![]()

Part I

Theoretical foundations

![]()

Introduction

Feenberg (2002, 5) distinguishes between instrumental and substantive theories of technology. “The former treats technology as subservient to values established in other social spheres (e.g. politics or culture), while the latter attributes an autonomous cultural force to technology that overrides all traditional or competing values” (Feenberg 2002, 5). Instrumental theories consider technologies as neutral tools that serve the purposes of their users. Such tools are useful in any social context – “A hammer is a hammer”. In this view, technology is designed in a vacuum isolated from political ideologies. Instrumental notions give priority to the rational character of technology. Technology is comprehended as pure instrumentality being employed to achieve efficiency. This strictly functional approach is the dominant view of modern governments (Feenberg 2002, 5–6). In contrast, substantive theories deny the neutrality of technology and focus on the negative technological consequences for humanity and nature. Technology has become a whole way of life and is substantive to modern society. This view argues that technology and machinery are “overtaking” us and that there is no escape other than a retreat and return to tradition and simplicity. This apocalyptic vision often claims absurd, quasi-magical powers of technology and is best known through the writings of Ellul and Heidegger (Feenberg 2002, 6–8):

Despite their differences, instrumental and substantive theories share a ‘take it or leave it’ attitude toward technology. On the one hand, if technology is a mere instrumentality, indifferent to values, then its design is not at issue in political debate, only the range and efficiency of its application. On the other hand, if technology is the vehicle for a culture of domination, then we are condemned either to pursue its advance toward dystopia or to regress to a more primitive way of life. In neither case can we change it: in both theories, technology is destiny. Reason, in its technological form, is beyond human intervention or repair.

(Feenberg 2002, 8)

This chapter is inspired by these important findings and argues for the need for a third approach, a critical and dialectical theory of technology that understands the technological developments and dynamics as progressive and regressive, and entails a moment of techno-social change (Marcuse 1998, 2001; Bloch 1986; Feenberg 2002; Dyer-Witheford 1999; Fuchs 2008). I thus present some foundational concepts of a critical theory of media, technology, and society in the second section, continue with the dialectics of productive forces and relations of production in the third section, and conclude the chapter by describing the means of communication as means of production.

Foundational concepts of a critical theory of media,

technology, and society

A medium establishes and organizes a relation between two entities that generate information (Fuchs and Hofkirchner 2003, 209). Media enable and constrain information processes. Information is a subjective and objective process of cognition, communication, and cooperation. On an individual level, a subjective and cognitive structure characterizes system A (cognitive information process). On an intermediate level, occurring interaction between system A and system B provides an objective relation of communication (communicative information process). This communication process results in new information in system B (A to B) and may also be the other way round (B to A). It is determined that the information of system A has an effect on system B, but it is not exactly predestined what this effect looks like. On an integrational level, system A and system B are able to produce new combined information due to synergetic effects, which cannot be found on the individual or intermediate level (cooperative information process). Media exist in physical, biological, and social systems. Generally speaking, media provide objective relations of information between systems, but subjective effects play a major role. The existence of a medium is compulsory, but not a sufficient precondition for the self-organization of complex systems. Specifically speaking, societal media establish objective human relations and operate between living social actors where subjective interpretations and meanings are decisive. The existence of a societal medium is a compulsory precondition for communication, but understandings, responses, and constitutions of communication actors’ sense and meaning are not determined but relatively autonomous (Hofkirchner 2013, 184–196).

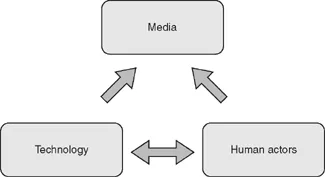

Material and ideal aspects characterize media (see Figure 1.1). For instance, computer-mediated communication such as the Internet incorporates both technological transmissions as well as content being produced by human actors.

Societal media are artefacts such as instruments, means, natural resources, property, power, and definitions mediating human relations and actions. That is to say, societal media are technologies that produce and organize information of interpersonal relations; hence, societal media are information technologies. Medium is a more abstract term than technology, because media exist in all self-organizing (physical, biological, and social) systems and technology is a certain characteristic of the social system (Fuchs and Hofkirchner 2003, 195–233).

Figure 1.1 Media, technology, and humans.

Originally, in the same meaning as “tekton”, which means builder or carpenter, the word “techne” had been constituted and become a philosophical concept in ancient Greek, before the term “technology” became generalized and familiar in modern societies (Kurrer 1990, 536). Technology may be understood as a purposeful unity of objects, means, methods, abilities, processes, and knowledge that are necessary in order to fulfil individual or social needs (Fuchs 2008, 47; Kurrer 1990, 535). That is to say, technology is a totality of objective and subjective factors and only objective aspects of technology are media (Fuchs and Hofkirchner 2003, 227). Technology is comprehended as a multifaceted unity in which the proper technics as certain methods adopt a subordinated position and are of secondary importance (Marcuse 1998, 41).

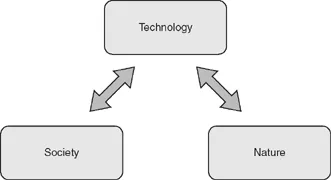

Technology mediates the relationship between human beings and nature (see Figure 1.2).

