![]()

1 The persistence of form

The first point that needs to be clearly established is that the physical form of urban areas lasts a very long time. Dwellings may, typically, have a design life of 60 years or so but the reality is usually longer and this period is probably lengthening. In Europe, North America and many other parts of the world, dwellings constructed in the latter half of the nineteenth century are still in use today in large numbers. Some urban areas in Europe and the Americas contain significant urban fabric dating from the eighteenth century or even earlier. Refurbishment, repair and extension keep these buildings in use. They may change in use and intensity of use, but they retain their basic structure. Some commercial and industrial buildings may, indeed, have a design life of less than 50 years but there are also many others that are retained for very much longer. Some that have survived from the late nineteenth century, such as large textile mills, may now be retained in perpetuity even though their original use has vanished and may never return. Conservation polices, although comparatively recent arrivals in the historical context, show no sign of going out of fashion. As their influence becomes more and more significant, the point has now been reached where if a major building survives beyond its initially planned period of use, it is likely to be retained and conserved rather than be demolished. As new buildings of quality are constructed, so the absolute number of conserved structures will increase and, in some cases, the proportion of total buildings that is conserved may increase also.

The same arguments can be applied to transport infrastructure. Major roads may sometimes be widened out of all recognition but the historic line of route usually remains. Whereas urban motorways are clear examples of new construction that paid little or no heed to the existing patterns of urban form, they are rarely removed. Where this has happened, as for example in Portland, Oregon, Boston, Massachusetts, and San Francisco, California, in the US and Seoul in Korea, the policy has been to create public open space along the line of route rather than build over the space created, so retaining the original alignment. Similarly, although many of the urban areas created by nineteenth century industry may have lost the majority of their railways, those railway rights of way that survived into the late twentieth century show no signs of disappearing in the twenty-first. Whether converted to a recreational footpath, or where the railway has been retained and modernised, their routes remain an essential part of the contemporary city. Canals have proved even more difficult to remove. Birmingham in England is a notable example. Looking at the important recreational and amenity role played by its canal network nowadays it may be surprising to hear that it was the city council’s policy in the 1950s and 1960s to remove them as outdated industrial relics. However, it was discovered that they also formed an integral part of the city’s water supply system and their removal would have been impractical and costly. This is not just true for canals but also for docks and other port facilities. In port cities throughout the world, as new ports are created downstream or out of town, the old ones may be redeveloped for residential use but their waterways are rarely filled in.

Degrees of persistence

Academic studies that support these general observations can be found within the field of inquiry of urban morphology. The purpose of this book is not to describe this subject as such, as this is done very competently elsewhere, but to draw upon some of its insights into the historic evolution of urban form. In particular, studies in urban morphology have drawn attention to the persistence, that is, the survival over very long time periods, of particular aspects of urban form. Generally, town plans and street patterns exhibit a high degree of persistence both for the reasons set out above and also because the legal process of transfer of ownership tends to preserve the boundaries of a landholding long after the original use may have disappeared.

