eBook - ePub

New Dynamics in Female Migration and Integration

- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Dynamics in Female Migration and Integration

About this book

This book explores the dynamic interplay between cross-national and cross-cultural patterns of female migration, integration and social change, by focusing on the specific case of Belgium. It provides insight into the dynamic interplay between gender and migration, and especially contributes to the knowledge of how migration changes gender relations in Belgium, as well as in the regions of origin. To this end, an analytical model for conducting gender-sensitive migration research is developed out of an initial theory-driven conceptual model. Employing a transversal approach, the researchers reveal similarities and differences across national backgrounds, disclosing the underlying, more "universal" gender dynamics.

Information

1 Gender-Sensitive Migration Research

Theory, Concepts and Methods

This chapter serves as the backbone of this book since it presents the theoretical and methodological framework of the project as a whole. While the gender ratio in contemporary migration flows is almost equal, the theoretical acknowledgement of this reality leaves so much to be desired. Despite increasing availability of literature on female migrants and female migration as a whole, findings are insufficiently leading to a theoretical reflection of the gender sensitivity of the migration process. After briefly addressing the current state of affairs on gender and migration, we develop our perspective on the way forward with regards to the theoretical developments in the field and we introduce an appropriate methodology and present our empirical focus.

1. The Feminization of Migration

The exponentially growing attention on women within migration studies during the last decade corresponds to the so-called feminization of migration. Women form an ever-growing part of international migratory flows (Kofman et al., 2000; Carling, 2005; Piper, 2005). However, this general tendency of feminization should be put into perspective. During the past two decades, the share of women in international migration flow hardly changed; between 1990 and 2010, it only fluctuated between 49% and 49.4% (United Nations, 2009). Also, in Europe, where women are more strongly represented among migrants than elsewhere in the world, female migration flow barely changed during this period, shifting from 52.7% in 1990 to 52.3% in 2010. On a broader scale however, a modest increase occurred where the proportion of women moved from 47% in 1960 to 51% in 2000 (United Nations, 2002). This tendency of feminization has nonetheless been partly neutralized by a drop to 49% in 2010 (United Nations, 2009).

While the general picture of migration appears to be rather gender balanced, it veils a far more complex reality. Indeed, a more detailed analysis according to regions and types of migration reveals a strong variation regarding the level of female migration. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, migration from post-Soviet countries to Belgium, for instance, has been mainly female-dominated, just like migration from Southeast Asia (Heyse et al., 2007). On the contrary, migration from other regions has a strong male character. The gender ratio also depends on the type of migration. Women tend to be overrepresented in family reunification migration (and more particularly in ‘marriage migration’), commercial migration in a marriage context (the so-called mail order brides), refugees, human trafficking and certain forms of labor migration (au pair or domestic workers, also termed ‘domestic services’) (Carling, 2005; Mahieu et al., 2009). The term ‘feminization’ not only refers to the quantitative presence of women in migration, but also to an assumable increase in female economic participation in international migration. During the 60s to 70s, and after the official migration stop in 1973, female migration to Europe consisted mainly of women who joined their migrated husbands in the context of bilateral employment agreements. Despite the long-term dominance of family-related migration motives, more recently women migrated more and more independently as labor migrants, students or refugees (Kofman et al., 2000).

The feminization of migration also relates to a growing visibility of women in migration studies. Although Ravenstein stated in 1885 that “females are more migratory than males”, women remained absent in most migration studies during the twentieth century (Lutz, 2010, 1647). Lutz also questioned the assumed ‘passive role’ of women in migration. The reference point in traditional migration research was a male labor migrant and the specific experiences of women were systematically disregarded (Lutz, 2010). The International Women Movement, feminists and academic scholars in women and gender studies have denounced this blind spot and emphasize that the assumed passive role of women coincides with the gender blindness of traditional migration research. This increased awareness has brought forth a research agenda with more attention on specific female migration and integration experiences (Mahieu et al., 2009). In other words, the growing visibility of female migrants is partly elicited by the feminization of migration research and the questioning of the gender sensitivity of traditional migration theories. This gradual entrance into a gender focus in migration studies is characterized by two key moments that coincide with two perspectives and developments within the gender and migration research fields. Since both perspectives are incorporated in the methodology of the FEMIGRIN project, we provide a short overview below.

