![]()

PART I

Remembering Additive Logical Structures

In Part I (Chapters 1 to 6) we shall be looking at the remembrance of configurations or processes involving the most elementary logical structures: seriations, correspondences, and transitive and associative relations. These structures can be called additive, or, alternatively, linear, because they involve a single dimension. In Chapters 3 and 4 we shall be examining the correlation of two or three series with the help of a single criterion; the use of two criterea in multiplicative correlations (matrices) will be discussed in Chapters 7 and 8.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Remembering a Simple Serial Configuration1

In this chapter we shall examine the remembrance, after a lapse of (a) one week and (b) eight months, of a series of ten rods arranged without the child's assistance in (regularly) increasing order of size. This simple case will provide us with an excellent starting point, because we know a very great deal about most aspects of this structure, both as an operational schema and also as a 'good form'.

§1. The problem

In fact

(A) We know that such a series constitutes a 'good', simple and regular Gestalt, easily grasped both visually and intellectually;

(B) We have been familiar with the operation involved in seriation for some time, and there are many papers on the subject. Let us briefly recall the observable stages in the process (in the present experiment, the seriation of ten rods measuring from 9 to 16·2 cm presented to the child in a jumble):

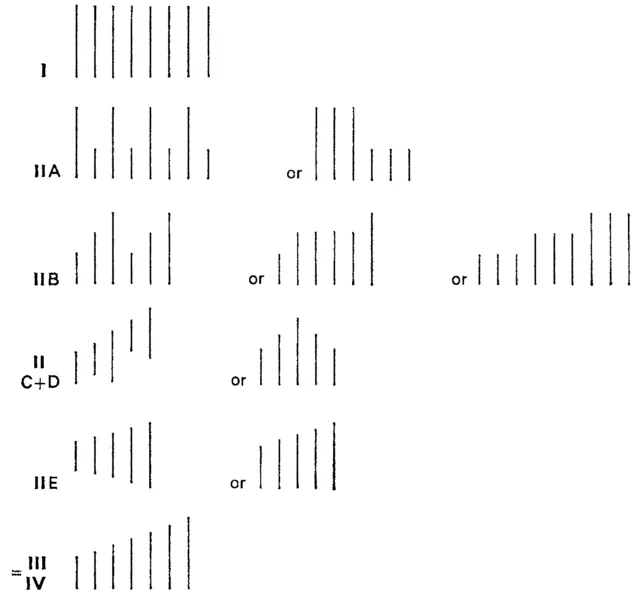

| Stage I: | No real attempt at ordination. |

| Stage II: | Failure to construct the over-ail series, but success in combining rods in terms of absolute qualities (bigness, smallness) or by pre-relations. |

| IIA: | Unco-ordinated pairs (pairs of large and small elements); |

| IIB: | Unco-ordinated triplets (one large, one medium-sized and one small element) etc.; |

| IIC: | Seriation based on the correct alignment of the tops of the rods but without a horizontal base; |

| IID: | 'Roof-shaped seriation: top profile rising and then descending (or vice versa); |

| IIE: | Correct seriation (by trial and error) of from three to six rods, but failure to go further. |

| Stage III: | Complete success (by trial and error), but if new (intermediate) elements are added, the subject does not fit them into place and generally prefers to reconstruct the entire series.2 |

| Stage IV: | Operational seriation, which has the following distinct characteristics : |

| 1. The subject proceeds systematically from the longest of all the rods to the longest among the remainder, etc. This involves double co-ordination: any element E is both such that E < F, G, and also such that E > D, C ... ; |

| 2. The inserted elements are immediately treated as terms of the series; |

| 3. The subject has grasped the meaning of transitivity: A < C if A < B and B < C. |

(C) Third, we know (and shall re-examine with the help of several subjects) that graphic reproductions of the series are in full accord with Luquet's findings about the drawing of seven- to eight-year-old subjects, far more like internal representations (Luquet's 'intellectual realism') than perceptions ('visual realism'). Now, it is clearly relevant to our problems that these reproductions, far from being random internal representations or reductions to a single or even to two types, should fit into levels that mirror the operational stages in the child's life, with correct drawings from about five years1 onwards (telescoping Stages III and IV, the latter having no sense in the case of drawings). There is the equivalent of Stage I in which all the rods are drawn as strokes of equal length. Then there are all the types associated with Stage II, slightly stylized or rather representing what the subject thinks he should be doing and not the objective lengths. Thus Stage IIA is represented by the alternation of large and small elements (pairs) but in such a way that all the large elements are equal and all the small ones as well, or else by a clear dichotomy between pairs or triplets of large and small rods of equal length; at Stages IIA, IIB and IIC there is a similar disregard of the fact that every rod is greater or smaller than any other (connexity).

Drawings of type IID, by contrast, introduce this property, as do those corresponding to Stages III-IV.

(D) Fourth, we are familiar with the anticipatory model of the seriation, thanks to the following experiment.2 Our subjects were presented with ten graduated sticks, each of a different colour, and asked to arrange them in order of increasing size, after first drawing what they thought the final arrangement would look like. The drawing was to be in black and white (general anticipation) or in the correct colours (analytical anticipation). Analytical anticipation is, of course, as difficult as the operational seriation itself, or even slightly harder (success at seven to eight years). Over-all anticipation, on the contrary, was found to be correct (horizontal base line, increasing lengths and connexity) in 55 per cent of our five-year-old subjects and in 73 per cent of our six-year-olds. This anticipatory model is therefore simpler than the operation (seven years)—drawing the correct series involves a one-way action, not reversibility (E > D, C, B, A; and E < F, G, H ...). The resulting model has a good perceptive form. It should also be noted that this model appears very soon after the first graphic reproductions, precisely because drawings are aids to perception.

