![]()

Part I

Trial by jury and judicial reforms in Japan

Setting the scene

![]()

The context of the trial by jury1

Understanding the policy process requires a knowledge of the goals and perceptions of hundreds of actors throughout the country … when most of those actors are actively seeking to propagate their specific ‘spin’ on events.

(Paul A. Sabatier)2

Introduction

This first chapter will focus on Japan’s judicial policy after 1945. The political and social dynamics leading to the judicial reforms proposed in June 2001, and including the saiban’in 裁判員 system or mixed jury system, started decades earlier. On 12 June 2001, the report of the Justice System Reform Council (hereafter the Council or JSRC) was presented to Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō.3 Koizumi’s government swiftly decided to pay full attention to the reforms and to draft bills to realize the objectives listed in the JSRC’s report. The report was published online as well as all the minutes of the meetings leading up to the report in line with the main purpose of the judicial reforms, namely open justice for the people.4 The meetings started on 27 July 1999 and ended after 63 sessions on 12 June 2001. The Council called for, among other things, developing ADR (Alternative Dispute Resolution) and arbitration procedures as a way to resolve disputes efficiently, increasing the number of successful candidates to the legal profession, the establishment of specialized professional law schools, as well as more swift legal proceedings and an expansion of access to the courts. The report also proposed measures to ensure sufficient pluralism in the justice system, including the expansion of the pool from which judges would be nominated. The most mediatized reform that was proposed, however, was the introduction of popular participation in criminal trials. The mixed jury system, or saiban’in system as it was called, aimed to restore popular trust in the legal system more than any other aspect of legal reform. The lay judge system was presented as a new institution for the judiciary, foreign to the legal tradition but necessary to overcome the deficiencies of the criminal justice system in Japan. It was not mentioned in media and other reports announcing the mixed jury system – a form of the trial by jury where randomly selected citizens decide on facts and sentence jointly with a panel of professional judges – that Japan had previous experiences with the jury system.

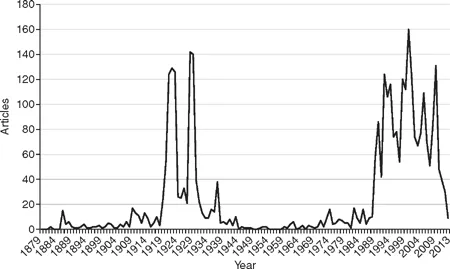

Politicians’ expectations of judicial reform were high and ambitious. In his policy speech in May 2001 Koizumi stated that ‘it is imperative that we reform our judicial system so that we can make the transition to an “after-the-fact check and relief society” based firmly on clearly established rules and the principles of self-responsibility’.5 The judicial reforms certainly fitted into a project of fundamentally reforming the paradigms of the Japanese state. This was considered to be the only possible way out of the deep socio-economic crisis that had haunted Japan since the beginning of the 1990s. The paradigm indeed shifted from what Daniel H. Foote labelled a ‘paternalistic state’6 towards Prime Minister Koizumi’s ‘after-the-fact check and relief society’. A few years after the publication of the report, media coverage on the judicial system in Japan suggested that the reforms were already resulting in tangible effects. Citizens were using the new opportunities to seize the courts in litigation even against the administration and thus turning into autonomous citizens conscious of their legal rights (Figure 1.1). Headlines in newspapers reflected this evolution: ‘Increasing Normative Consciousness’ (takamaru kihan ishiki 高まる規範意識) and ‘Expanding Responsibility and Increasing Litigation’ (hirogaru seki’nin, fueru teiso 広がる責任・増える提訴).7 The reforms that resulted from the suggestions by the Council were perceived by scholars and other analysts as major changes in the way in which legal institutions had been conceived and operated since the end of the Second World War.8 More than ten years after the publication of the report and several years after the implementation of the initiatives proposed, the results of the legal reforms are more mitigated. The success rate for the law schools is much lower than expected, and there has been no further increase in the number of administrative lawsuits.