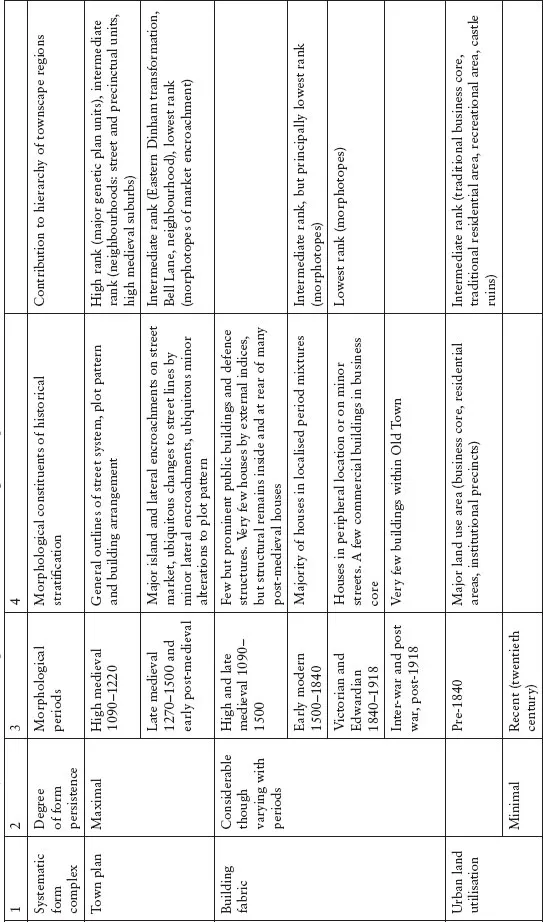

Within urban morphology, it is the work of Conzen that is of most relevance to the argument here. Not only did he develop his own conceptual structure within geography, drawing upon a German tradition going back to the latter part of the nineteenth century, but he carried out both academic research on town and country planning and was involved in planning practice. This diverse experience led eventually to his significant study of Alnwick, Northumberland (Conzen, 1960). In this book, Conzen analysed the historic development of the town plan of Alnwick from ancient times through to the mid-twentieth century. His conceptual structure focused upon buildings in their plots and how they were contained within streets and blocks. He observed that the rate of growth outwards from the historic core showed discontinuities over time resulting in the formation of fringe belts. Within these belts the built form displayed a morphological cohesion relating to the mode of origin although incorporating a variety of land uses. His analysis also permitted the recording and understanding of how, over time, types of urban form emerged from within a structure laid down by their predecessors. This process was often accompanied by the persistence of older boundary lines as a result of the constraints of the legal process of conveying land ownership. During the 1980s he developed his ideas further. By means of a study of Ludlow, Shropshire (Conzen, 1988), he refined his method, making more explicit the different degrees of persistence of town plan, building fabric and land use, which he termed systematic form complexes. His findings, shown by Table 1.1, were that the town plan, the outlines of the principal street system, plot pattern and building arrangements, had remained substantially unchanged over a 1000-year period. There had, of course, been more minor changes both to them and also to the building fabric in different periods but, even for the building fabric, a considerable proportion of it had been retained. On the other hand, he observed that land utilisation showed minimal persistence.

This brings us to an issue of terminology. Conzen refers to land utilisation by which is meant residential, business, recreation and similar uses. It is common in contemporary planning policy to use the term land use to represent a type of activity that is distinct from the land and structures that accommodates it. On the other hand, some structures are effectively defined by their use, notably transport facilities. A road or railway when no longer used is termed a disused road or disused railway; it does not lose its land-use name. To minimise any semantic confusion, this discussion will try to maintain a distinction between built form and the human activities associated with it. When the term land use is used it will also be in the sense of human activities such as living (residential), working (employment), recreation and so on, rather than the physical structures associated with them.

It is true that some areas of cities have undergone, and are still subject to, reconstruction that obliterates all records of the original form. Hausmann’s rebuilding of central Paris in the nineteenth century and the rebuilding in the 1960s of parts of city centres and inner-city areas in most developed countries, particularly those associated with housing renewal, are well-known examples. However, in both historic perspective and geographical extent, these events have proved uncommon, if only because of the financial and legal obstacles that have stood in their way. In some cases, where such comprehensive redevelopment has taken place, particularly in the reconstruction of central and inner-city areas during the 1960s, the later structures were subsequently demolished and elements of the original street pattern restored. For example, the Bullring in the centre of Birmingham in England was a nineteenth-century market on a site going back to far earlier times. In the early 1960s it was covered by a very large indoor shopping centre that obliterated all traces of the original street pattern. This was itself demolished in the late 1990s and the new shopping centre that replaced it restored the vistas along the lines of the original main roads.

It is also worth noting that public parks enjoy a very high level of persistence. This may seem a rather obvious point but it is nonetheless significant for it. The same is not, however, true of sports fields, including those owned by schools and universities (which are not strictly public if not entirely private) and these may often end up being redeveloped and built over.

Table 1.1 Conzen’s systematic form complexes for Ludlow with degrees of persistence

Source: Conzen, 1988.

If the physical form of towns and cities exhibits a high degree of persistence over time, what then does change? As Conzen observed, it is the land uses, in the sense of the human activities on and within the urban form. In general, land uses change at a faster rate than physical form. Not all land uses change but, where change occurs, it can be significant. Land-use change can occur across three, as well as two, dimensions. Witness the decline in the mid-twentieth century of residential accommodation above shops in high streets constructed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and its replacement by storage or offices. By the early twenty-first century, this trend had been reversed for new construction in numerous cities across the developed world as planning policies and market trends restored residential (and office) uses above shops.

How rapidly then do land uses change? Major changes in the economies of cities may work in long cycles of 50–100 years, or more, but much of office technology and retailing formats changes at a much faster rate, say 20–30 years. Changes in leisure pursuits occur within similar time periods. Not only do these elements of the urban economy change at this rate but so also do components of public policy. Ideas about the economic size and distribution of schools, primary and secondary health care, attitudes to provision for public transport and the motor car have all been subject to change over a few decades, a matter that will be considered in more detail in later chapters.

Implications for planning

There are some important lessons for planning here. Some observations that may, at first sight, appear very simple may, nevertheless, be shown to have profound implications. As built structures can be expected to last 60 years, and possibly remain in perpetuity, decisions on planning permission for individual buildings will have effects over a very long time period. Such decisions are sometimes seen as day-to-day matters affecting the now as opposed to development plan issues that are characterised as forward planning. However, all planning should necessarily be seen as forward by definition. Decisions on buildings are definitely long-term matters. On the other hand, development plans can be conceived as programmes for decision making, that is, they identify the decisions on development that need to be taken within the plan period. More commonly, though, a development plan conceives of the future state of an area at the end of the plan period, setting out how activities and physical form would fit together. Many would argue that it could hardly do otherwise.

