eBook - ePub

Advances in School Psychology (Psychology Revivals)

Volume 8

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advances in School Psychology (Psychology Revivals)

Volume 8

About this book

Originally published in 1992, this title is the last in a series of books on school psychology. It contains diverse contributions relevant to school psychology, research, theory and practice at the time. Including chapters on alternative intervention strategies for the treatment of communication disorders, strategies for developing a preventive intervention for high-risk transfer children, a review of sociometry and temperament research, a review of the recent advances in research in training behavioral consultants at the time, and an overview of school-based consultation to support students with severe behavior problems in integrated education programs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Advances in School Psychology (Psychology Revivals) by Thomas R. Kratochwill, Stephen N. Elliott, Maribeth Gettinger, Thomas R. Kratochwill,Stephen N. Elliott,Maribeth Gettinger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Alternative Intervention Strategies for the Treatment of Communication Disorders in Young Children with Developmental Disabilities

Ann P. Kaiser

Mary Louise Hemmeter

Cathy L. Alpert

Vanderbilt University

Mary Louise Hemmeter

Cathy L. Alpert

Vanderbilt University

By the time a normally developing child reaches the age of 12, his/her vocabulary may exceed 50,000 words. More importantly, as a relatively competent speaker and listener, the typical 12-year-old will be able to understand almost all of what is said to him/her and to describe most experiences using a complex syntactical system that maps causal and logical relationships, marks the relative importance of various ideas, and combines words to multiply the number of meanings that can be expressed using vocabulary alone. The 12-year-old also will be able to communicate according to an elaborate set of pragmatic rules on the basis of his/her metalinguistic skills. In using productive verbal skills, he/she will access rule-based knowledge related to phonological production, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics simultaneously and make a myriad of small adjustments based on the conditional rules that modify each of these systems separately and in relationship to one another. To communicate fluently requires auditory and perceptual processing, phonological production, semantic and episodic memory, and the capacity to respond to multiple, transitory, complex social and linguistic stimuli within milliseconds.

The language and communication skills the typical 12-year-old exhibits represent a specific human capacity that is unequaled. Human society is defined, both literally and metaphorically, by the social linguistic communication. Whether one ascribes to a linguistic determinism view of culture (Whorf, 1956) or simply regards language in its written and oral forms as the primary means of communication within the culture, the critical role of communication skills in human transactions is readily apparent.

Even more impressive than the taxonomy of skills related to the performance of complex social verbal communication is the rapidity and ease with which most children acquire these skills. By the end of their third year of life, children have mastered the essentials of complex communication. Although expansions of vocabulary and refinements of syntax and pragmatics will continue throughout the preschool and primary school years, 3-year-olds are surprisingly competent communicators having already mastered a vocabulary of 1,000 words, most of the phonological system, enough of the morphological and syntactic systems to communicate primary social meaning and many causal and attributional meanings. All this is accomplished without formal instruction. Apparently, the social function of language in the context of everyday conversational interaction is sufficiently motivating for the normally developing child to learn the critical skills needed for mastering the basic forms and functions of the communication system.

Many children have difficulty acquiring one or more aspects of the communication system. In 1988, approximately 1,114,410 school-aged children were diagnosed as speech and language impaired (Annual Report to Congress, 1988). This figure, although representing the largest single area of services within special education, probably underestimates the occurrence and treatment of speech and language related problems in the school context. A diagnosis of language impairment in the early grades is frequently replaced with a diagnosis of learning disabilities in later grades. While difficulties in acquiring communication may be the singular disability of concern in school based intervention, such difficulties may also be one of a cluster of related skill deficits included in learning disabilities or mental retardation and not specifically labeled or treated in children in later grades.

Acquisition of adequate communications skills is essential to the social and academic functioning of school-aged children. In the early childhood years, concern is focused on the acquisition of language and communication skills as a critical developmental milestone. Serious delays in acquiring these skills may subsequently impact older students' ability to learn in the school instructional context. Language learning difficulties frequently carry over to difficulties in learning to read (Maxwell & Wallach, 1984). For students beyond the 3rd grade, both independent acquisition of new knowledge through reading and limitations in their verbal abilities may further reduce their competence and/or performance in academic content areas. In addition, communication deficits directly impact children's relationships with peers and sometimes their ability to relate to adults within and outside the school setting (Brinton & Fujiki, 1989). In summary, the development of communication skills is a keystone to children's academic and social development and thus, effective, early intervention to remediate language deficits is a critical issue for school psychologists, teachers, speech and language therapists and for parents.

