eBook - ePub

The Capitalist Space Economy

Geographical Analysis after Ricardo, Marx and Sraffa

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Capitalist Space Economy

Geographical Analysis after Ricardo, Marx and Sraffa

About this book

Representing an innovative approach to the analysis of the economic geography of capitalism, this stimulating book develops an analytical political economic framework. Part 1 provides an introductory overvi9ew fo some of the fundamental debates about price, profits and value in economics which underlie the analytical political economy approach. Part 2 analyzes the special role of space and transportation in commodity production and the spatial organization of the economy that this implies. Parts 3 and 4 examine the conflicting goals and actions of different social clases and individuals and how these are complicated by space, concluding with a detailed analysis of capitalists' strategiesas they cope with uncertainty and disequilibrium.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Capitalist Space Economy by Eric Sheppard,Trevor Barnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Introduction

During the last fifteen years there have been some significant changes within economic geography. In the mid-1970s theoretical discussion within the discipline was dominated by ideas taken from mainstream, neoclassical economics. Certainly, there was an underground movement critical of that orthodoxy (Harvey, 1973; Massey, 1973; Sayer, 1976), but these attacks generated as much heat as light, and provided little in the way of a positive alternative theoretical framework. Since then, however, there has been a concerted attempt by a number of economic geographers to construct just such an alternative based on ideas of political economy. Furthermore, this approach has quickly achieved recognition, and now provides a coherent explanatory thesis that is taken at least as seriously as any other in economic geography.1

Writing within the spirit of this recent movement, our book is intended to explicate, clarify and extend the conceptual foundations of the political economic paradigm within economic geography. It is therefore a book about ideas and beliefs, an attempt to present the conceptual skeleton that underlies any political economic approach to economic geography, rather than a presentation of empirical research. None the less, it is a conceptual skeleton that can be fleshed out by existing case studies (which we point to throughout the book), and also can point to fruitful directions for further empirical work.

As a model for the kind of account we wish to present, we pay homage to David Harvey’s (1982) Limits to Capital, from which we drew many insights and ideas. Yet our argument is different in style from his, and indeed from many others whose ideas we share. For at the core of this book is the belief that a clear account of the political economic approach is obtained by interrogating our subject matter with an analytical (mathematical) logic. We argue that this serves four closely interrelated purposes.

First, the adoption of an analytical language enables us to present a sustained critique of the dominant rival paradigm, neoclassical economic geography. In the rhetoric of debate, adherents of neoclassical ideas tend to dismiss their political economic critics on the basis that they are ‘unscientific’, ‘woolly’, or ‘biased’, irrespective of the (usually considerable) substantive merit of the opposing arguments. By harnessing an analytical logic in the service of political economy, we argue that a coherent and damaging critique of neoclassical theory, and the beliefs it propagates in economic geography, can be sustained. As such, the use of analytical methods provides the possibility of an ‘internal critique’ of neoclassical economic geography – internal in the sense that the criticism is framed in the same language and mode of thought as the position criticized (Chapters 2 and 5).

Second, by subjecting the claims of political economic theorists (both geographers and non-geographers) to this same analytical examination, we can logically separate sustainable ideas and concepts from those that are inconsistent and contradictory. From this analytical sieve we then provide a systematic and internally consistent account of the capitalist space economy from a political economic perspective (Chapters 3, 4 and 6).

Third, by introducing space and place into the very centre of this analytical account, we argue that a number of central theoretical claims made by previous writers in economic theory must be at least qualified if not rejected (Chapters 4, 6, 10, 11 and 13). In this sense our conclusion echoes that of Harvey’s (1986, p. 142), who writes that ‘the incorporation of space has a numbing effect upon the central propositions of any corpus of social theory’.

Finally, the analytical framework enables us to address a number of pedagogical tasks within the book: to provide an introduction to the paradigm of political economy for those students unfamiliar with the approach, but who have the patience to follow a deductive argument; to construct a wide-ranging model of the capitalist space economy incorporating commodity production, natural resources, the built environment, class formation, technical change and industrial organization; to show radical scholars how their work fits with others; to demonstrate to non-geographers how space is integral to political economy; and, finally, to cajole neoclassical adherents into thinking more critically about their own approach – and more favourably about our own!

