![]()

Reform, Local Political Institutions and the Village Economy in China

Elisabeth J. Croll

Recent reforms in China have far-reaching implications for the form and content of village political and economic institutions and their relations with peasant households, family and kin groups. This article examines the recent separation of economic and political authority at the local level and the substitution of new township and village institutions for the commune, production brigade and production teams. With the development of the commodity economy and new economic associations, the government predicts a diminution in the production responsibility and autonomy of the newly emergent peasant household. However, a preliminary examination of the politics of the local economy suggest that peasant households may have developed alternative strategies based on new family forms and networks that potentially challenge village-wide political and economic structures.

In the past few years, one of the most important developments in many East European and Asian planned economies has been the introduction of new and radical rural economic reforms. These have separated political and economic authority, redefined responsibility for agricultural production and altered both the balance of production for the plan and the market and the balance of resource allocation between public and private forms. These reforms have far-reaching consequences for local political, social and economic institutions. In China it has been apparent since 1980 that such reforms have transformed not only the rural collective economy, but also the village social and political institutions that had encapsulated peasant households, families and kin groups since the late 1950s. Yet, although there has been much attention drawn by analysts of China to the economic repercussions of these recent reforms, less attention has been devoted to the far-reaching social and political implications that the reforms have for the form and content of village political and economic institutions and their relations with peasant households, family and kin groups.

One of the most important components of the recent reforms in rural China has been the separation at the local level of political and economic authority and the emergence of new political and economic institutions. Indeed, after the establishment of the production responsibility system, the local separation of political administration from economic management has been designated as the second most important of the economic reforms in rural areas. In the past five years, and since the introduction of the new constitution in late 1982, the government has reformed local political structures by substituting new township and village institutions for the commune, production brigade and production team, and redefining the scope of their authority and controls. The government has also established new forms of economic organization based on local corporations, co-operatives and economic associations, to expand production, develop the commodity economy and service economic enterprises managed by peasant households either individually or jointly.

As a result of these reforms, the government expects that within the village a new division of labour will emerge in which local political institutions remain in control of the local economy and are responsible for guiding, planning and managing its development, but where they no longer directly participate in production. Rather this is to be the responsibility of the individual household and co-operative or economic associations, which combine to make up a new two-tier system of local economic management. The individual peasant household will be responsible for the development of its own economy and the management of its own productive operations. The co-operative or economic association will manage production services and enterprises that are beyond the capacity of the individual peasant household. However, the government also expects that with increasing productivity in agriculture, diversification and specialization and the development of the commodity economy, co-operative forms of unified management will come to predominate over the individual household’s management of the local economy. A preliminary examination of new social, political and economic institutions in the villages suggests that such a hypothesis does not take sufficient account of the degree to which the peasant household has acquired a new measure of independence and control over inputs, resources and output; nor does it take into account the emergence of new family forms and strategies in the countryside whose networks may increasingly challenge the authority and controls of the new local economic and political structures.1

New Political Structures

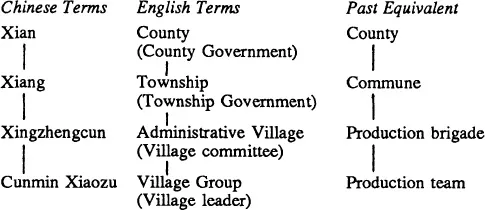

The reforms that separated political and economic authority and established new local political structures began in 1982 in accordance with the Draft Constitution of the People’s Republic of China. From the turn of the decade there had been some discussion about the form this restructuring should take and some experiments had been conducted in Sichuan province; but within a very brief period, in 1984, it was reported that the new political structures had been introduced throughout China (with the exception of Tibet). The new political structures below county level include the township, the administrative village and village groups, and each coincides with previous administrative divisions of and within the commune2 (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT STRUCTURES

The establishment of new township governments is the key to local restructuring and they have been set up to assume the government and administrative functions formerly vested in the commune. Thus township governments replaced the people’s commune governments which, originally introduced into China in 1958, combined economic and political authority over the means of production and were responsible for the production, management and operation of economic enterprises and of individual peasant households. Within the commune, the production brigade and production team, based on the whole or part of the rural village depending on its size, comprised the basic units of production with responsibility for accounting, planning and distribution. Between the state and the commune and within the commune, there was a single organizational structure, and China’s countryside was characterized by a clearly defined, hierarchical, single line of command combining political and economic authority. The collective structure, with its three tiers of commune, production brigade and production team, had almost entirely encapsulated the peasant household and the village economy, and the co-ordination of political and economic authority had meant that the peasant household had very little independence within or outside these structures.