This chapter is organized into six major sections. We begin by describing the components of the language and communication system; next, the nature of language disorders is discussed. These discussions are intended to provide the reader with background for the discussion of current views of language learning, models of intervention and examples of their application which are covered in the subsequent three sections. The conclusion offers a brief summary of the current issues in research and practice related to treating communication disorders.

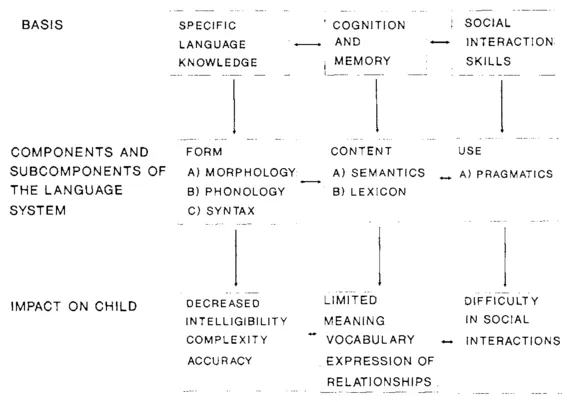

Components of the Language System

Language is a rule-based system for social communication that relies on cognition, social interaction, and the use of a linguistic symbol system to express meanings. Language has both receptive and productive aspects that depend on separate but related capabilities for encoding and decoding linguistically mapped social meanings. Spoken language can be described in terms of six major components: phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, lexicon, and pragmatics. These components comprise the form of language (phonology, morphology, and syntax), its content or meaning (lexicon, semantics) and its use (pragmatics). In this chapter, we are largely concerned with spoken language rather than signed or written language. Thus, the components of the language system are defined in terms of spoken language and important exceptions for signed and written language are noted as such.

Phonology is the rule-based system for the production of the sounds of a particular language. Phones are the actual sounds produced by the speaker; phonemes are classes of sounds that are related, yet perceptually distinct as a result of their production characteristics. The sounds produced by the speaker can be distinguished on the basis of their place and manner of production. In English, there are about 45 phonemes; 21 are classified as vowels and 24 as consonants. Speech production is a complex and dynamic process requiring fine motor control of the lips, mouth, tongue and breath as well as their coordinated use to change the shape of the vocal tract. The acoustic signals that are produced as a result of air passing through the vocal tract are perceived as speech sounds (Owens, 1988).

Difficulty in articulating the sounds needed for spoken language can result from delays in motor development, malformations of the oral-peripheral mechanism (for example, a clef palate), or from specific brain damage incurred at any point in the life span. Deficits in articulation skill are not necessarily related to other language learning abilities or to overall cognitive development. Children who experience delays in articulation may develop normally in terms of cognitive skills and use of language in social interaction. Furthermore, children with great difficulty in producing spoken language may have highly developed receptive skills that allow them to comprehend and learn complex language. Use of alternative modes for production, such as signs or computer-based voice synthesizers, can provide a production mode for children whose motor abilities will not support the development of spoken language.

Morphology and syntax are related rule systems governing the combination of units of meaning within words and within sentences, respectively. Morphemes are the smallest unit of meaning. Free morphemes are words; bound morphemes are markers added to words to modify their meaning. In English, plurality [-s], possession [-s'|. past tense [-ed], and manner [-ly;-er] may be marked morphologically. In addition, entire word meanings may be changed by the addition of prefixes [e.g., un-, in-, pre-] or suffixes [e.g., -ness, -ment]. The complexity of meanings and rules related to morphological use varies and thus, some morphological conventions are acquired earlier in language development than others.

Syntactical rules provide a hierarchical structure that is the basis for sentence organization. Syntax includes word order rules, sentence organization rules, and rules governing the formation and use of word classes within sentences. Children initially learn a limited set of rules that allow them to produce simple sentences, possibly without full knowledge of the constraints that apply to word order and usage. Early word combination production may be based more on children's expression of relational meaning than in their understanding of the rules governing sentence production (Bowerman, 1976). By the age of 36 months, children show evidence of understanding many of the rules for generating simple sentence forms that resemble adult sentences. From this point through adulthood, language learners continue to acquire increasingly complex rules for generating and understanding meaning in sentences. By age 12, children have acquired an extremely complex set of rules that allows expression of complex causal, relational, and logical meanings in a variety of ways.