As a preface to our substantive arguments and analysis, in this introductory chapter we present, first, a historical overview of the rise, fall and rise again of political economy in economics; second, a discussion of the leading variants of contemporary analytical political economy; third, a review of the book’s method in light of this analytical turn; and, finally, a synopsis of the book’s structure and argument.

1.1 From political economy to neoclassicism and back

In this section we discuss the emergence of political economy in the first part of the nineteenth century, the very different nature of neoclassical economics that followed it, and the subsequent revival of interest in a revamped analytical political economy during the last twenty-five years. Our characterizations are of necessity brief, and more systematic accounts of the issues and debates we allude to in this section are taken up in Chapters 2 and 3. In this chapter we simply wish to establish the intellectual and historical context of the political economic approach that we will pursue in the remainder of the book.

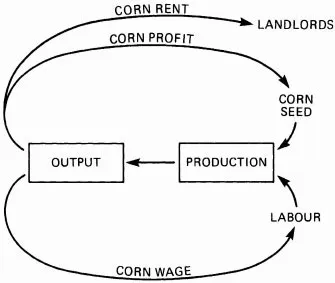

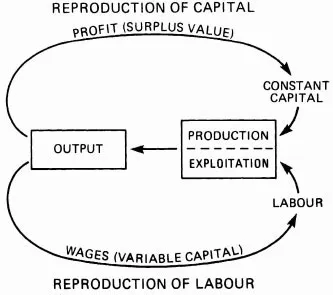

The political economic approach is primarily associated with the classical economists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and, in particular, with the writings of David Ricardo and Karl Marx. Central to both Ricardo’s and Marx’s schemes were issues of first, value, that is, the fundamental determinants of relative prices; second, production and reproduction; and third, the distribution of income among social classes. The similarities and differences between Ricardo and Marx are seen in Figures 1.1 and 1.2, respectively.

Figure 1.1 Ricardo’s corn model

Figure 1.2 Marx’s model

Ricardo did not have a consistent value theory. In his later work he employed some kind of labour theory of value where prices of goods are determined by the amount of labour time embodied in their production (the 93 per cent labour theory of value, as Stigler called it), while in his earlier writings he used a so-called corn theory of value. In each case, though, value is created in the process of production. In fact, Ricardo went to considerable lengths in his work to avoid discussing non-produced goods, which, by definition, are peripheral to his value theory. Specifically, in order not to complicate his analysis with scarce, non-produced goods Ricardo used an analytical trick. He eliminated non-produced goods by assuming that the prices of commodities produced on, say, the non-produced commodity land are set only by the price of production on the marginal plot. The crucial point is that the marginal land is not scarce, reflected in the fact that it pays no rent. Of course, intramarginal lands pay rent, but such rents do not affect the price of produced goods grown on them (Pasinetti, 1981, ch. 1). By setting scarcity and non-produced goods aside in this way, Ricardo was able to ‘carry on his inquiry into the commodities which he really wanted to investigate – the produced commodities’ (Pasinetti, 1981, p. 7).

Although Ricardo focused on produced goods, one of his major contributions to nineteenth-century political debate was in making an argument about the owners of non-produced goods, namely, the landlords. In particular, Ricardo argued that in the sphere of distribution landlords represent an obstacle to the reproduction of produced goods, and thereby the creation of value. This is best illustrated by Ricardo’s corn model (Figure 1.1). In this one-commodity world, capital (which is made up only of corn seed), labour and land are combined to produce the output corn. From the total output of corn, part goes towards wages, while part goes towards profits. In turn, part of that profit is invested in the form of seed to reproduce corn in the future, while part is paid as rent to landlords owning intramarginal lands. With wages set at some ‘natural’ level, the central distributional conflict is then between landlords and capitalists. What landlords capture as rent, capitalists necessarily lose in profits. Ricardo’s point is that, while capitalists perform the ‘useful’ function of reinvesting their profit, thereby permitting reproduction of the economy, the landlords are a fetter on accumulation because they only consume. This was an important contribution to debates surrounding the rising importance of capitalists and the resistance of the important landowning class during the onset of industrial capitalism in Britain.