(E) Lastly, thanks to the studies of one of our associates1 we have precise knowledge about the linguistic expression of the act of seriation. These studies have, in fact, shown that verbal descriptions of the seriation itself (that is, of the final configuration prepared in advance of the experiment and not of the reconstruction demanded for diagnostic purposes after the experiment) can be divided into four categories:

(1) Dichotomies: the only terms used are 'big' and 'small', whether the description involves such categories as a small one, a small one, a small one, a big one, a big one, etc., or whether it involves (purely mechanical) divisions into pairs (a small one, a big one; a small one, a big one, etc.).

(2) Trichotomies: and more detailed identifications: 'small, small, small; medium, medium, medium; big, big, big, etc.' or 'small, medium, big; small, medium, big, etc.'; or even 'very small, smallish, medium small, medium big', etc.

(3) One-way comparative descriptions: 'smallest, bigger, still bigger ... biggest'. When asked to describe the series the other way round, the child is baffled because the penultimate term ('still bigger') becomes 'smaller', and this calls for a grasp of relativity.

(4) Two-way comparative descriptions.

What is remarkable about these four categories is that they are in such close correspondence with the stages of operational development mentioned earlier. This is borne out by the following percentages obtained from tests with twenty-three subjects at Stage I (4;5—5;11), thirty-eight subjects at Stage II (4;5—5;8), fifty-four subjects at Stage III (4;4-6;5) and fifteen subjects at Stage IV (6;1-9;3):

| Linguistic category |

| Operational stage | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 1 | 91 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 26 | 63 | 11 | 0 |

| III | 2 | 59 | 24 | 15 |

| IV | 0 | 7 | 13 | 80 |

There is thus a clear correlation between language and operational level.

We can now go on to examine the remembrance of a serial configuration (a series of rods arranged in increasing order of size) and, in particular, to investigate whether the memory of that configuration, after a week or after several months, is based chiefly on the perceptive aspect of the series ('good form'); or on its operational aspect (pre-operational or operational schemata used in the construction of the series itself); or perhaps on various combinations of the two.

In fact, both aspects are more or less clearly involved in all recollections of the series, other than those based on pure perception (A) or pure operation (B). Graphic reproductions (C) quite obviously involve operational ability since, even though the model has been actually perceived, the drawings reflect the same stages as appear in the operational construction (B). Nevertheless, it is clear that perception plays an important part as well, because progress from stage to stage is accelerated and the correct picture is drawn at about the age of five years instead of at six or even seven to eight years, as it otherwise would have been. In the case of the anticipatory image (D), we find precisely the same development, though at a different pace. On the one hand, before the emergence of correct anticipations, we find the same stages as occur in object-drawing (and hence as in operational constructions): there is an accelerated development, though slightly less so than in the case of object-drawing, which means that operational schemata must be at work. On the other hand, correct over-all anticipation is attained without trial and error at the age of five-and-a-half to six years, and not at seven to eight, as happens in the operational construction of the series. It follows that the perceptive model based on the child's earlier and spontaneous experiences, or the 'good' Gestalt of the serial configuration, must have some influence on the child's reactions, for the mental image would not otherwise have been able to anticipate the configuration so precociously. Finally, in the case of language (E), the operational factor has become dominant.

With respect to the memory, therefore, the problem is to establish whether the perceptive influences which play so important a part in (C) and (D) also facilitate and accelerate the recall of a serial configuration at all ages or rather from a precocious age (five to six years) onwards, or whether the memory-image (five to six years) involved in recall follows the stages of the pre-operational and operational schemata. Unfortunately, we cannot draw up hypotheses based on the preceding data alone, and we apologize for our inability to offer a detailed hypothetical frame that can be directly confirmed, invalidated, or shown to be meaningless by experiments ... In fact, the child may have two distinct types of perception of the serial configuration he has been asked to memorize. On the one hand, he can look upon it as just another figure to be drawn from memory, as he would a circle, a square or a flight of stairs; on the other hand, the very fact that the ten rods are presented in order of increasing or decreasing length (according as the child first looks at the left or the right extremity) may cause him to see them as objects of possible manipulation or operation, particularly if he is told to describe them verbally (as in one of our techniques). In that case, the memory, as expressed in the drawing, will not bear on the purely figurative aspect of the model, but on what the child would have remembered had he constructed, or tried to construct, the series himself.

In fact, as we shall see, two hypotheses are verifiable—one, partly, when all prior analyses are omitted; the other, more fully, when the child is asked for a verbal description during the presentation of the series, and is therefore forced to have recourse to operational schemata.

§2. Methods

We have relied on two main methods (I and II), each with a subdivision (IA and IIA). In all of them, the subject is asked to look at a series, previously constructed, not for the purpose of getting him to repeat the construction but rather to determine how much of it he will remember after a week or several months.

We might, of course, have used other methods, based, for instance, on differences in recollection after direct perception of the experimental set-up, or after its construction or reconstruction (see Mental Imagery in the Child, Chapter 9). But then we should simply have r...