“Technology reveals the active relation of man to nature, the direct process of the production of his life, and thereby it also lays bare the process of the production of the social relations of his life, and of the mental conceptions that flow from those relations” (Marx 1976, 493, fn.4). Technology regulates the metabolism between the individual or a group of individuals (society) and nature (Hofkirchner 2002). Human actors make use of technology in order to adapt nature to society and to fulfil human needs. “Society . . . projects and undertakes the technological transformation of nature” (Marcuse 1972, 119) and “as technics expand their role in the reproduction of society, they establish an intermediate universe between Subject (methodical, transforming theory and practice) and Object (nature as the stuff, material of transformation)” (Marcuse 2001, 45). In the material and organic composition of capital, hence the relationship between means of production (natural and technological means of production) or constant capital (circulating and fixed capital) and labour power or variable capital; that is, through the means of production/labour power or c/v (Marx 1976, 762), we can identify the relationship between nature (constant circulating capital), technology (constant fixed capital), and human beings (variable capital) as well. In order to avoid the impression that society and technology act on the same level, it must be said that society is an upstream process and technology only exists because of society. The possibility that technology can also mediate the relationship between human actors and human knowledge/culture is treated in Chapter 7.

Figure 1.2 Technology, society, and nature.

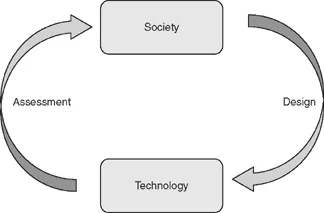

There is a mutual shaping of society and technology. Society constructs and shapes technology (design) on the one hand, and technology impacts upon and transforms society (assessment) on the other (see Figure 1.3).

The mutual relationship of society and technology is a dynamic process with shaping effects onto each other (Fuchs 2008, 2–3; Feenberg 2002, 48). Human beings are able to design and control the employment of technology and technology reacts upon society. Technology is therefore a subsystem of society.

Figure 1.3 Mutual shaping of society and technology.

Based on Giddens, Bourdieu, and Habermas, Fuchs (2008, 62) differentiates between the economic (disposition of resources), political (decision on regularities), and cultural (definition of rules) system as the core elements of society (see also Hofkirchner 2013, 241).

In order to survive, humans in society have to appropriate and change nature (ecology) with the help of technologies so that they can produce resources that they distribute and consume (economy), which enables them to make collective decisions (polity), form values, and acquire skills (culture).

(Fuchs 2008, 62, emphasis added)

In reference to the notion of the mutual relationship of society and technology, we may therefore argue that economic, political, and cultural processes shape technology and technology has in return an impact upon the economic, political, and cultural system. This includes that technological developments and the technological movement of the productive forces are not solely an economic process due to political and cultural impacts (Fuchs 2002, 323–324). Examples include the following:

• Governments and political groups previously regulated the sector of telecommunications to a certain degree.

• Privacy laws and data protection regulations constrain commercial web platforms to implement new technologies such as Google Street View and Facebook Beacon:

• Google Street View is a technology that providing panoramic views from positions along many streets around the world. Privacy advocates have pointed out that Google Street View shows people engaging in visible activities in which they do not wish to be seen publicly (e.g. men leaving strip clubs, protesters at an abortion clinic, and sunbathers in bikinis). The concerns have led to temporary stoppages of Street View in some countries.

• Beacon was part of Facebook’s advertisement system for the purpose of allowing targeted advertisements, which sent data from external websites to Facebook. After a class action lawsuit, Facebook had to shut down the service in September 2009.

The dynamics of technological progress additionally follow specific social norms and values. Cultural aspects also play an important role in the establishment of new technologies and technological innovations. For example:

• The open source community is an open access and open knowledge culture with cooperative production forms having developed the Linux operating system. It may be interpreted as a cultural expression of the discontent with proprietary commodities and the idea of the free distribution of digital knowledge.

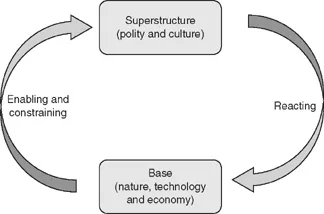

Technology is in capitalism medium and result of economic, political, and cultural processes, and is mutually mediated with antagonisms in economy, politics, and culture. Technology is the medium and outcome of these contradictions. Although the development of technology as a social process is the result of processes of negotiation and conflicts of interests between individuals, economic actors such as large corporations play a dominant role in this process, because available resources decide power dimensions extensively and intensively. One may argue that there is an asymmetrical relationship between economic, political, and cultural actors in the process of the technological movement of the productive forces with a predominant and powerful position of the economy. This insight goes hand in hand with Marxist notions about the dialectical relationship of base (nature, technology, and economy) and superstructure (polity and culture) (Williams 2005a; Hall 1986; Bhaskar 1998, 71–73; Holz 2005, 534; Fuchs 2008, 70) (see Figure 1.4).

The base is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of the superstructure and a complex and nonlinear reflection of the superstructure that trigger each other. Both the material base enables and constrains superstructural practices and the superstructure reacts upon basic structures. The dialectics of determination and indetermination shapes the relationship of base and superstructure. In addition, the superstructure is no mechanic effect or epiphenomenon of basic structures; the base is not an external force that mechanically determines superstructural actions. The superstructure may neither be deduced from nor reduced to the material base. A dialectical view on base and superstructure denies both economic reductionism and theoretical idealism. Polity and culture are simultaneously shaped by economic structures and open and interconnected practices having “relative indeterminacy” (Hall 1986, 43) and “relative autonomy” (Bhaskar 1998, 71).

Figure 1.4 Dialectical relationship of base and superstructure.

We have to revalue “determination” towards the setting of limits and the exertion of pressure, and away from a predicted, prefigured and controlled content. We have to revalue “superstructure” towards a related range of cultural practices, and away from a reflected, reproduced or specifically dependent content. And, crucially, we have to revalue “the base” away from the notion of a fixed economic or technological abstraction, and towards the specific activities of men in real social and economic relationships, containing fundamental contradictions and variations and therefore always in a state of dynamic process.

(Williams 2005a, 34)...