Sixty years later when Marx was writing, history had turned a corner and the central conflict was no longer between landlords and capitalists but between capitalists and workers. In emphasizing this new antagonism on the factory floor, Marx moved away from a ‘naturally’ defined measure of value such as corn (with which Ricardo flirted), and anchored it unambiguously in the sweat of the labourer’s brow. Specifically, commodity prices are determined by the socially necessary labour time contained within them, where ‘socially necessary’ means the labour time required to produce a good using the average, median or modal technique of production at any given historical moment (for further discussion see section 3.3.1). Although landlords are certainly still important for Marx, they play a negligible role in the core of his scheme (Figure 1.2). None the less, Marx’s scheme still bears a close relationship to Ricardo’s earlier corn model. Specifically, for Marx combining capital and labour (termed by him constant and variable capital) enables production to occur, resulting in a given level of output. Part of that produced output goes to capitalists as profit (surplus value) and is then reinvested, enabling the reproduction of constant capital. The remainder goes to workers in the form of wages, enabling the social reproduction of labour. It is the so-called rate of exploitation at the workplace that settles the division of the output between wages and profits. Exploitation is formally defined in Chapter 3, but the gist of the idea is that it occurs when the worker produces more value during a day than s/he is paid in wages for that same period.

From these admittedly crude and brief portrayals, the hallmarks of political economic perspective are a concern with value, production and reproduction, and distribution. Of these it is distribution that accounts for the ‘political’ part of political economy, because within Marx’s and Ricardo’s frameworks it is this issue that pushed their enquiry beyond the realm of the purely economic, and into the sphere of social and political analysis. For Marx, distribution meant examining questions of property ownership and political power expressed in terms of exploitation; while for Ricardo it meant examining the political power relationships between an embryonic class, the capitalists, and a historically entrenched one, the landlords. Finally, we should also note that neither Marx nor Ricardo presented their work in formal mathematical terms (admittedly Marx made use of some algebra and numerical examples, but in general his forays into mathematics were not successful – witness his difficulties in providing a consistent analytical solution to the problem of transforming labour values into prices; see Steedman, 1977). This does not mean, though, that Ricardo and Marx were against mathematics, or that their work cannot be expressed in mathematical terms. Joan Robinson (1964) argues that Ricardo’s work represents the first abstract economic model ever constructed, one portraying causal relationships between dependent and independent variables (see Gudeman, 1986, ch. 3), while Lafargue attributes to Marx the statement that ‘a science becomes developed only when it has reached the point where it can make use of mathematics’ (Smolinski, 1973, p. 1201).

The neoclassical economics that subsequently arose in the 1870s is a misnomer, for very few of the concerns of the classical economists were retained. In fact, in many ways neoclassical economics represents a rejection of political economy. Neoclassical value theory thus begins not with produced goods and their conditions of production and reproduction, but with scarce non-produced goods and their conditions of exchange (Figure 1.3). In particular, the neoclassical general equilibrium model presumes the existence of a set of rational individuals who are endowed with a given allocation of natural resources. These individuals own such resources, and possess well-defined utility preferences; that is, they know what they like and dislike and can judge the satisfaction from making a given choice. The economic problem is then to find ‘those prices (equilibrium prices) which bring about, through exchange, an optimum allocation of these given resources; this optimum allocation being defined as that situation at which the individuals maximize their utilities, relative to the original distribution of resources among them’ (Pasinetti, 1981, p. 9). In short, the economic problem is one of rational choice. Prov...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- Preface and acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- PART II THE PROFIT-MAXIMIZING SPACE ECONOMY

- PART III DISEQUILIBRIUM: CLASS CONTRADICTION AND STRUGGLE

- PART IV DISEQUILIBRIUM: TECHNICAL CHANGE AND ORGANIZATION

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index