2. The Female Perspective in Migration Research: From Attention on Women to Gender

Under the influence of the women movement and feminist studies, the number of case studies on female migration and integration has increased since the 70s. As a reaction to the invisibility of women in traditional migration research, women were added to the existing approach (Carling, 2005). In other words, the first correction on the male bias consisted of a mere addition of women (Pessar and Mahler, 2003). This ‘add women, mix and stir’ perspective contributed to the visibility of women in migration and to the insight that migration experiences differ for men and women (Carling, 2005; Piper, 2005). However, no attention was given to the relational character of gender and its structuring impact on migration patterns (Boyd and Grieco, 2003). In fact, reflection on the difference between male and female migrants did not surpass their sex difference. Moreover, studies on female migrants were often considered as a section of family or women’s studies and not as an innovative component of migration studies (Donato et al., 2006). As a result, the core theoretical assumptions and the research methods used were not questioned.

This growing attention to female migrants was the prelude for the development of a gender perspective in migration research. The term ‘gender’ refers to socially constructed definitions of masculinity and femininity (Van Roemburg and Spee, 2004; Mahler and Pessar, 2006). It constitutes the counterpart of ‘sex’, which refers merely to the biological difference between men and women. In contrast to sex, gender is context-depended, dynamic and relational. Along with the growing scholarly attention on women, the notion grew that not the biological differences between men and women, but the socioculturally defined meaning given to them offer an important explanative factor. Because gender is a fundamental organizational principle of society, it is essential in each discussion concerning the causes and consequences of international migration (DESA, 2006).

From an analytical perspective, gender relations influence migration at all levels (Grieco and Boyd, 1998). At the micro level, personal migration motives and decisions are influenced by gender roles and positions. Migration appears to be a way for women to escape gender-related abuse, such as domestic violence or gender-specific discrimination, like the repudiation of divorced women or widows (Morokvasic, 1991). In general, social restrictions on mobility and various types of social control are a push factor for women, not for men (Morokvasic, 1991). Gender relations also influence the opportunities for women to migrate. This becomes clear when scrutinizing the meso level, comprising of the migrants’ social networks. Social networks gain an ever-increasing importance in explaining migration, unquestionably in the light of globalization with increased mobility and information and communication possibilities. There exists a broad consensus that migrant networks of men and women differ and therefore contribute to divergent migration experiences (Curran and Saguy, 2001; Dannecker, 2005). At the macro level, a gender ideology penetrates all spheres of society (Donato et al., 2006). In this respect, the concept ‘gender order’ is useful. Gender order refers to the historically constructed patterns of power relations between men and women and to the established definitions of masculinity and femininity in a certain society (Connell, 1987: 98–99). This gender order also stipulates who is migrating and why, how decisions are made, what impact migration has on the migrants themselves and on the sending and receiving countries (Mahieu et al., 2009). Based on the above mentioned insights, there is an increasing recognition among migration scholars that the complete migration experience is a ‘gender’ phenomenon (Donato et al., 2006).

Despite the gradual recognition of the central role of gender in migration processes, the gender perspective hardly penetrates the core of migration theory (Kofman et al., 2000; Pessar and Mahler, 2003; Carling, 2005; Benhabib and Resnik, 2009). Many recent studies focus on detecting and changing the gender-blind migration policies and legislation (Stalford et al., 2009) rather than contributing to a gender-sensitive migration theory. While the body of literature on the topic is rapidly growing, there remains a need for theory-oriented study into the dynamic relation between gender and migration. Mahler and Pessar (2006) detect a methodological explanation for the lack of attention in the reciprocal influence between gender and migration in mainstream migration theory. While quantitative generalizing models remain a gold standard within migration research, the complex interplay between gender and migration requires a qualitative approach (Mahler and Pessar, 2006). In a research discipline dominated by quantitative methods, the strong prevalence of qualitative research methods in gender-sensitive migration studies continues to contribute to its nontheoretical character. In an attempt to overcome this impasse, we opted for a strong focus on theory development, underpinned by a well-conceived, balanced methodology. Our approach is explained in the following sections.

3. The Initial Conceptual Framework on Gender and Migration

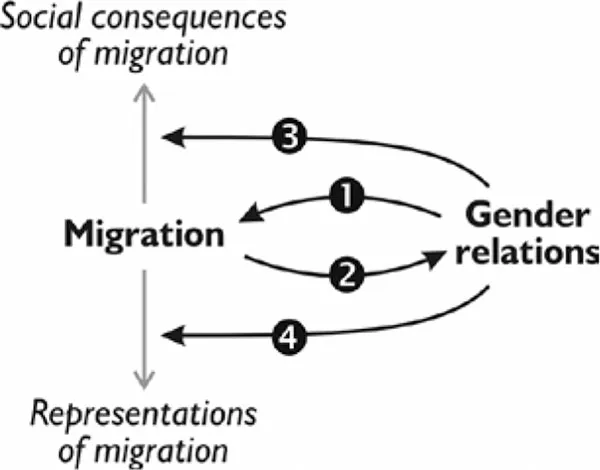

As previous research clearly demonstrates, gender is a factor of major importance at different levels (micro/meso/macro) and throughout the whole migration process. Moreover, the relationship between gender relations and migration is of a dynamic and reciprocal nature. In order to disentangle this complex relationship and enhance clarity on the distinct processes taking place, we designed a conceptual framework at the outset of the project (Figure 1.2). The model developed by Carling (2005) (Figure 1.1) on the reciprocal impact of gender on migration served as the starting point for the development of our conceptual model. Carling identified four different causal relations between gender and migration.