The main point is, therefore, that physical form lasts a very long time, longer than the activities on it and within the buildings on it. Planning decisions need to take account of the ability of development to deal with changes over this long time period. It is often said that (and, indeed, has sometimes been said directly to the author by planning professionals) that ‘you don’t know what is going to happen’. The principal response to such a comment is that if this were literally true than planning would have no meaning and would be impossible to carry out. The real purpose of all planning (and not just town and country planning) is to deal with uncertainty by creating strategies that can provide for contingencies. However, somewhat ironically, the implication of the points made in this chapter is that, by and large, we do know what is going to happen. Most structures now extant will still be around in the future, as will nearly all of the new ones currently being granted permission. This will be the case despite changes in the particular activities associated with them and in society at large. Whether this situation is seen as desirable or not, the overall physical structure of urban areas will be with us for at least 60 years, and possibly indefinitely, and their design will be determined by decisions being made now. The planning decisions made now may influence future economic, demographic, social and cultural changes but they cannot determine them in the way that they determine physical form. For example, decisions on the quantity of office space are in reality more matters for now, or at most the medium term, whereas the decisions on the construction of office buildings are long-term ones.

Form as a constraint on activities

The next important point to be made is that, whereas urban form cannot positively determine human behaviour, it can make it either easy or difficult for people to carry out specific activities. In extreme circumstances, although a person’s physical surroundings cannot compel them to carry out a particular activity, such as playing in the park, travelling by train or driving a car, it can totally prevent them from doing so. If there is no park, railway or road then there are no facilities to be used and the activities cannot take place. Even when they do exist, barriers to movement can prevent people from accessing them. It is much easier to prevent than promote.

If, as we have noted, urban form is long lasting, and also expensive to change, its ability to help or hinder human activities is of central importance. When designing an urban area, the most important question should not be the nature of the buildings or facilities that people are currently demanding, nor whether or not changing public behaviour in a desired direction might be possible in the short term. Rather it should be a question, looking at the very long term, of what range of behaviours the urban form could easily facilitate and what range of behaviours that it should make difficult. Most importantly, it is the activities that are ruled out in the long term that need to be considered when framing the policies for today.

Numerous examples of this are available from the second half of the twentieth century, particularly the 1960s and 1970s. This historic period is always worthy of study because of the dramatic rebuilding and expansion of cities in Europe and North America during this period and the changes in public attitudes and policy that followed from it. A notable one is designing out crime. One does not need to go down the road of ‘better cities making better people’, criticised by Broady (1966) as ‘architectural determinism’. The defensible space argument of Oscar Newman (1972), the design principles of Responsive Environments (Bentley et al., 1985) and, subsequently, nearly all urban design texts from the mid-1980s onwards have embodied the idea that well-populated spaces with good surveillance, both within them and from adjacent buildings, permit the populace, to a large extent, to police themselves. On the other hand, spaces where people cannot be seen make it easy for criminals. In other words, the urban form does not control the propensity for criminality within the population but, rather, it provides a setting which, through its physical design, makes such activity either easier or more difficult.

Choice of mode of transport is another familiar example. The design of urban areas cannot, in itself, make a person drive a car, or use a bus or train, when they are free to do so. It can, however, make it very easy to use a car by providing parking space and appropriately designed roads, as is common, for example, in the North American outer suburb. It can also make it easy to run buses and trains efficiently by connecting development directly along rights of way for public transport. On the other hand, it can make it difficult to access areas by car by pedestrianising space and restricting car parking (or having no roads at all, as in the old city of Venice). It can also make it difficult to run buses profitably by creating extended cul-de-sac layouts and circuitous routes by road from place to place. The latter is a particularly pertinent example as it is something that is very difficult to change later, unlike pedestrianisation or provision of car parks.

A less well-trodden example is the disappearance of large backyards from new suburban houses in Australia from the 1990s onwards (Hall, 2010). There are important arguments for the provision of private open space around dwellings related to role of vegetation in drainage, microclimate, biodiversity and the energy use of dwellings as well as the more obvious ones of amenity and recreation. However, whatever position is taken on these issues, it is something that cannot now be changed without totally rebuilding all the post-1990s houses. Whatever the pros and cons, real or perceived, the change is effectively permanent and other options are ruled out. If you have a private garden, you do not have to use it. However, if you have no space for one, then there is no option.

All this would not be a problem if the physical form of urban areas was very easy to change or was in a constant state of flux of its own accord. However, as we have noted, its structure persists over very long time periods because it is difficult and expensive to change. The consequence is that it is what is ruled out that needs to be considered in the physical design of cities. If there is evidence at a certain point in time that a certain pattern of behaviour is desirable then the argument should not be about whether people could change in the short term. It should be about whether it would be facilitated in the long term and that the answer to this question should determine the design of future urban form. In other words, the design principle should be that the potential for the desirable behaviour must not be precluded in the long term.

Implications for residential density

In responding to the persistence of urban form generally, and the fact that different elements of form change at different rates, it is important to consider in more detail the matter of residential density. It is also important from a prescriptive policy standpoint, as planning policies often seek to restrict or promote changes in residential density, both up and down. We must note immediately that, in the final analysis, residential density is a matter of the number of people, as opposed to buildings or bed-spaces, per unit area. Some persons, such as tourists and family visitors, may be residing for a very short period. Permanent residents will be around for longer periods from a few years (much shorter t...