- 231 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Industrial Geography of the Netherlands

About this book

This book, originally published in 1990, provides a comprehensive and detailed assessment of the Dutch economy since the war, discussing the changes which have been brought about by the restructuring of the economic base. The book employs case studies to analyse in particular the impact of regional policy, the position of the country in the international industrial network and the impact of large industrial concerns, foreign and domestic, on the Dutch economy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Industrial Geography of the Netherlands by Egbert Wever,Marc Smidt,Marc de Smidt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Naturwissenschaften & Geographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

1.1 Manufacturing and the Social Context

Industrial activities have almost always received a good deal of attention. Perhaps this is because modern industry provided the foundation for today’s pattern of urbanization. Indeed, the emergence of our cities is intertwined with the transition from traditional cottage industries to production in factories. It is also possible that the attention for industrial activities is brought about by the fact that they are usually highly concentrated in space. Through inertia, industrial estates and industrial zones maintain their reputation, if not their characteristic appearance, even if they lose their manufacturing function. A third possible factor may be found in the locational preferences of industrial firms. Modern industry in particular tends to be footloose and thus can exercise considerable freedom in selecting a location. Consequently, regional policy, which attempts to balance the distribution of both jobs and the labor force, was for a long time essentially industrialization policy. This explains why administrators and politicians focus on industrial firms in their attempt to draw businesses to their communities. A fourth factor could be the presence in the Netherlands of a number of corporations of international renown and importance. Among these are certainly Shell, Unilever and Philips, and probably firms like Hoogovens, AKZO, and Fokker.

Despite this attention, industrial activities are not always appreciated by society as a whole. The reconstruction period of the national economy after 1945 was a glorious era for Dutch industry. But this changed in the 1960s and 1970s. The continued economic expansion then brought a number of negative effects to light, certainly in specific regions: traffic congestion, degradation of the environment, insalubrious housing conditions, greater commuting distances, etc. There was increasing talk of selective growth and the necessity to alleviate the pressure on De Randstad as a reaction to these problems. For many it was clear that manufacturing was the culprit that caused these negative effects. Especially in the Randstad area, people thought they would be better off without industry. This negative attitude was fueled by the decline in the number of jobs in manufacturing after the mid-1960s, a consequence of rationalization and automation operations. At the same time the stature of the service sector was enhanced because it provided increasing numbers of jobs and it did not inflict visual damage on the environment.

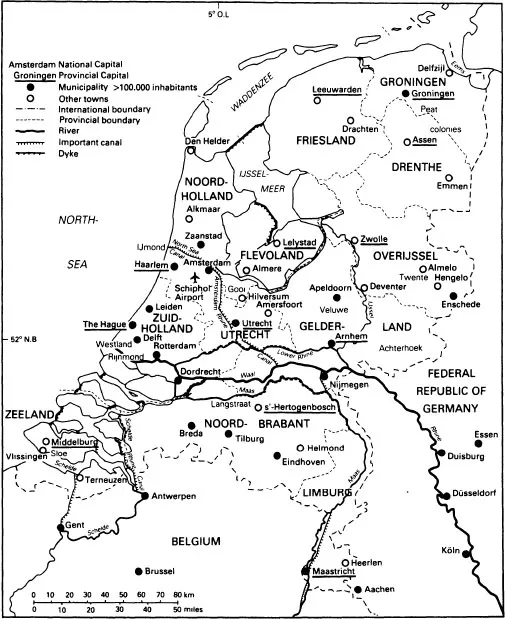

Fig. 1.1 The Netherlands: topography

By the end of the 1970s, however, the attention for manufacturing rose again, and with it came greater appreciation. Undoubtedly, this change is related to the economic recession. But another important factor was the publication of a report on the state and future of manufacturing in the Netherlands by the WRR, the scientific advisory board of the government. The report gave a gloomy picture of the strength of Dutch industry in the face of international competition. At the same time, it offered a number of suggestions for improvement. The report suggested that the only effective course of action would be to upgrade the industrial mix. The Netherlands should specialize in those products and sectors for which highly trained labor and specialized know-how are necessary. Obviously, such a change can only take place in the long term. Within a short span of time, industrial structures are rather inflexible, a fact to which many older industrial estates bear witness.