Although historical forms of association and co-operation based on small kin relations and neighbourhood groups might have remained the focus of informal exchanges largely confined to ritual occasions, most of the traditional forms of family and kin-based co-operation had been formalized, enlarged and magnified by the process of collectivization to include all households within the productive unit.3 For instance, the process of collectivization had demanded that peasant households place a high value on the mobilization of collective resources and co-operate on unprecedented levels and in larger collective-wide activities. The incorporation of peasant households into these large village production units with exclusive control of resources and the means of production meant that, although their very solidarity might derive from and draw on kinship and neighbourhood ties, there was little institutional competition to the collective from the family, kin and village. In production, the peasant household had little or no access to alternative resources and inputs apart from those generated and distributed by the collective. However, it was the all-inclusive range of functions of the commune and its direct responsibility for production that were criticized by the reformers as an inefficient and institutional obstacle to rural economic development, and especially to the development of a commodity economy.

The new township government, unlike the communes, is responsible only for the administration of political and social affairs, and for administering overall government and county plans for the local economy. Under the direction of the township head and two executive heads, it has offices to manage markets, disaster-relief, public security, welfare, health, culture and education. Although the township government is charged with using economic, legal and other necessary administrative methods to guide and plan the economic development of the whole township, it is not charged with the administration of individual enterprises or organizing production by individual farmers. Indeed it is expressly prohibited from itself undertaking economic activities and from interfering in the specific production and management activities of individual and larger units of production. The township constitutes the lowest level of the formal local government administration hierarchy, and its officials, appointed and paid by the state, usually number some ten to 20 cadres. They are responsible for administering the affairs of the township and its constituent administrative villages.

An administrative village, like its forerunner, the production brigade, is an administrative subdivision covering a geographical area made up of one large or several small and natural villages, usually comprising a total of 200–400 households. Each administrative village is governed by a villagers’ committee, whose members are recommended or elected by the villagers and approved by the township office. It is not a formal part of the government administration, since the members of the village committee are not employees of the state, but are rather part-time local leaders. The constitution stipulates that the villagers’ committees are ‘mass organizations of self-management’4 which manage the public offices and social services of the village and help the local government in administration, production and construction. The village committee is usually made up of five persons, including the head or director of the village committee, two executive deputy directors, an accountant and a woman in charge of women’s affairs. Unlike the township and county, there is usually no division of personnel into branches. Instead, each person has multiple tasks and duties that might include the implementation of county or township policy, advising farmers on the development of their economic activities, taking charge of village construction work such as irrigation, forestry and roads, mediating in disputes, and overseeing the welfare of the poorest peasant households. Most of the members of the village committee expect to work one month a year on village affairs and they are usually paid 10–20 yuan a month to compensate for their loss of production time. This sum is paid from village committee funds which are managed by the village accountant and derive from either direct annual levies on member households, calculated according to household size, or proceeds from a portion of the village’s cultivated land set aside and cultivated on a sharecropping basis for this purpose. The village committee is responsible for co-ordinating the activities of its constituent village groups.

Each administrative village is divided into village groups with an average of 30–50 households and 100–150 persons in each. As for the former production team, whether the village group coincides with a natural village will very much depend on settlement patterns and the size of individual villages. Each village group has a village leader, who is elected or recommended by its constituent households, and it has access to the services of an accountant who may be responsible for the funds of one or several village groups. These two functionaries also receive a monthly sum, often six to nine yuan, contributed by the farmers to compensate for the loss of production time. The main functions of village group leaders are to acquaint villagers with government policy, to mediate in disputes, to be acquainted with the conditions of each member household in order to help them solve problems and advise them in the development of their incomes, and to disseminate information and technologies. The leader also arranges for each household to contribute labour for construction of village or township projects such as planting trees or developing roads, irrigation works or other community needs.

In rural China in the past five years these political reforms have been introduced and implemented so that the new local political structures continue to constitute a single line of political authority reaching from the county through to the township village and peasant household. Although these bodies have been redefined in name and function to exclude direct responsibilities for and participation in production, they are expected to control the development of the local economy. A recent report in People’s Daily on political power at the grass-roots level outlined the limits to the economic responsiblities of the local political organizations:

To guide and manage the economic work of the township is an important power bestowed on the township government by the law. The township government should use the economic, legal and necessary administrative methods to manage the economy of the whole township and serve the development of commodity production, but should not interfere in, undertake or even replace the specific production and management activities of economic organizations.5

In addition to and alongside this political restructuring and the establishment of new local political institutions, the government also advocates the establishment of new forms of economic organizations based on a two-tier system of management combining households with companies, associations or co-operatives.

New Economic Structures

When the first steps were taken to separate local political and economic authority, the reform was expressed largely in terms of simply ‘stripping’ the communes of their governmental and political functions and leaving them as economic entities responsible for organizing production of local enterprises, collectively owned and managed. Gradually, however, the economic role of the commune has declined as collectively managed enterprises were frequently contracted out to individuals or small groups of households and made responsible for their own profits and losses. The commune, instead of assuming new economic responsibilities in the wake of de-collectivization, has gradually diminished in importance so that the very use of the term has passed from the local rural vocabulary. Instead, government policy has increasingly directed attention towards a new twotiered system of economic management that combines individual management by the peasant household with co-operative and unified management of the larger services beyond the capacity of the individual household provided by local economic associations, corporations, compani...