The first relation concerns the influence of gender relations on the size, direction and composition of migration flows and the perception of migrants. The second refers to the direct impact of migration on gender relations. The third covers how gender relations also define the wider social consequences of migration. Finally, the fourth relation shows how gender relations determine the representation of migration by academics, policy makers, the media and migrants themselves. In fact, we can split these four relations into two groups: (1) the influence of gender on migration (arrows 1, 3 and 4) and (2) the influence of migration on gender (arrow 2).

Figure 1.1 The reciprocal relation between gender relations and migration

Source: Carling (2005:5).

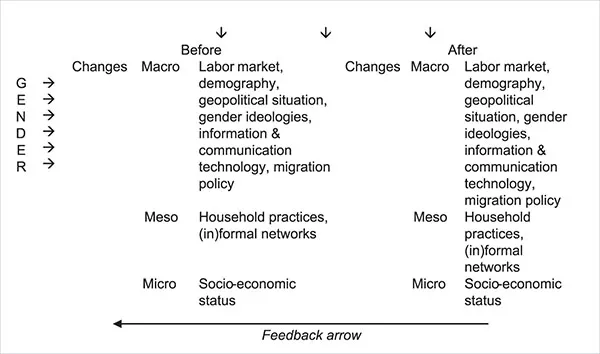

Figure 1.2 Initial conceptual framework of the FEMIGRIN study.

Source: CEMIS - CEDEM - HIVA - GERME

While Carling’s model is useful, we decided to refine it by adding an intermediate explanatory factor. We consider the sociological concept of ‘social change’ as the linking pin between gender relations and migration. Theories of social change are receptive for theorizing international migration (Castles, 2008; Portes, 2008) and explaining the relation between gender and migration (Curran and Saguy, 2001; Lutz, 2010). Global evolutions, such as economic globalization and new patterns of political and military power, change social relations worldwide. This overall social change develops along gender lines and generates gendered patterns of migration and integration. Migration and migration networks function as a catalyst for social change—particularly in gender relations—in both sending and receiving countries. To study the impact of migration on gender, we focus on gender-specific social transformations at different levels in the sending and receiving countries and analyze how these relational shifts relate to gender-specific migration and integration experiences. For the analysis of the variability of gender roles throughout the migration processes (the impact of gender on migration), we follow in the footsteps of studies that approach migration as a driving force for sociocultural change (e.g. Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2003; George, 2005; Parado and Flippen, 2005). Previous studies on the causal and reciprocal relationship between gender and migration are, however, far from univocal and strongly context-tied. Migration can both break and confirm existing gender roles (Foner, 2001; Piper, 2005; Timmerman, 2006). Moreover, the influence of migration on gender is exerted on several life domains and is seldom an ‘all-or-nothing’ issue. As such, migration can have, for example, an emancipating impact on gender relations within the family, but may create a downward mobility in the labor market. The impact of migration is, in other words, extremely complex and demands an analysis on several life domains at the same time. Therefore, we integrate several dimensions of gender and life domains such as the labor market, family, education and access to community-based resources and supplies in the conceptual model. Special attention is given to the role of migrant networks and to how these networks are structured by gender relations and self-modifying social relations.

Beside theories of social change, our initial conceptual framework was inspired by the model for gender-sensitive research developed by Grieco and Boyd (1998). According to these authors, gendered power relations influence migration processes at the macro, meso and micro levels, and all these levels, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- 1 Gender-Sensitive Migration Research: Theory, Concepts and Methods

- 2 Female Migration into Belgium

- 3 Migrant Women in the Labor Market

- 4 The Migration Trajectories of Russian and Ukrainian Women in Belgium

- 5 Female Filipino Migrants in Belgium: A Qualitative Analysis of Trends and Practices

- 6 Gender and Latin American Migration to Belgium

- 7 Migration of Romanian Women to Belgium: Strategies and Dynamics of the Migration Process

- 8 The Migration of Nigerian Women to Belgium: Qualitative Analysis of Trends and Dynamics

- 9 Explaining Female Migration and Integration Patterns: A Transversal Analysis

- Conclusion

- Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access New Dynamics in Female Migration and Integration by Christiane Timmerman,Marco Martiniello,Andrea Rea,Johan Wets in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.