Ticktin 2010). Consequently, management of most NTFPs is based on limited and frequently untested western scientific assumptions and knowledge of the species autecology and its response to harvesting. Whilst there is undoubtedly an immense wealth of local ecological knowledge about NTFP species and their responses to various factors (e.g. Gaoue and Ticktin 2009, Youn 2009), including harvesting, very little of this has been codified and is therefore frequently overlooked by most formal forest or conservation management authorities (Love and Jones 2001), although there are exceptions (e.g. Shanley and Stockdale 2008, Rist et al. 2010).

The combined consequence of these three positions is that many conservation and forestry management authorities view the harvesting of wild resources as contrary to the health of the species and ecosystems in which they occur (Nygren 2004, Rist et al. 2010). They typically view harvesting as an activity destructive of the individual, the species and, over the long term, the ecosystem. Thus, they are loath to permit access to lands and resources under their care for the harvesting of NTFPs (Wilshusen et al. 2002, Shackleton et al. 2009, Rist et al. 2010).

This stereotypical view of the assumed inevitable negative effects of harvesting can be countered at a number of levels. The first is that it ignores that all ecosystems on earth have been impacted by human actions over millennia, i.e. humans are part of nature, not external to it. Humans have inhabited, transferred species into, burned, harvested and herded livestock over all ecosystems to a greater or lesser degree, even those deemed as pristine or the last remnants of untouched nature (Fairhead and Leach 1995, Tipping et al. 1999, Barlow et al. 2012). Second, additional to these anthropogenic effects shaping community structure and composition over thousands of years is the current reality of global climate change which is altering species growth rates, competition and relative performance and hence the composition of biological communities and ecosystems even in sparsely inhabited regions (e.g. Foden et al. 2007, Huber et al. 2007), which further emphasises that no systems are immune from human impacts. Thirdly, it assumes that ecosystems, species distributions and the relative dominance or presence of individual populations are relatively static, as well as the social context in which they are used or not. Yet, it is now well appreciated that all ecosystems are dynamic, in constant change, which alters the relative ratios of species to one another in time and space and hence and their contributions to ecosystem dynamics (Garmestani et al. 2009). All ecosystems are also subjected, to some degree, to multiple external shocks and stresses such as fires, tornados, earthquakes, pest outbreaks and droughts which have devastating and long-lasting effects on species composition and community structure (Scheffer et al. 2001). Thus, focusing on the prevention of NTFP harvesting as a means to limit change or potentially negative impacts to populations or species ignores all the other pressures and changes that populations and ecosystems are exposed to, some human mediated, some not, and with sometimes detrimental impacts whilst at other times positive ones. The last, which is the subject of this book, is that not all harvesting results in negative consequences for the species or systems concerned. Just because humans extract NTFPs does not mean that the harvested NTFP population is doomed to extinction, and if widely enough, the species will follow suit. Rather, there is a wide range of species responses to harvesting, which are mediated by the local context, from stimulation, to tolerance, to decline (Ticktin and Shackleton 2011). The trick is therefore, rather than viewing all harvesting as inevitably negative, to understand which species (or functional traits), which harvesting regimens and which contexts are likely to result in negative impacts on NTFP populations and species, and in which situations such negative outcomes are unlikely.

Negative narratives ‘seem’ to be a lot more common than positive ones. Is this true and why might it be so? Verifying whether it is true is a nigh impossible task. However, one of several catalysts for compiling this book was, what appeared to us to be, increasing incidences of postgraduate theses advocating prescriptions against NTFP use even when contradicted by their own empirical findings. As is common for most research academics each of the editors has been invited from time to time by universities around the world to examine theses written by masters or Ph.D. students. We have been struck by instances where postgraduate students have presented data showing that the harvesting of a specific NTFP, or suite of NTFPs, in a defined location appeared to be sustainable on the basis of the data and empirical results presented in the thesis, and yet in the final conclusion to the thesis, they advocate that harvesting should be limited. They have seemingly been ‘indoctrinated’ to view all harvesting as detrimental. We have also had some of our own postgraduates do the same in early drafts of their theses. In a slight variation on this, we have encountered instances where some postgraduate theses conclude that the harvesting appears sustainable, but then they add a caveat to the effect that restrictions are nevertheless required because offtake will become unsustainable at some unspecified time in the future in the face of growing human populations in the area and/or increasing commercialization of the resource (which often they have not verified). However, this assumes that local communities or harvesters are unaware of any changes in resource supply and have no agency with respect to their own livelihoods, both of which can be questioned. It also assumes that per capita demand will remain static even in the face of external social and economic influences such as increased rural–urban migration and increased access to markets for modern goods and products, technology, information, government support services and infrastructure, all of which increasingly influence livelihoods and their income sources (and amounts) in even relatively remote communities. Lastly, in the face of rapid urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia even the assumed population increase in rural villages is not ubiquitous across all sites as individuals and households leave in hope of better prospects in the towns and cities. Thus, the assumed population growth and/or commercialization may not actually occur, and even if it does, it may not be as soon as is assumed, and even then it might not translate to increased demand as consumer preferences change. Therefore, it is not a foregone conclusion that it will increase the demand for all NTFPs. We fully appreciate that there is no malintent in portraying the final conclusions in such a way even against their own empirical findings. But with inexperience they are less willing to confront a dominant narrative arguing pervasive unsustainability. Many instances of overharvesting can be found, but it is not an inevitable outcome of NTFP harvesting (as this book will show). Consequently, we would encourage a more critical, nuanced, context-specific and evidence-based examination of the species, its responses and the socioeconomic context and drivers at appropriate and defined spatial and temporal scales.

This begs the question of why the negative narrative is so pervasive. Is it because most NTFP harvest systems are indeed unsustainable, or perhaps there is an unconscious bias by researchers to examine mostly unsustainable systems because that allows them to motivate for research funds and provide management recommendations (i.e. why study a system that appears fine and in no need of intervention)? We are unsure, but can identify a few possible hypotheses which require greater examination:

• It reflects the situation on the ground. This may be because:

– More areas and NTFPs are being harvested unsustainably because of changing conditions and demands.

– Greater scientific interest is revealing something that has always been extant but overlooked.

– Increased land transformation which results in people having to harvest from an ever-decreasing area of land.

– Increasing commercialization and supplies to urban populations and markets.

– Some combination of two or more of the above.

• It does not reflect the situation of the ground but it is perpetuated as a stereotypical narrative co...