The activities of the Commission on the Progress of the Industrialization Policy (known as the ‘Wagner Commission’, after its chairman), which provided a follow-up to the report on the state and future of manufacturing in the Netherlands, further heightened the attention for industry. Concepts that were used frequently in the deliberations of this commission, such as ‘successful activities’, ‘high-tech activities’, ‘product and process innovations’ are mostly linked to industrial activities.

These developments in attitudes with regard to manufacturing provide the context for this study of manufacturing in the Netherlands. Industry has clearly lost much of the predominance it had in the economy of the early 1960s. But even today, it still comprises about 20 percent of the national labor volume. Its share in the total value added in the private sector is also roughly 20 percent. Its position with respect to investments in capital goods is somewhat weaker (15 percent), but manufactured products (including natural gas) account for a much more important share of total exports: well over 70 percent!

1.2 Manufacturing: Position, Distribution, Structure

Re-industrialization formed the basis for the reconstruction of the Dutch economy after 1945. In Chapter 2 the role and function of manufacturing in the reconstruction is discussed in detail. This discussion focuses on the industrialization debate that was carried on after 1945. The changing industrial structure and industrial policy are traced up to 1963, at which time the Netherlands appeared to be a mature industrial nation and the process of restructuring was initiated. The key position of manufacturing in reconstruction may seem surprising, in that the Netherlands was an industrial late bloomer. This warrants a brief treatment in Chapter 2 of the rise and development of manufacturing in the period prior to 1940. Although the emphasis is on the position of Dutch manufacturing within a wider societal context, some attention is also given to the distribution and the structure of industry.

Chapters 3 and 4 are closely related to Chapter 2. First, Chapter 3 treats the changes in the sectoral structure. Each period has its own particular sectors of growth and contraction. On the one hand, this is because consumer preferences change. The life cycle of manufactured products is brought up in this connection: for example, the replacement of black and white televisions by color sets. On the other hand, this is related to possible changes in international competitive positions. The expansion of certain industrial activities in one region or country can lead to contraction elsewhere. The rise of countries such as Japan and, later on, South Korea as shipbuilding nations and the dismantling of this sector in countries such as the Netherlands and Sweden is an example of this reciprocal relationship. Over time, this process generates strong fluctuations in the structure of industry. The dynamics of industry are discussed in depth in Chapter 3. After the successful industrialization after 1945, the international competitive position of Dutch industry weakened. The threat of de-industrialization provoked attempts to re-industrialize the economy. Re-industrialization was conceived as a way to make use of the country’s comparative advantages. This re-industrialization debate, in which Van der Zwan and Wagner took part, is also treated in Chapter 3.

Insight into sectoral dynamics is important for a thorough understanding of how the Dutch economy was built up and developed. Many growth and contraction activities are regionally concentrated. Classic examples are the leather goods and footwear industries in the area known as Langstraat in the province of Noord-Brabant and the textile industry in the region of Twente. Sectoral dynamics thus induce expansion and contraction and thereby often generate spatial dynamics. The distribution of industrial activity in the Netherlands is the central topic of Chapter 4. This discussion also deals with the importance of industry for the various regions. Since regional specializations tend to persist in the mental maps that people form of the Netherlands (e. g. the image of Twente and Langstraat), this chapter goes back to the period around 1930. At that time, the foundation was laid for a spatial pattern of specialization that was maintained for a long time afterwards.

The aspect of distribution is also the focus of Chapter 5, but in this case from the perspective of policy. Previous chapters dealt with industrialization policy at the national level, so this chapter concentrates on policy at the regional level. This regional policy, formulated at the end of the 1940s, is characterized by three essential changes. In the first place, it shifted from an almost exclusively industrial policy to one in which other economic sectors became increasingly important. Secondly, it moved away from incentives and toward development policy. In the third place, whereas policy had been the prerogative of government, a greater role was carved out for the regions to implement their own policy. Chapter 5 treats each of these shifts.

Fig. 1.2 The Netherlands: regions (COROP)

By definition, government policy is geared to a more or less distant future. Chapter 6 adopts that perspective as well. The steps toward renewal in industry and the opportunities for the future of various sectors are central to the discussion of the future. This chapter, which in many cases runs parallel to the activities of the ‘Wagner Commission’, elaborates on the distribution of high-potential activities in the context of innovative enterprise, innovative production environments and new business initiatives. This kind of information gives an indication of how Dutch industry will be distributed in the near future. The findings deviate somewhat from the commonly held spatial image of the Dutch economy. That image may be roughly characterized as De Randstad versus the rest of the Netherlands. The main thrust of this discussion of industry in the Netherlands is explicated most clearly in Chapter 6. The essence of the issues treated in this book may be summarized in terms of three processes: deconcentration, the dissolution of regional differentiation and the expansion of the Dutch urban field.