The development and productive use of morphological and syntactic systems usually are linked to cognitive development. However, the particular difficulties of learning the language system sometimes result in language delays that exceed the child's cognitive delay. When children do not have full access to auditory input, as in the case of hearing-impaired children, or to the full range of social and environmental stimuli associated with linguistic interaction, as may be the case with children living in impoverished environments, rule-based language development may be delayed even when nonlinguistically based cognitive skills are developing normally. While language deficits almost always are associated with mental retardation, the type and degree of delay vary widely even within groups of children having the same etiology of retardation.

The acquisition and expression of simple and complex meanings depend on children's semantic knowledge. Semantic knowledge, concept development, and the use of words to map concepts are linked closely in early development. Learning and use of simple noun referents is a progressive process in which children initially have a single example of a concept, which they mark using the referent word. For example, "cat" may refer at first to the child's particular stuffed cat. Next, the child may extend or overgeneralize the meaning of "cat" to include all stuffed animals and all furry four-legged animals found in the household environment. Eventually, the child's concept of "cat" and his use of the word are refined to correspond to the adult meaning and use of this word. The development of lexical knowledge continues with expansion of the number of words in the child's vocabulary and with more subtle refinement of meanings for those words.

Early semantic development also includes learning to express relational meanings using two or more words. For example, early two-word utterances typically include agent-action ("Daddy eat"), action-location ("Sit chair") and possession ("Chrissy bottle"). Development of the critical concepts of agent, action, object, location, and attribute depends on the child's ability to formulate categories based on his/her experience with the world. The categorization and conceptual development needed for generative use of word combinations are linked to the child's very early cognitive development.

Children with serious cognitive deficits often have difficulty acquiring the conceptual underpinnings of language use. They may acquire modest vocabularies, however, their meanings for words may be more restricted or different from adult meanings for these words. Children who have difficulty acquiring and expressing early semantic relationships (e.g., agent-action, action-location, action-object) usually are limited in their mastery of syntactic and morphological rules required for complex language in conversations. Use of syntax requires the formalization of the early social-relational meanings into a more complex linguistic representational system. While learning the basic representational structure of language as mapped by early semantic and lexical knowledge is necessary for the development of more complex and abstract rules that form the syntactic system, it is not sufficient. Because syntactic rules are numerous and vary in complexity, children with language disorders may master many rules yet still have obvious limits in their language skills.

Pragmatics is the set of rules governing the use of language to communicate meaning in the context of social interactions. The rules that underlie the pragmatic use of language reflect both social-cultural rules for interaction and the paralinguistic rules for modifying the nonverbal aspects of communication to enhance meaning. Pragmatic use of language develops from early nonverbal social interactions and builds on the expression of basic social intentions in communicative interaction. Early intentions, including requesting, greeting, commenting, and protesting, are first expressed nonverbally in the child's actions and gestures. Subsequently, single and multiple-word utterances are used to mark and elaborate the expression of social intention. Most languages are accompanied by a complex set of pragmatic rules related to the use of language in conversation. Acquisition of these rules for social communication in specific contexts begins in infancy and continues through adult life.

Because pragmatic knowledge is the basis for social communication, children who have limited verbal language skills still may be able to communicate basic social intentions effectively. Communication of social intention without a well-developed linguistic system, however, is dependent on the development of a signaling system that is shared by the child and those who interact with him/her. Child-caregiver interactions form the social-interactive basis for acquisition of early social communicative skills and for more complex language learning based in social meanings. Children who regularly interact with a responsive caregiver rapidly learn strategies for communicating with that person. At the same time, they develop the basic communicative skills that are necessary for communicating with unfamiliar persons.

FIG. 1.1. The interrelationships between the components and subcomponents of the language system and the potential impact of communication disorders on each aspect of children's language use.

Figure 1.1 contains a schematic represent...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Advances in School Psychology: An Overview of the Chapters

- 1. Alternative Intervention Strategies for the Treatment of Communication Disorders in Young Children with Developmental Disabilities

- 2. Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating a Preventative Intervention for High Risk Transfer Children

- 3. Sociometry, Temperament, and School Psychology

- 4. Preparation of School Psychologists in Behavioral Consultation Service Delivery

- 5. School Consultation to Support Students with Behavior Problems in Integrated Educational Programs

- Author Index

- Subject Index