Figure 1.1 Litigation rate in Japan per 10,000 people (1960–2013) (source: adapted from I. Ozaki (2013) ‘Law, Culture and Society in Modernizing Japan’, in D. Vanoverbeke, J. Maesschalck, D. Nelken and S. Parmentier, The Changing Role of Law in Japan: Empirical Studies in Culture, Society and Policy Making, Aldershot: Edward Elgar, p. 55).

The barriers that existed prior to the judicial reforms continue to hamper the effectiveness of the law and legal institutions in a country that is in dire need of repositioning itself as a major world economy. The judicial reforms are altering the paradigm of the role of law in a much less intrusive way than expected.

Before focusing on the problems related to implementation and effects of the judicial and law reforms, we should explain the exceptional fact that the majority of players involved in policy related to justice were able to reach an agreement in June 2001 on a far-reaching reshaping of the institutions of the judiciary in Japan. This was indeed a major achievement marking the outcome of a process that reached back in time and gradually built up towards change that permeated society as a whole. An explanation of the final outcome of interest for this book, namely the making, implementation and effect of the mixed jury system, first has to pass through a thorough analysis of the history of judicial policy in general and of the trial by jury in particular, as this will help us to explain why the actors in charge in contemporary Japan were able to take the decisions they took. The relevance of this story goes well beyond law in Japan. How can reforms take place in a conservative and closed policy-making system controlled by actors reluctant to grant access to new actors and novel ideas?

Policy-making concerning the administration of justice in postwar Japan had been dominated by discussion on the need to increase access to the courts and how to do so. Reforming the bar exam, unification of the legal profession, and reforming the Supreme Court to solve judicial backlogs were recurring themes in judicial policy-making. Although often demanded by various groups inside and outside the judiciary, reform on these themes had been incremental at best.

Yet, the reform of 2001 marks a spectacular punctuation in this otherwise incremental evolution. It was thorough and comprehensive, and the ‘first fundamental change since the Judicial Reform just after World War II’.9 Why did reform of the administration of justice finally happen then and not earlier? Ōta Shōzō suggests that this was caused by the advent of new actors in the policy venue in the 1990s.10 Before the 1990s, business leaders and the LDP had been quite indifferent to the judicial system, ‘since it has been totally irrelevant to Japan’s economy and policy-making’.11 When deregulation in the economic hardship of the 1990s engulfed Japan, the judiciary became relevant to the business world. This in turn resulted in the major business organizations and the LDP joining the policy venue for policy-making in the judicial field. It takes more than a few new actors joining the venue to explain reform. Changes in the public understanding of the policy or of the policy paradigm issue also play a crucial role in the radical departure from the past.12 The process of policy change is a complex process that gradually builds up from a situation of relative stability to drastic policy change.13

Public understanding depends on policy images that are described as widely accepted and generally supportive images of a policy that consists of a mixture of empirical information and emotive appeal.14 The dominant policy image before the reforms at the start of the twenty-first century was that informal dispute resolution better suits Japanese culture and that the number of lawyers may therefore remain limited. This reinforced policy-makers’ aim to perpetuate a stiff bar examination. It is useful to note that such stability is not absolute. There were occasional and incremental changes to slightly increase the number of successful candidates. Thus, even in a situation of equilibrium, communities of specialists are constantly dealing with issues and proposing alternatives to existing policy.

Several articles have been written on the policy process of legal reform in Japan. It was explained how policy-making in the field of judicial administration works. Yet, these studies typically look only at the 2001 reform and do not take into account the longer postwar developments and dynamics in which stability in the administration of justice was maintained. Most policy models are designed to explain stability or change. Stability and change are part of the same story and one cannot be explained without the other. The model we will propose encompasses both, and emphasizes two elements of the policy process: issue definition and agenda setting.15 We will explain how the administration of justice in Japan was defined in public discourse in different ways at different periods, and when and how issues related to the administration of justice rose and fell on the public agenda. This chapter therefore seeks to offer a model for explaining the overall dynamics in the process of judicial reform in Japan. The chapter consists of three main sections. First, we will describe the policy monopoly as a mutually reinforcing relationship between venue and image. Second, we will describe how initial attempts to reform justice administration in the fi...