In each of the first six chapters, though most explicitly in Chapter 3, the open economy of the Netherlands is constantly in the background. This open character defines the constraints and the opportunities of the Dutch economy to such a high degree that it was deemed necessary to give this background extra attention. Chapter 7 therefore elaborates on the multinationalization of business and on the foreign firms that have located in the Netherlands. The aspects of position, distribution and structure are central to this discussion. Case studies are used to present the industrial developments around Schiphol and in the port of Rotterdam, which together form the core of the Netherlands’ international role as the ‘Gateway to Europe’. Chapter 8 deals with the largest Dutch manufacturing firms in terms of their origin, growth, restructuring and location.

Chapter 9, finally, summarizes the most salient findings. The concept of regional-economic potential provides a medium through which to explain the observation that spatial imagery no longer corresponds to spatial reality.

Throughout the book readers not well acquainted with the topography and toponomy of the Netherlands will encounter many names of cities, regions and provinces that may be unfamiliar to them. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 may help them place these names on a map.

2 The Industrialization Process in Perspective

2.1 The Need to Industrialize

In 1947, when the American Secretary of State Marshall addressed a group at Harvard on the necessity of launching a grand-scale European Recovery Program, the economy of the Netherlands was on the brink of collapse. In the two years since the end of the Second World War, work to repair the staggering war damage had hardly begun. Half of the domestic capital and 40 percent of the total production capacity had been lost. The energy and transportation infrastructures were in even worse shape. Food shortages undermined ‘our power to work’ which, according to Prime Minister Schermerhorn, ‘is virtually all we have left’ (Van der Linden 1985: 139). By 1947, the national reserve of dollars, which was being used to finance the import of goods to repair the war damage, was diminishing alarmingly, despite the liquidation of foreign assets. This depletion of reserves threatened to jeopardize the reconstruction of industry.

The problem of recovery and reconstruction was not a temporary one; the situation disclosed a number of structural problems. The problem that raised most concern was the employment situation. The memory of half a million unemployed at the trough of the Depression was still fresh In 1936, one-fifth of the labor force was unemployed, not to mention the immense number of underemployed.

The underlying problem was the position of the Netherlands as an industrial country, an issue that has not been fully resolved in the decades since the war. Attention for this issue was revived by the publication of a report on the present and future role of manufacturing in the Netherlands (WRR 1980). This does not make the early postwar experience less interesting. On the contrary, the debate on industrialization, carried on during the first decade after the Second World War, offers insight in the fundamental obstacles facing the country at that time. But in following chapters, the discussion of current industrialization problems will not only throw light on how the problems were previously resolved but will also clarify whether the issue of industrialization is still relevant. This presumes some understanding of the Netherlands as an industrial late bloomer, engaged until 1963 in adjusting to the European industrial pattern.

The Bleak Outlook in 1945

After 1945, industrial recovery and economic growth were not the only problems; population growth had become another important issue. Around 1937 the previously declining birthrate reversed; by 1946 the growth was a veritable explosion. In 1949, when the Dutch population reached the ten million mark, 60 percent of the respondents to a survey expressed deep concern about the consequences of the rapid population growth, such as unemployment, excessive population density, scarcity of food, and shortage of housing (Heeren 1985).

Employment had to be created for the vigorously growing labor force, primarily through industrialization, because agriculture was bound to shed labor. Emigration to countries such as Canada and Australia was seen as a recourse (annexation of German border areas was even considered as a way to augment agricultural production and resource exploitation!). The number of emigrants actually reached 48,690 in 1952. This way of easing the population pressure enjoyed strong governmental support.

Besides unemployment, the so-called external account...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 The Industrialization Process in Perspective

- Chapter 3 The International Perspective of Dutch Industry

- Chapter 4 Regional Industrial Patterns and Trends

- Chapter 5 Industrialization, Policy and The Region

- Chapter 6 Economic Revitalization and The Region

- Chapter 7 Corporate Internationalization: The Position of the Netherlands

- Chapter 8 Large Manufacturing Corporations in the Netherlands

- Chapter 9 Regional Development Potential

- Bibliographical References

- Index